A trickster, possibly.

maybe an s.o.b.

But not a con man (not even on the order of Harold Hill).

However, I know why you think Frank Lloyd Wright was like that.

After all—

He borrowed lots of money from people and couldn’t give it back.

And pulled so much money out of former client Darwin Martin.

Check out this documentary on Wright, Martin, and Buffalo that came out in 2016. It’s great.

Then,

In 1932, Wright convinced a bunch of kids (the Taliesin Fellowship) to give him money to learn about architecture when he had no clients.

But while they paid him,

they fixed his buildings both before and after he had clients again,

Apprentices working at Hillside probably in 1933. Yeah, chiseling stone without a shirt on (like the man pictured above) isn’t up to OSHA standards, but then again, I found newspaper stories around that time in which people had to be reminded not to throw cans of used motor oil into their fireplaces to get the fire going (and usually suffered burns from the resultant explosions).

And farmed

his land,

Apprentice Bill Patrick hoes squash in a photograph on page 66 of the book: A Way of Life: An Apprenticeship with Frank Lloyd Wright, by architect Lois Davidson Gottlieb.

While working in the kitchen and serving meals.

As well as,

BUILDING

his furniture

like his drafting tables for the Hillside studio.

You know, drafting? Like, doing something people should get paid for?

Although I get the feeling that becoming an architect is like becoming a doctor: you get the degrees, then you go and work in an office.

… which you get paid for…. C’mon: stay focused!

And later,

Even when things were on the up again, they built the “camp” in the Arizona desert starting in the late 30s.

a.k.a., Taliesin West.

And that’s not counting

the whole, “leaving his wife and 6-kids” thing.

Yeah yeah yeah: it was a lot, ok?

My fingers are too tired to copy/paste all of the stories that will come up. You can read about it if you put “frank lloyd wright” and “scandal” into a search engine.

But as I told architectural historian Kathryn Smith one time:

“with Wright, there’s a difference between the ideal and the reality.”

Then,

I read The Lost Years by Anthony Alofsin. Alofsin identified Wright’s desire to create an educational community back in 1909-11. Wright thought this education would transform architecture:

Recalling the training of artists in Japan or the practice of apprenticeship in the Middle Ages, he concluded that a new education was necessary for youth, incorporating the spirit of great architecture, “the study of the nature of materials, the nature of the tools and processes at command….”

The Lost Years, 1910-1922: A Study of Influence, 90.

Not only that:

Wright seemed to honestly believe that he could build beautiful homes for less money.

Even thought the whole country didn’t take him up on that.

So, he wasn’t just full of it. I believe he actually did think it would all work out.

Moreover:

He honestly thought that, within a few years of its beginning, his apprentices wouldn’t have to pay tuition for being at the Taliesin Fellowship. He thought that the cost of their tuition would pay for itself while he created a self-sustaining community.

For example,

he wrote this in a brochure for the Taliesin Fellowship:

[T]he Fellowship has a two-hundred-acre farm, and as another there are yearly fees fixed at about what a medium-grade college education would cost plus work the apprentice can do. Eventually, paid services to Industry in architectural research will contribute substantially to put the tools needed into the hands of the workers and reduce or eventually abolish the fee so worthwhile young men and women may work for their living not as education but as culture.

The Taliesin Fellowship (brochure for the Fellowship), December 1933.

Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings, volume 3: 1931-39. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1993), 163.

And the work

in the self-sustaining community of the Fellowship would teach apprentices to be better architects. He wrote this in the 1943 edition of an Autobiography:

The field work is as important a responsibility as the work in the draughting room, or in the garden, the kitchen or the dining rooms. This seems very difficult for young America to accept. One of our young men could not see the work in the kitchen as anything but menial work to be done by a servant. When he was told he didn’t have to do it his conscience troubled him because all the others were going that work…. After the work in the kitchen he would sit and make drawings for the new arrangements he felt we needed. He would suggest new systems of serving, which would eliminate waste motions. He was just as interested in work as in any other. His knowledge of the working of a kitchen and dining room on whatever scale is instilled into his very being—a knowledge earned and gained by him by way of actual experience—not by way of a superficial inadequate theory of designing.

Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography, new and revised ed. (New York: Duell, Sloan, and Pearce, 1943), 425.

otoh:

There’s no denying what Priscilla Henken witnessed when she and her husband David were apprentices during World War II. She wrote on August 6, 1943 about the inefficiency she witnessed in the Fellowship:

“plows, rakes, hoes, wire rusting in weather of all sorts – and forgotten; berries neglected on the bushes; man power used to dress up a house instead of to repair it—all to show off for guests. Potemkin’s false front and shabby rear.”

Taliesin Diary: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Priscilla Henken (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, London, 2012), 206.

Like I said:

With Wright, there is a difference between the ideal and the reality.

December 31, 2023.

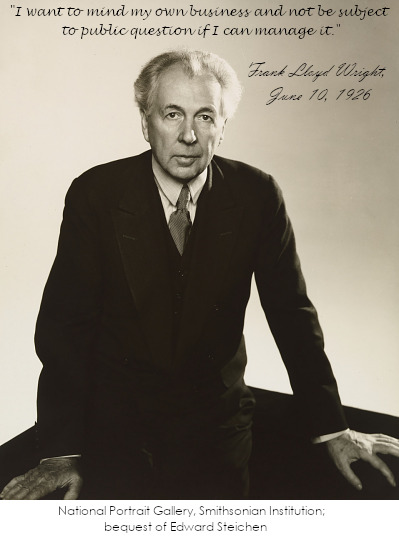

The portrait at the top of this post is available online here from the National Portrait Gallery.

I added Wright’s quote in the photo. It came from a letter he wrote the people of Spring Green that was published in the Weekly Home News on June 10, 1926 while Wright was having problems with his second wife, Miriam Noel. When I found the photograph by Edward Steichen, I thought of putting the quote in it because it’s like one of those inspirational posters that has taken a turn. I laughed so hard I cried.

Notes:

1. “Shyster” is apparently based on a German word from the 18th century. When I looked for “Shyster” on vocabulary.com, I found that:

A shyster is someone who might rip you off or do something unethical in order to get his way. A used car salesman might tell you a car is a thousand dollars, but when you read the fine print, it turns out you’ll pay a lot more. That salesman is a shyster — someone who lies and deceives for his own benefit.