Maynard Parker took the photo at the top of the post. It’s Taliesin’s Living Room and he took it 1955 for House Beautiful magazine’s issue devoted to Wright.

In this post I’ll be writing about the horizontal wood shelf in the center of the photo.

FWIW:

if I haven’t told you already, I’ve never tried to figure out why Frank Lloyd Wright made any changes at Taliesin.

Well: the fact that his house has a kitchen, bedrooms and bathrooms is self-explanatory…,

but I’m talking about experiments or changes. Like Wright adding the skylight in the “Little Kitchen” to show Solomon Guggenheim how the natural lighting at his museum would work.

Anyway,

For years, there was a door just to the left of where you entered the Living Room. It came out of the kitchen (known now as the “Little Kitchen”).

That door from the kitchen to the Living Room was there all the way back to the Taliesin I era (1911-1914). At that time the kitchen’s doors opened into the hallway and the living room.

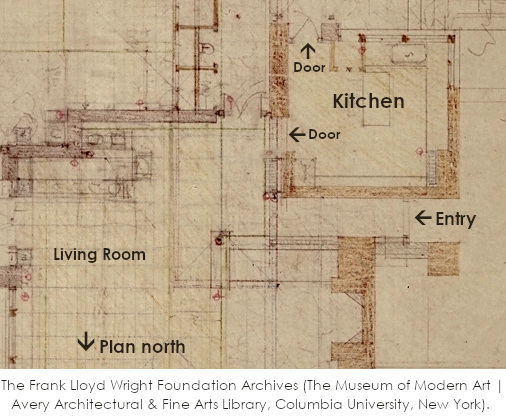

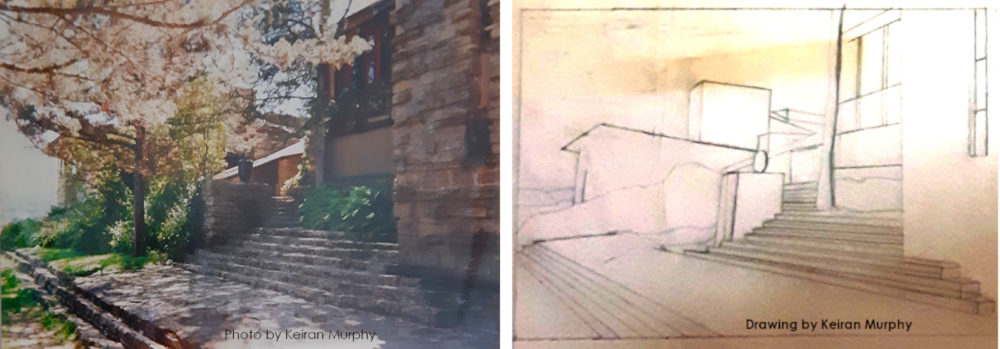

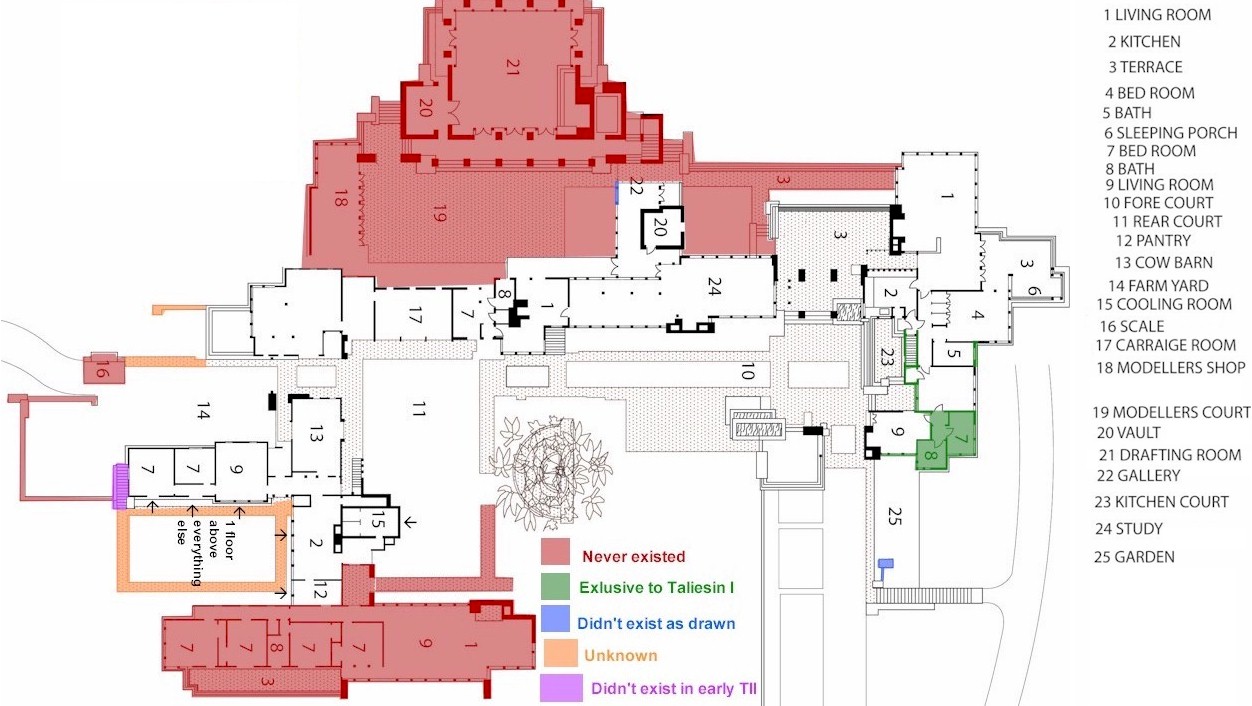

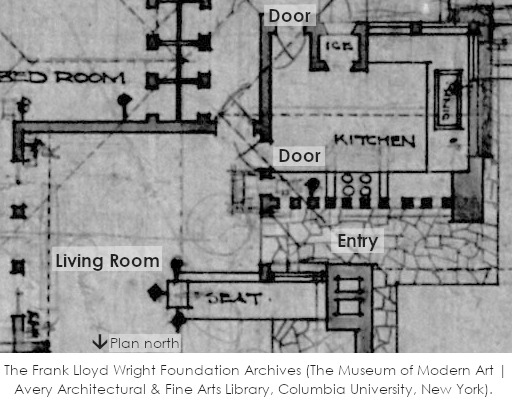

The drawing from 1911, below, shows the main entry, kitchen and Living Room. You can see where the doors were at that time:

Here’s another drawing from 1925 (after the second fire) to show you the same doorway:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, drawing #2501.001.

Then

In 1943, Wright got the commission for the Guggenheim Museum and then prepared for Guggenheim’s visit to Taliesin.1 Wright made many changes to Taliesin at that time. I’ve always thought that perhaps Wright made changes in order to entice the new client.

It might be part of the other changes Wright made in the early 1940s that I wrote about over a year ago.

But

these are slightly here I’m writing about different changes in this part of the room in the early 1940s.

These were changes related to the connection between the Little Kitchen and the Living Room.

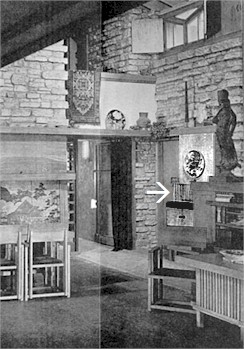

Here’s a photo with an arrow pointing at the door into the Little Kitchen.

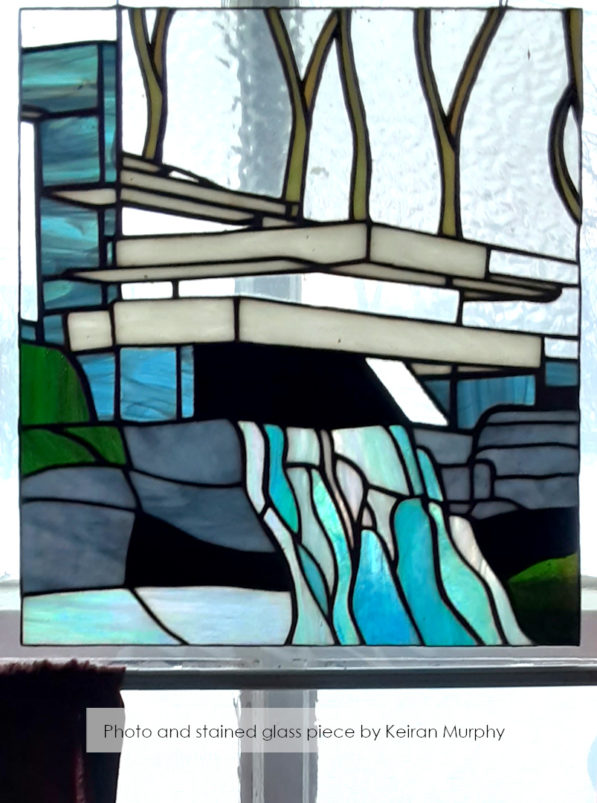

In the fall of 1937, Ken Hedrich (of Hedrich-Blessing photographers) took photos all over Taliesin and the Taliesin estate; while brother Bill took photos of that new Wright building designed over a waterfall.

In the fall of 1937, Ken Hedrich (of Hedrich-Blessing photographers) took photos all over Taliesin and the Taliesin estate; while brother Bill took photos of that new Wright building designed over a waterfall.

By the way: I always struggle to remember which Hedrich brother took photos at Taliesin (Ken) and which one took photos at Fallingwater (Bill). I almost think I should tattoo “Ken Hedrich took the Taliesin photos” on my arm…. Although today I had to look for the answer from my own blog (the post “Hillside Drafting Studio Flooring“)…. So I’ll just keep this website and blog going for… well until I’m in my late 90s at least.

Wright expanded the Little Kitchen in 1943. When that work was complete, the large door near the fireplace no longer went outside; it just opened into the kitchen.

Since he didn’t need the door Living Room any longer, Wright just had the apprentices veneer the original door with stone. They did a pretty good job matching, too. You wouldn’t really know it have been a door there unless you already knew.

Here’s a photo with stone where the door was, and the shelf in place:

After he removed the wooden door and veneered it with stone he put in the shelf you can see there. I have never seen a photo with the stone, but no shelf.

After he removed the wooden door and veneered it with stone he put in the shelf you can see there. I have never seen a photo with the stone, but no shelf.

While he might have just wanted that shelf there to draw your eye, or complete the design or match the trim on the south wall (that you see on the left-hand side of the photo).

But,

since a wooden door had been in the southwestern corner of the Living Room since 1925, the shelf under the bottom of the cabinet might really have been put there just to keep visitors from trying to exit the old way: the now non-existent door.

If you’d been a guest a few times at Taliesin, maybe you’d gotten used to getting a snack at night from the kitchen while staying in the Guest Bedroom? So, perhaps that shelf kept you from walking smack dab into a wall?

Now,

If you ever took a tour at Taliesin from 1994 until 2018, you walked into the Living Room and that corner was drywalled with gold paint on it. So the corner looked like what you see below:

The photo above is what that corner looked like when I first started working at Taliesin.2 And there were more rugs on the floor. That’s not original either. They’re rugs from the collection, but they weren’t there. Bruce Pfeiffer (former Wright apprentice and the original Curator of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Archives) used to say that many rugs in the Living Room made it look like an Asian rug shop. Well, former Wright apprentice John de Koven Hill was the one who “okayed” their location. Since “Johnny” joined the Taliesin Fellowship long before Bruce he outranked him, I guess.

Since the gold in that corner was determined not to be original to Wright’s lifetime, the drywall was removed. “Stilfehler” took a photograph of the corner on a tour and loaded it onto Wikimedia Commons:

First published August 26, 2023.

The photograph at the top of this post is also in the Maynard Parker collection at the Huntington Library. It’s online here.

Notes:

1. I thought for years that Wright did all these changes in anticipation of Guggenheim’s visit. You would, too, if you’ve read Working With Mr. Wright: What It Was Like, by Curtis Besinger. But in 2012, the diary of Priscilla Henken was published. This was a daily diary that Henken wrote in from October 1942 to late August 1943. On page 195 of the diary, July 18, 1943, Henken wrote that the Wrights, who had been away for days from Taliesin, were back and that: “The contract is for a million dollar museum for non-objective art, sponsored by Solomon Guggenheim….” So: that changed things.

2. By the way: the photo shows the very end of the inglenook in the Living Room (it’s under the metal Asian statue). That’s got gold, too. Was that original? Yes it was. And I’ve been told it’s gold leaf.