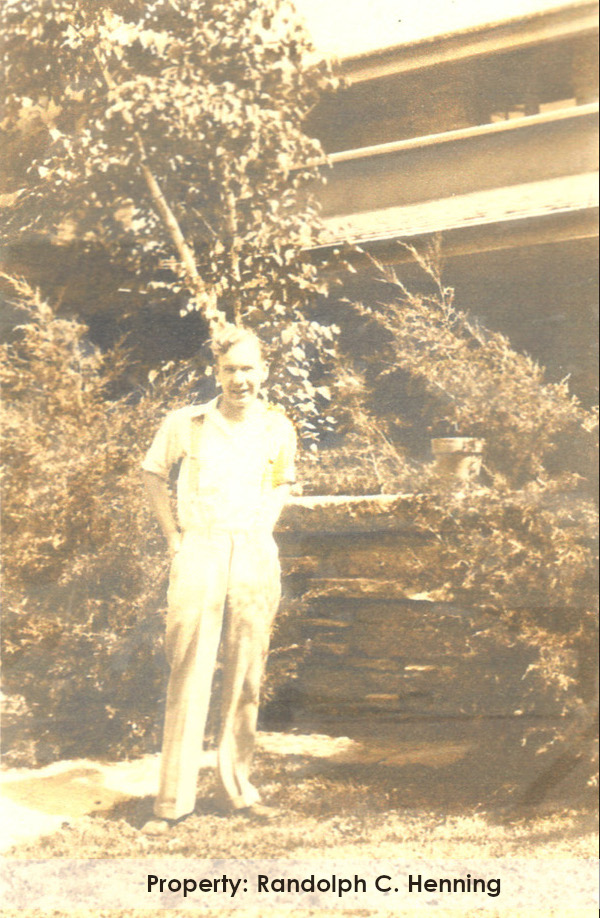

A photograph looking (plan) northeast at, apparently, Keith McCutcheon (1904-1968) in the Garden Court of Taliesin. The stone wall to his right was built while Wright reconstructed Taliesin after its second fire. Wright removed it in 1933.

Since we are close to Gay Pride Day, I thought I would write about: an employee of Frank Lloyd Wright’s who was gay; Wright’s nephew, Franklin Porter (1910-2002); and some letters.

Start at the start:

Years ago, I was trying to get the office printer to work in the office while I was the historian at Taliesin Preservation. I went to this dusty printer and found a bit of a mess around it. I needed to remove all of its surrounding debris to figure out how to get it printing.

Near the printer there was an in-out tray,1 which had pieces of paper, including all sorts of envelopes and folders. These things had been placed there by some members of the Preservation Crew. They had worked in the room for years, using it as a stable, warm place to write reports, track their hours, or get other things done.2

After I settled things with the printer, I decided to figure out what to do with all those pieces of paper.

I’m not a stickler for “a place for everything and everything in its place”, but it does help.

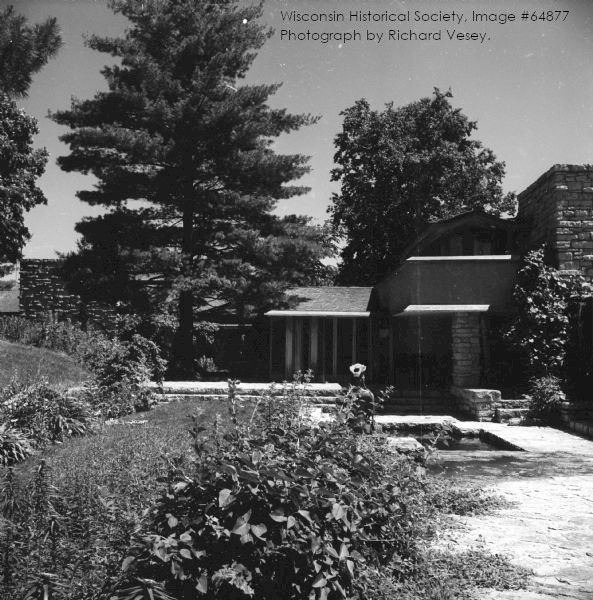

When I was done, I was left with a folder of things that belonged to Franklin Porter. Porter was the son of Jane and Andrew Porter. Jane Porter was Frank Lloyd Wright’s sister. Frank Lloyd Wright had designed Jane and Andrew’s house, Tan-y-Deri. “TYD” is across the hill from Taliesin. Below is a photograph that I took, looking from the edge of Taliesin’s Hill Crown toward Tan-y-Deri, which is under the arrow:

The story behind this:

The Preservation Crew found these things years before when working in one of Tan-y-Deri’s second-floor bedrooms. Frank Lloyd Wright purchased “TYD” in 1955 from his nephew, Franklin. The preservation at TYD started over 20 years ago. And, whenever there was money and time, the Preservation Crew restored/preserved/fixed it, and preservation managers at the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation worked on plans for the building’s complete restoration. Its restoration was complete in 2017. I took the photo of it, below, the next summer:

Along with

the plumbing, roofing, electricals and woodwork, the Preservation Crew fixed all of the interior plaster.

The man at the wall was the Taliesin Estate manager,3 and the photograph was taken by a member of the Preservation Crew. The crew took (and take) photographs constantly.

Pieces of paper fell down behind one of these walls. It seems these came from when Franklin Porter was probably in college. His parents lived near him where he went to college in Pennsylvania. But they kept Tan-y-Deri as a summer home. So, the Preservation Crew picked up these things while working at TYD and finally put them in the office.

To give you a sense of things:

One of the finds was a ski lift ticket:

p.s.: that picture above it not the actual ski ticket. I just put it in for “flavor”.

And a letter that Franklin’s mother, Jane Porter, sent her son telling him to bring his laundry home so she could wash it.

Plus three letters to Franklin from Keith McCutcheon.

McCutcheon was living not that far from Taliesin, in the village of Arena. He worked for Frank Lloyd Wright as a draftsman I think, starting in the late 1920s.

Keith met Franklin at Tan-y-Deri, after Jane Porter invited him over. It totally makes sense: Jane met Keith (working for her brother), and understood how out-of-the-way they all were (and are).

Keith wrote Franklin afterwards. And, based on what the two had said to each other that first evening, Keith suggested they write. In Keith’s first letter, dated September 5, 1932, he used a lot of adjectives. I got the real sense from the letter that Keith was smitten:

“[H]aving met so momently yet truly it most seemed I knew you – except the sound of voice, your size, and general mien…, Frankly, and I hope you like this candor, I’m rather fond of you – in truth, I like you….“

Keith expressed the desire to hear back from him.

I read the letters once or twice.

Then transcribed them4 and showed them later to my boyfriend. In essence, I said: “I don’t want to be judgmental, but doesn’t this sound like what someone would write to the person they were attracted to romantically?“

He agreed.

Keith sent poetry in the first letter, too:

This was a set of poems called, “Lyrics of the night: Poems of Passionate Weakness”. The first one is

“Taliesin: The home of Frank Lloyd Wright”:

I

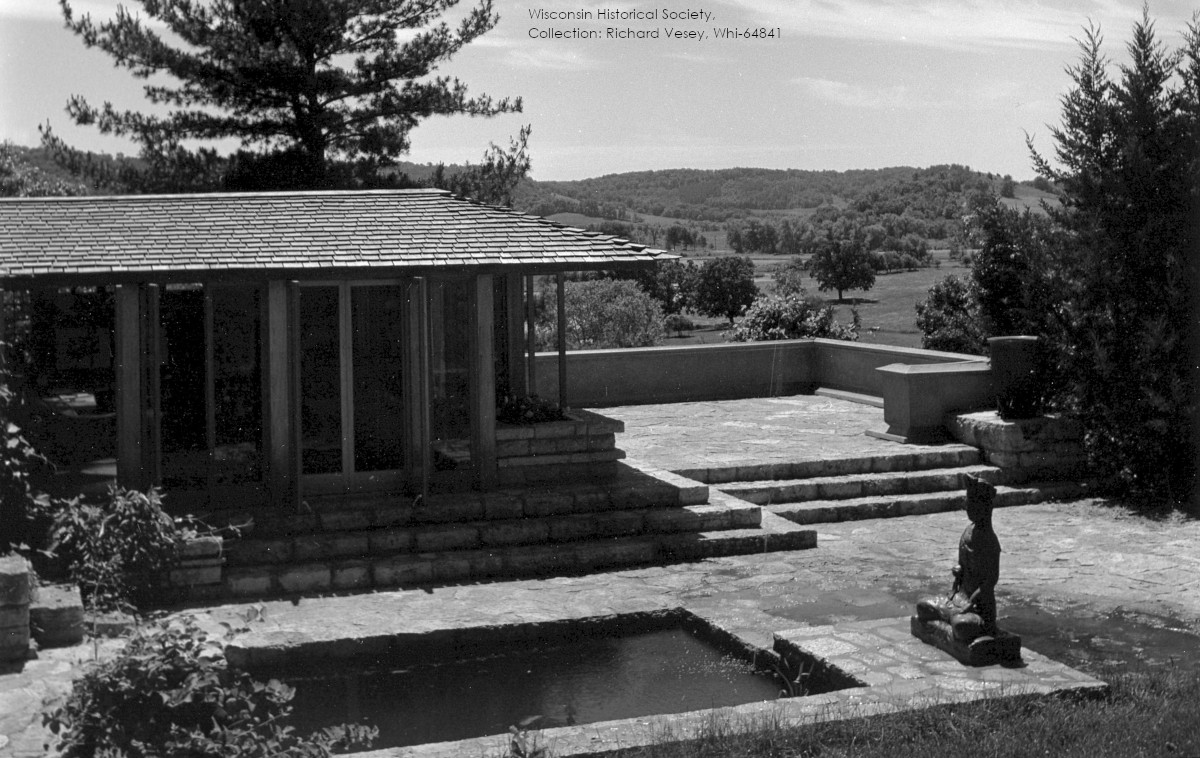

Upon a rounded crest of sun warmed hill,

Not far from the Wisconsin’s riffles’ gleam,

Reclines, in cat-like stealth, a house – a dream

Crouching along the ridge as if to fill

Itself among the rocks ‘tis made of: spill

Itself unnoticed midst the trees, and seem

More as a part of Nature’s own than scheme

Of cunning mind and power of man’s will.

A rambling residence that fills the heart

With far flung dreams, and vague desire. Hush

Of countryside is here; the spring-time lush:

Summer serene, and Autumn’s golden glow,

And then it’s blanketed beneath the snow –

Each season, Life reflected played its part . . .5

Franklin didn’t respond

I knew this because Keith began his second letter, written over a month later, with an apology for the first one. He characterizes that first letter to Franklin as his “moment’s madness”. And, while apologizing through the rest of the letter, Keith included another poem.

Keith sent his third, and last, letter in January 1933.

In it, Keith thanked Franklin for a Christmas card that Franklin had sent, and appreciates being remembered. And he extended well wishes to Franklin’s mother.

I didn’t really know what to do with what I had read, but I put them back in their folder and figured I would deal with them the next weekday that I was at work.

Here’s what stood out to me about this:

In small-town Wisconsin in the 1930s, a man (Keith) expressed an attraction to another man.

Keith got nowhere with it.

But I think it’s possible that—in small-town Wisconsin in the 1930s—had he wanted to, Franklin Porter could have sent a bunch of guys to Keith’s house to beat the hell out of him. But Franklin was kind enough (or cool enough) to not do that, and remembered to send Keith a Christmas card.

I did not know if the letters were overly flirty, of just expressed the desire for close male friendship. But, related or not, Keith McCutcheon was gay.

I know this because

after I did research for today’s post, I looked Keith McCutcheon up in Google. Through that, I came across this by Elisa Rolle. Rolle has been writing about gay people in small books. Her post on McCutcheon told me that McCutcheon settled in Madison, Wisconsin where he lived on the city’s “near east side” with his longtime partner, Joe Koberstein. The two are buried next to each other.

Additionally, Keith and Joe were mentioned in a write-up of We’ve Been Here All Along: Wisconsin’s Early Gay History, by R. Richard Wagner. “We’ve Been Here” was published in 2019.

A few days later:

I gave everything to the onsite collections manager for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation. Items from Tan-y-Deri aren’t directly connected to Frank Lloyd Wright, but the Foundation does own them, since they came from a building on the Taliesin estate. Tom (the collections manager) put everything into folders, separating them with acid-free paper. He then stored them with the other collections.

First published June 23, 2023.

The photograph of Keith McCutcheon at Taliesin is the property of Randolph C. Henning. Thanks to Henning for giving me permission to use it.

Notes:

1. oddly, while stackable trays are all over the internet, I can’t find any photos of “in-and-out” trays without stealing via a screengrab. There’s nothing at Wikipedia, or a website with free images. I really do not want Amazon.com on my a** just to get a photo of those hard, plastic, black trays. Who knew?

2. for those who work in the Hex Room at the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center: the tables in the room that end in bookcases are thanks to the Preservation Crew, who designed and built them.

3. That was Jim, who is in the article, “Wright Place, Wright Time“, by Andy Stoiber.

4. I transcribed it because it was such an unusual letter that I didn’t want to have problems recalling the letter later.

5. Thanks to Craig Jacobsen for sending me a copy of the poem.