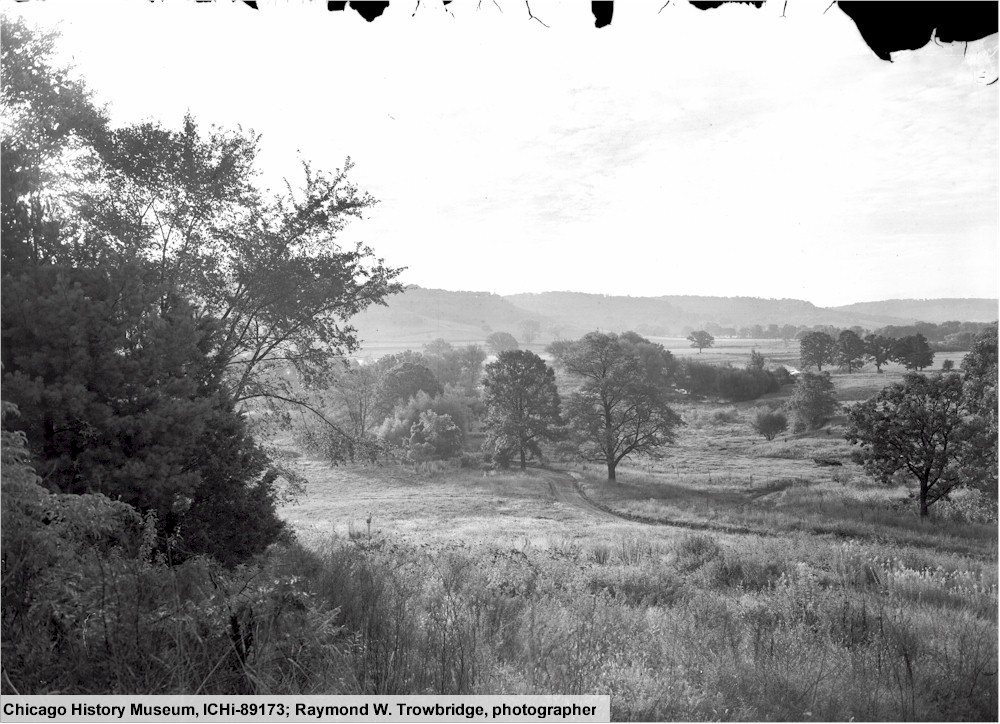

This photo was taken in 1930. The photograph was looking south (with the Taliesin structure behind the photographer and to the left). I picked this photo because it shows the beauty of the valley in which Taliesin stands.

I’m going to write about The Valley and Native Americans today because native people’s do have a history in the area, and we’re coming upon Columbus Day / Indigenous Peoples’ Day.1

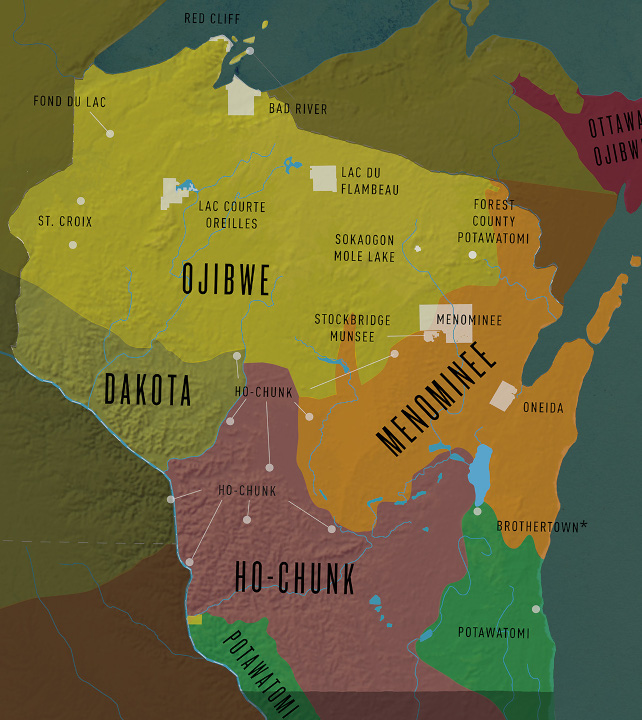

While there was never a village or long-term settlement of Native American people in the Lloyd Jones Valley itself, evidence shows they used the valley. And the map below shows which people were in Wisconsin, and southwest Wisconsin where Frank Lloyd Wright lived.

Native Americans in Wisconsin

To put things in context with Wright/Taliesin, I’m going to write a little about the Indigenous people in Wisconsin.

They began arriving

in what becomes the state of Wisconsin beginning 12,000 years ago at the end of the last Ice Age. Migration concentrated around the Great Lakes.

The Great Lakes:

Here’s mnemonic device to remember their names:

H uron

O ntario

M ichigan

E rie

S uperior

Settlement in the rest of Wisconsin didn’t start until at least 1,500 BCE. That’s because, while the Ice Age had ended, the retreat of the glaciers left some of Wisconsin an “uninhabitable bog.”

Patty Loew, Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal (Wisconsin Historical Society Press, Madison, 2001), 2.

Wisconsin tribes:

The North and West settlers were the Dakota and Ho-Chunk (formerly known as the Winnebago).

“Winnebago” is the transliteration from the Mesquakie (or Fox Nation) word, Ouinipegouek, which means “people of the stinking water.” This was not meant as an insult; it looks like it was a mistake.

Patty Loew, Indian Nations of Wisconsin, 40.

But, yeah, no thanks. “Ho-Chunk” is their language and means, “The people of the big voice” or “people of the sacred language.”

Settlers in Northeast, Central and South Wisconsin were the Menominee, Ojibwe and Potawatomi.

Patty Loew, Indian Nations of Wisconsin, 8.

Back to the Valley, near the Wisconsin River

A bend at the river brought hunters. That’s because where the river bends by Taliesin today, the water is deeper. So, it stays unfrozen most of the winter.

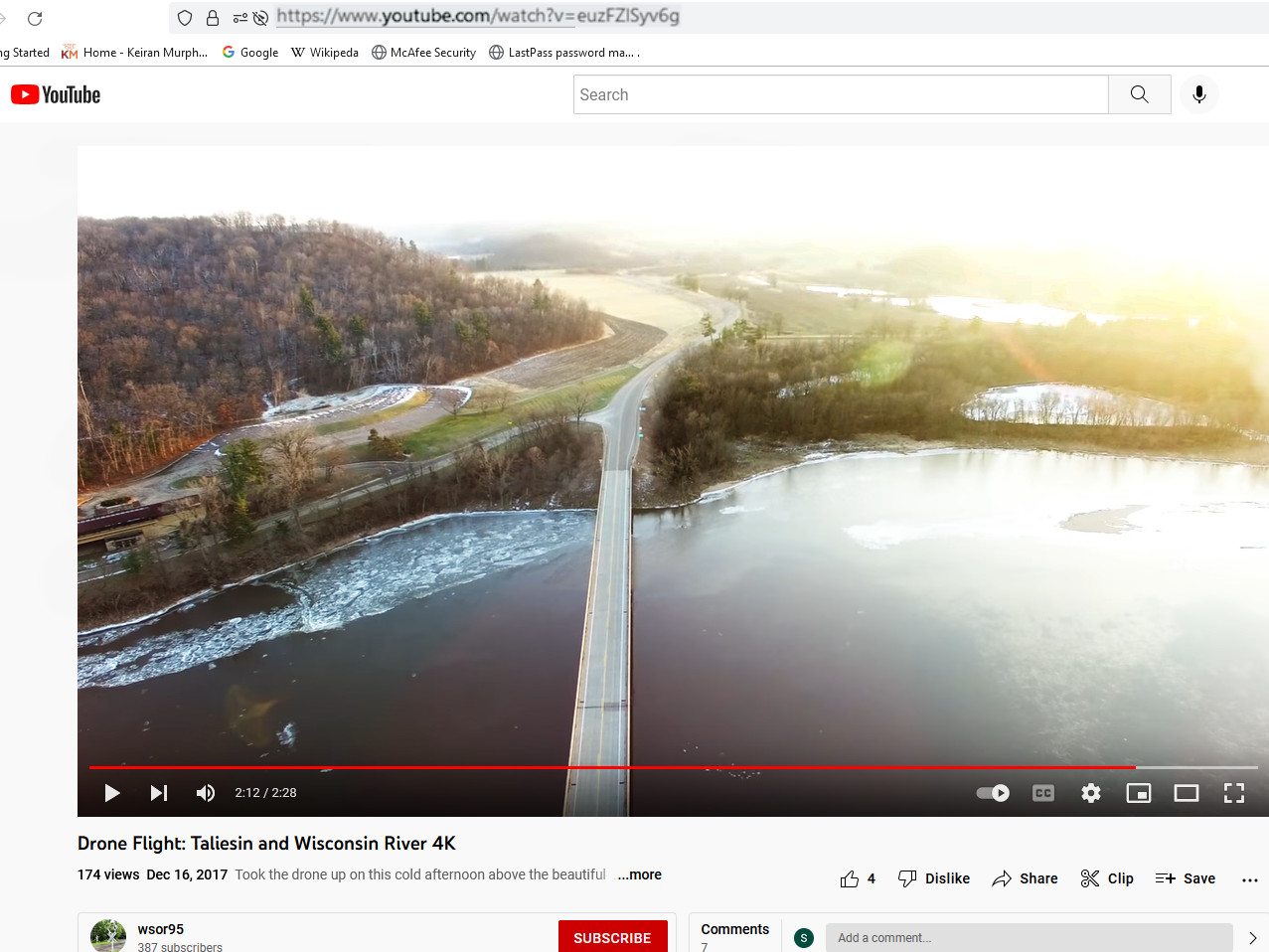

Check out the bend in the drone image below:

Screenshot from a drone flight by “wsor95“. Looking south over to the Taliesin estate. The edge of the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center is on the left-hand side of the photograph. To the left and right of the bridge is the bend where the Wisconsin River remains liquid through most of the winter (even when the temperatures in Wisconsin can get to negative 40 degrees2).

Since the water stays unfrozen, both hunters and birds could fish. And the hunters could catch birds who came for the fish.3

Other signs of Indigenous people

Native people also made effigy mounds in Southwestern Wisconsin, like at Governor Dodge State Park which is about a 15-minute drive away from The Valley. Construction on effigy mounds throughout the state began around 500 BCE.

Patty Loew, Indian Nations of Wisconsin, 6.

Indigenous and European cultures first interacted with each other due to United States citizens settling the area and (mostly) French fur traders.

This began to rearrange settlement areas in Wisconsin—different groups of indigenous people moved to different areas in order to live unmolested.

Skirmishes occurred over the three groups: settlers, Fox, and Sauk;

fortunately these conflicts mostly bypassed the Ho-Chunk, but lead to their diminishment.

Southwestern Wisconsin

Then, in 1821, lead ore was discovered in Southwestern Wisconsin. This, and other things, eventually led to “the Winnebago War” of 1827 and, more importantly (due to reasons other than the lead ore),

The Black Hawk War

This was in 1832 and things happened close to The Valley.

Here’s what the historic sign says on the edge of the drive into the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center parking lot:.

In this vicinity, during the Black Hawk War of 1832, General Henry Atkinson and approximately 1,000 soldiers crossed the Wisconsin River in pursuit of Sac [sic] Indian leader Black Hawk and his followers. On July 26th, at the old abandoned Village of Helena, the soldiers dismantled the village’s buildings to make rafts for the crossing.

Treaty of 1837

Many people moved west across the Mississippi River, but some would return. The return of “non-treaty abiding” Ho-Chunk were followed by removals on:

“four more occasions between 1844 and 1873”

which (due to public disapproval of the harsh removal of Ho-Chunk in 1873) until it led to a provision in the Homestead Act that:

“any adult head of a [Ho-Chunk] family could file a claim for federally-owned land, make minimal improvements, and, after five years, own it.“

Many a Fine Harvest: Sauk County, 1840-1990, by Michael J. Goc, 15.

During this time (1863), the Lloyd Joneses came in.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s sister, Maginel Wright Enright, wrote about this in her book, The Valley of the God-Almighty Joneses. I’ll end this with her words. They’re the most personal remembrances of Indigenous People in the Valley:

…. When [her grandfather] Richard and his family had first reached the wilderness, the Indians [sic] were formidable, mysterious; … still masters of the forest then. In the winter, when it was very cold… Richard and [grandmother] Mallie and whoever was sleeping in the trundle bed would wake to the click of the door latch. They would lie still… knowing that it was an Indian come to lie awhile by the fire and warm himself. In the morning there was no trace of the guest. That evening, or the next day, they could find a haunch of venison or a bag of meal or nuts on the doorstep as payment for the night’s lodging.

In the summers, when Richard worked out of doors, the Indians watched him from the silence of the forest. They watched and waited; they did not make hasty judgments.

But now they watched and waited in pathetic little bands over the land that had once been their home and hunting grounds, before men came to civilize it. They were lost and bitter, and farm animals disappeared when they were near, especially when they’d got hold of some liquor. Richard still tried to be friendly to them; he understood their tragedy, how it must feel to have the earth they loved taken from them. Perhaps he felt a little guilty for being one of the takers.

…

Another time when Richard and the boys were rushing to get the wheat crop under cover before a storm broke, a group of thirty Indians came through the field. They saw what was happening, and without a word began to help. When the last load was safely in the barn they went away, and the storm broke….

[A]t first, when [the Indians] were driven away, it had not seemed a final thing. Then, gradually, they sensed the enormity of what was happening to this land that the intruders had named America. They learned their lesson, admitted defeat, and did not come back.

Maginel Wright Barney, The Valley of the God-Almighty Joneses: Reminiscences of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Sister (Appleton-Century, New York, 1965), 55-56.

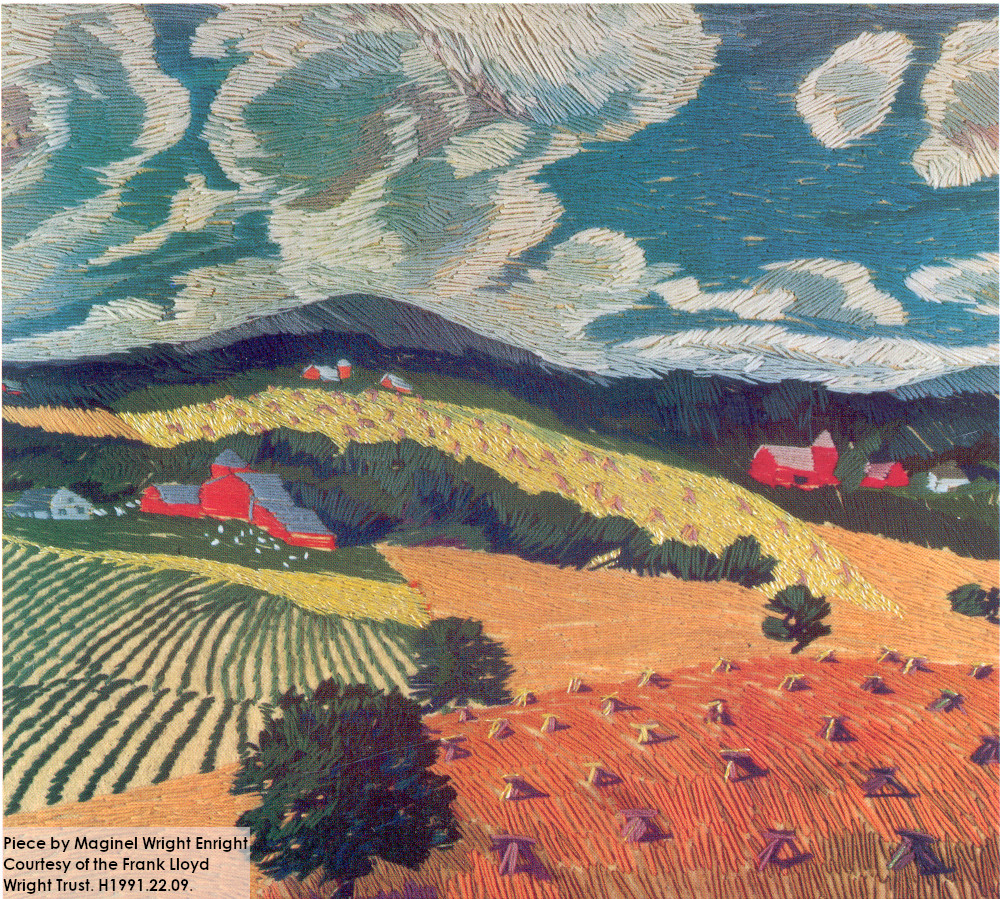

Here’s a piece by Maginel that recalls landscape paintings of the local area.

Thanks to Kyle Dockery, Collections Coordinator for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation, for helping me to correctly identify the owner of this piece by Maginel.

First published October 3, 2022.

The photograph at the top of this post is Chicago History Museum, ICHi-89173, Raymond W. Trowbridge, photographer. It is in the public domain. Here’s where you can see the image at the Chicago History Museum website. My post about Raymond Trowbridge (with more photos) is here.

Notes:

1 I’m not a historian of indigenous people. I gathered this information from Indian Nations of Wisconsin: Histories of Endurance and Renewal, by Patty Loew, and Many a Fine Harvest: Sauk County, 1840-1990, by Michael J. Goc. I found these books thanks to assistance from librarians at the Spring Green Community Library.

2 Living in Wisconsin has taught me that -40 Fahrenheit is equal to -40 Celsius. Now, while there are places in the U.S.A. that can get a lot colder, I still remember quizzically staring at the thin line on the bottom of the outdoor thermometer one morning, thinking it was broken.

3 In one of those magical moments, one winter day while I worked at Taliesin Preservation in the Visitor Center, all of us kept going all day to the main level to watch about 4 bald eagles stand at the edge of the ice on the river’s bend and hunt for fish.

Hey – those of you working at the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center in the winter! Keep a watch out for this, ok?