Albert Rockwell took this photograph on August 15, 1914. It shows Taliesin’s burned living quarters.

WARNING: My post includes descriptions of the extreme violence that took place during Taliesin’s 1914 fire. Additionally, contemporary news reports often refer to murderer Julian Carlton as “the negro”. I’ve removed that term for Carlton when the sentences are still comprehensible, but did keep it in areas.

In this post I am dissecting what I think is the biggest myth surrounding the August 15, 1914 fire and murders at Taliesin: that the murderer sealed all of the entrances and killed everyone as they ran out of Taliesin’s one unlocked door.

Read my post on the fire for the basics and information on those killed.

And I wrote a note near the bottom of this post (1) that lists the newspapers that repeated the myth in 1914. However, I want to address the “he sealed the doors to the house” myth first.

This myth derives from something that survivor William Weston said. Here’s Weston, in the Detroit Tribune on August 16:

“As each one put his head out,” said Weston, “the Negro struck, killing or stunning his victim. I was the last…” [ellipses included]

“The ax struck me in the neck and knocked me down, but left me conscious. I got up and ran, the Negro after me. Then I fell, and he hit me again. I guess he thought he had me, because he ran back to the window and I got up and ran. When I looked back he had disappeared.“

People gravitated to this statement:

“As each one put out his head…,” Carlton “struck, killing or stunning his victim. I was the last.”

However,

the other survivor, Herbert Fritz, gave a description that day which contradicts the myth. I copied his statement on what happened. The Chicago Daily Tribune first printed this on August 16:

“I was eating in the small dining room off the kitchen with the other men,” said Fritz. “The room, I should say, was about 12 x 12 feet in size. There were two doors, one leading to the kitchen and the other opening into the court. We had just been served by Carleton and he had left the room when we noticed something flowing under the screen door from the court. We thought it was nothing but soap suds spilled outside.

“The liquid ran under my chair and I noticed the odor of gasoline. Just as I was about to remark the fact a streak of flame shot under my chair, and it looked like the whole side of the room was on fire. All of us jumped up, and I first noticed that my clothing was on fire. The window was nearer to me than the other door and so I jumped through it, intending to run down the hill to the creek and roll in it.

“It may be that the other door was locked. I don’t know. I didn’t think to try it. My first thought was to save myself. The window was only about a half a foot from the floor and three feet wide and it was the quickest way out.

Arm Broken by Fall.

“I plunged through and landed on the rocks outside. My arm was broken by the fall and the flames had eaten through my clothing and were burning me. I rolled over and over down the hill toward the creek, but stopped about half way. The fire on my clothes was out by that time and I scrambled to my feet and was about

Cont’d, p. 6? column 1

to start back up the hill when I saw Carleton come running around the house with the hatchet in his hand and strike Brodelle, who had followed me through the window.

“Then I saw Carleton run back around the house, and I followed in time to see him striking at the others as they came through the door into the court. He evidently had expected us to come out that way first and was waiting there, but ran around to the side in which the window was located when he saw me and Brodelle jump out.

“I didn’t see which way Carlton went. My arm was paining me, and I was suffering terribly from the burns, and I supposed I must have lost consciousness for a few moments. I remember staggering around the corner of the house and seeing Carleton striking at the other men as they came through the door, and when I looked again the negro was gone.”

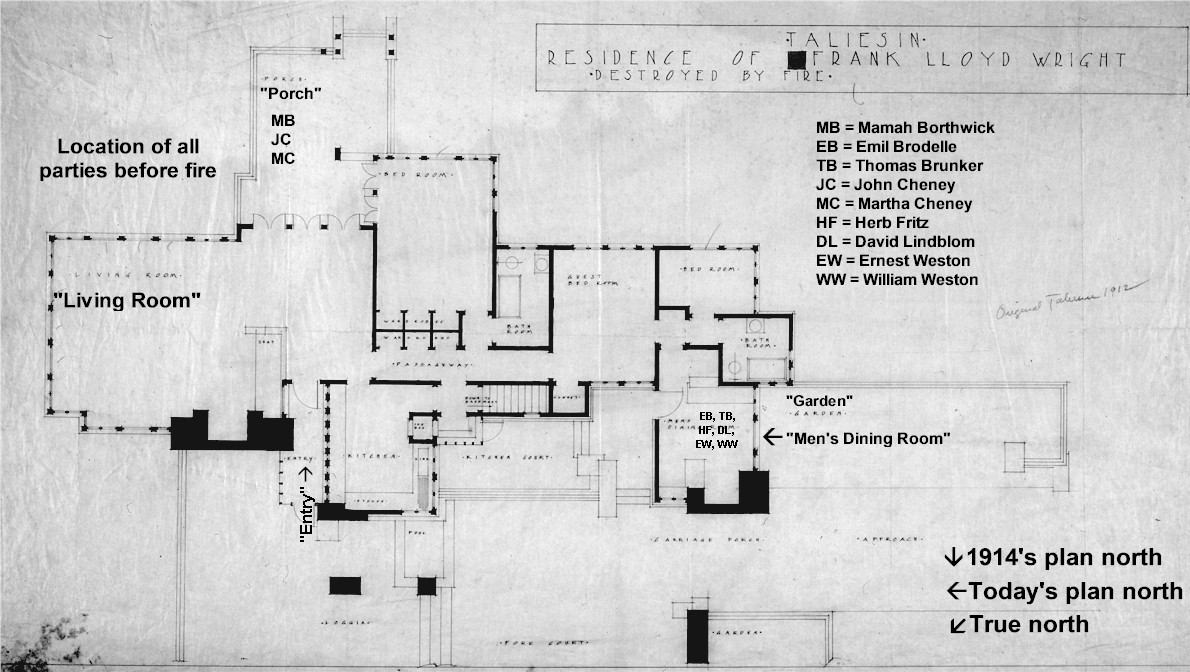

Showing where everyone sat that day:

I determined everyone’s location due to work by other Wright biographers, and the article in the August 20, 1914 edition of the Weekly Home News (the newspaper of Spring Green). The Home News had the best article on the fire and murders.

I wrote the room in which each person sat on the drawing from 1914, below. The words, “living room”, “porch” and “men’s dining room” appear on the actual drawing:

JSTOR also has this drawing on-line.

One person (Herbert Fritz) escaped through the south window without being touched. On the other hand, Julian Carlton attacked two men (Brodelle and Wm. Weston) who exited on that same side (the arrow with “Men’s Dining Room” is pointing at the room’s south wall). Carlton also attacked three that came out of the door on the north side of the room (Thomas Brunker, David Lindblom, and Ernest Weston). The details about the attacks on those three are not known.

Looking at what happened and what Fritz and Weston said, it appears that Weston witnessed:

-

-

-

- Fritz jumping out of the window,

- Emil Brodelle next jumped through the same window, where Carlton struck him, then

- Weston jumped. Carlton almost fatally struck Weston, who must have also been on fire.

-

-

Regardless,

people interpreted Weston’s quote, that “[a]s each one put out his head,” as “everyone attacked that day came through one door with Carlton waiting on the other side.”

The Chicago Daily Tribune printed Herbert Fritz’s statements that, “It may be that the other door was locked. I don’t know. I didn’t think to try it. My first thought was to save myself.” However, most other newspapers put the myth (the interpretation of Weston’s statements) into print. And newspapers often printed that Carlton locked all of the doors except for one.

Then, adding to the gruesomeness,

is the fiction that everyone at Taliesin stuck their heads out of Taliesin’s windows. In fact, the Chicago Daily Tribune states on August 16 that Carlton, “dashed at Weston and chopped at his head as the carpenter thrust it out the door.”

On that same day, the Decatur Daily Review wrote that Borthwick: “was the first to put her head through the window to escape the intense heat.” And that Carlton “struck her down with one blow, crushing her skull.”

Yet, no one saw Carlton attacking her, or her children.

The October 4, 1914 issue of the Washington Post has this:

Mamah Borthwick made a dash through the window. As she went out a hatched[sic] crashed into her head. Her innocent little son jumped after his mother. He, too, was killed by the hatchet. Then the daughter jumped. She was stricken down. One by one the guests jumped out, not knowing what had happened to the others. Each one was struck down. When the murderer was finished six lay dead and three wounded seriously.

The particularly violent and horrific narrative that the murderer stood outside of the one unlocked door is consistent in the contemporary news stories. And this, while even Nancy Horan wrote in Loving Frank that three of the victims—Mamah Borthwick and her children, John and Martha Cheney—sat in the terrace off Taliesin’s living room.

You can see where people sat in the drawing I put above.

This narrative stays because it’s so grisly.

In addition, in 1914, it was conveniently racist: of course, a fiendish Black man killed all those people. But, even more so, he did it with superhuman (animal?) speed and cruelty.

This detail, then, has been written in biographies and historical books. I didn’t start to get closer to this until I thought I really needed to read the primary sources.

That was when I realized people writing in 1914 were wrong about things at the time. Of course they were! On August 15 and 16, 1914, they were there, taking notes while trying to make sense of a pile of burning rubble that had once been a house. One that most had never seen before.

First published August 12, 2022.

A.S. Rockwell took the photograph at the top of this post on the day of, or the day after, the fire. The photograph in on Wikimedia Commons and is in the public domain. See here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Taliesin_After_Fire.jpg for information about the origin of the photograph.

Notes:

1 Newspapers where the myth was first printed:

The Chicago Daily Tribune, Aug. 16; the Decatur Daily Review, Aug. 16; the Detroit Tribune, Aug. 16; the Daily Clintonian, Aug. 17; the Des Moines Daily Review, Aug. 18; the Richland Democrat, Aug. 19; the Waterloo Evening Courier, Aug. 19; the Winchester Journal, Aug. 19 and the Camden Record on Aug.. 20 (both of which reprinted the Clintonian news report); and, repeated from the Judson News story is the Wanatah Mirror and the Westville Indicator of Aug. 20, the Monon News and most of the story in the Roann Clarion on Aug. 21; Spring Green’s newspaper, the Weekly Home News on Aug. 20 (which otherwise is probably the best reporting of the 1914 fire and murders); and the Washington Post on October 4.