Jennie and Nell Lloyd Jones that is.

I have to approach them that way—

As the Big Boy’s Aunts

—or I wouldn’t get as much interest on this post.

They were the first of the Lloyd Joneses born in Wisconsin. Their three brothers and three surviving sisters (including Wright’s mother) had been born in Wales, starting in 1830. Aunt Nell was born in 1845, and Aunt Jennie in 1848.

My post today will be about them. That’s because

on March 9, 1887

Aunt Nell wrote to her nephew

newly arrived in Chicago

about working on a building plan.

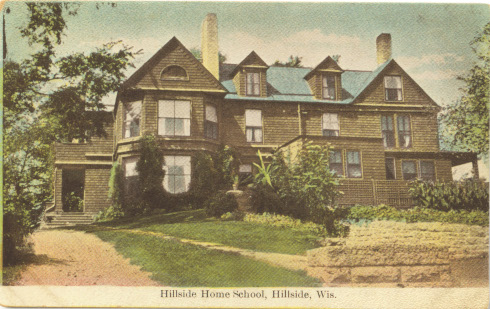

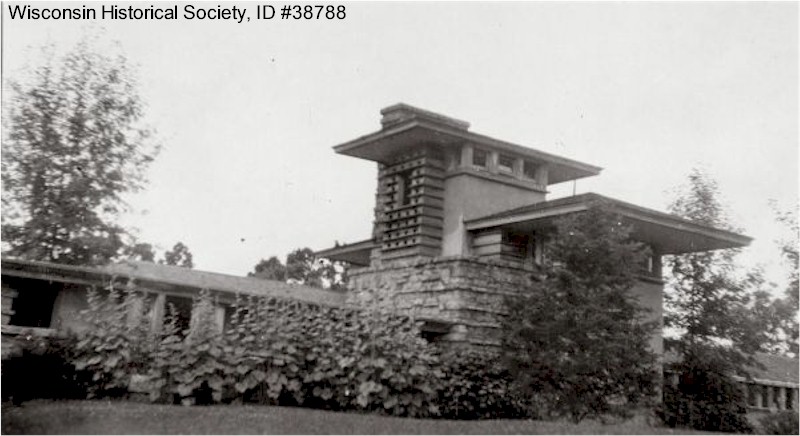

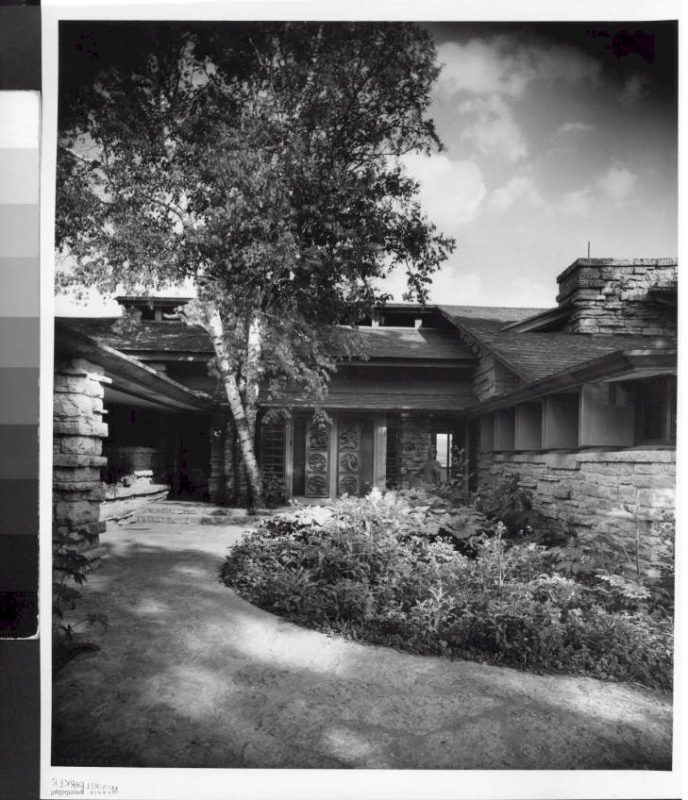

That building–in the postcard at the top of this post–would be the newest construction on their planned school; as well as the first structure that Wright ever designed.

Hold on a moment.

before I get to Nell’s letter, I want to write more about the Aunts.

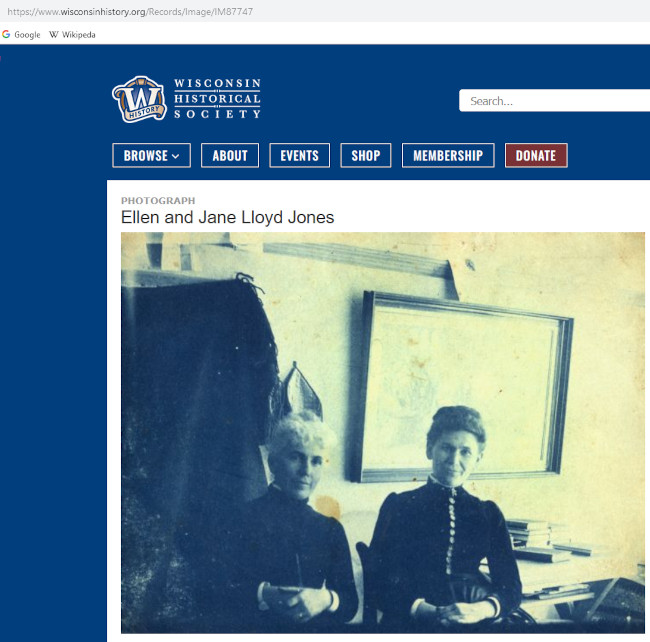

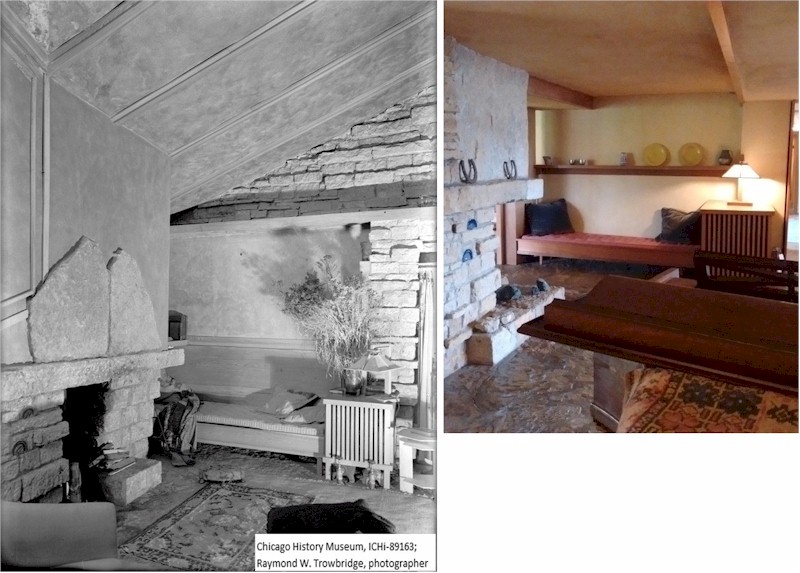

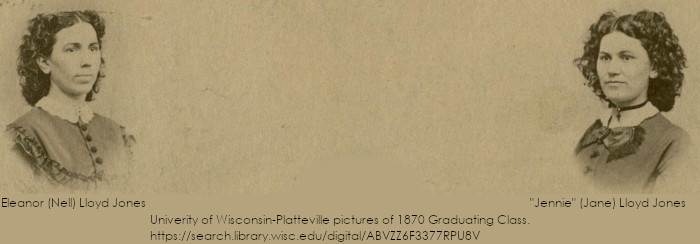

They never married and graduated from the University of Wisconsin-Platteville Normal School in 1870. Here’s a photo from the class of 1870, below.

25-year-old Nell is on the left, and 22-year-old Jennie is on the right.

This is my screengrab of the photograph by John Robertson, at the University of Wisconsin—Platteville. Archives and Area Research Center. Local Identifier: Record #889.

You can see the page with the whole photo of the class here.

The Wisconsin Historical Society has a photo of them at their school after 1887:

Aunt Nell is on the left with the white hair.

Nell’s white hair:

Wright’s sister, Maginel, wrote about this in The Valley of the God-Almighty Joneses:

Aunt Nell’s face had been badly scarred by smallpox… and her hair had turned snow white during the illness. Once, years later, she told me about it. At the time she fell ill she had been engaged to a young man with whom she was deeply in love…. then,… she was stricken, and lay for weeks horribly ill…..

When her fiancé came to see her he was appalled. He stayed for awhile, and… promised to return the next day. He never came back….

“Oh,” I said to her, “Aunt Nell, how did you bear it? What did you do?”

She gave me a grim little smile. “I hoed onions, my dear,” she said. “I just hoed onions all summer long.”…

Maginel Wright Barney, The Valley of the God-Almighty Joneses: Reminiscences of Frank Lloyd Wright’s Sister (Unity Chapel Publications, Spring Green, Wisconsin, 1965), 118-120.

Onions?

Did Nell have onions on her belt because that was the style at the time?

No.

During the American Civil War, people were asked to raise onions which could be sent to the soldiers to protect against scurvy.1

Did Maginel also write about Jennie’s personal life?2

Here’s part of what Maginel wrote:

Aunt Jennie… was merry and animated…. It was she who told me stories of the family’s beginnings in Wales, and of their venturing to the primeval forests in Wisconsin…. Aunt Jennie had a romantic heart; yet she never married….

“The Valley of the….”, 119-120.

Some of Maginel’s memories are wrong. She wrote that Jenkin was 16 when he joined the Army. Jenk, the last of the Lloyd Jones children born in Wales, was born in 1843. The Civil War started in 1861, when he was 18. So, they must have been raising onions for the troops at that time, too. Maginel wrote that Nell’s hair went white the summer she had recovered from Small pox and had her heart broken.

Yet

the photo in 1870 of the graduating class from UW-Platteville shows Nell with jet-black hair.

So, either Nell conflated the story of the heartbreak and hoeing onions, or her niece Maginel did. Or maybe Nell had her heart broken twice.

As for Jennie –

Why didn’t she marry? Jennie told Maginel that she just couldn’t say yes to any of the men who asked her to marry them.

Maybe that contributed to the story Taliesin tour guides had created when I was there: that the two sisters vowed never to marry because one was romantically wounded.

Read my correction on this in the next post, “More on Frank Lloyd Wright’s aunts“.

Well, their decision to devote their lives to education is good for all of us.

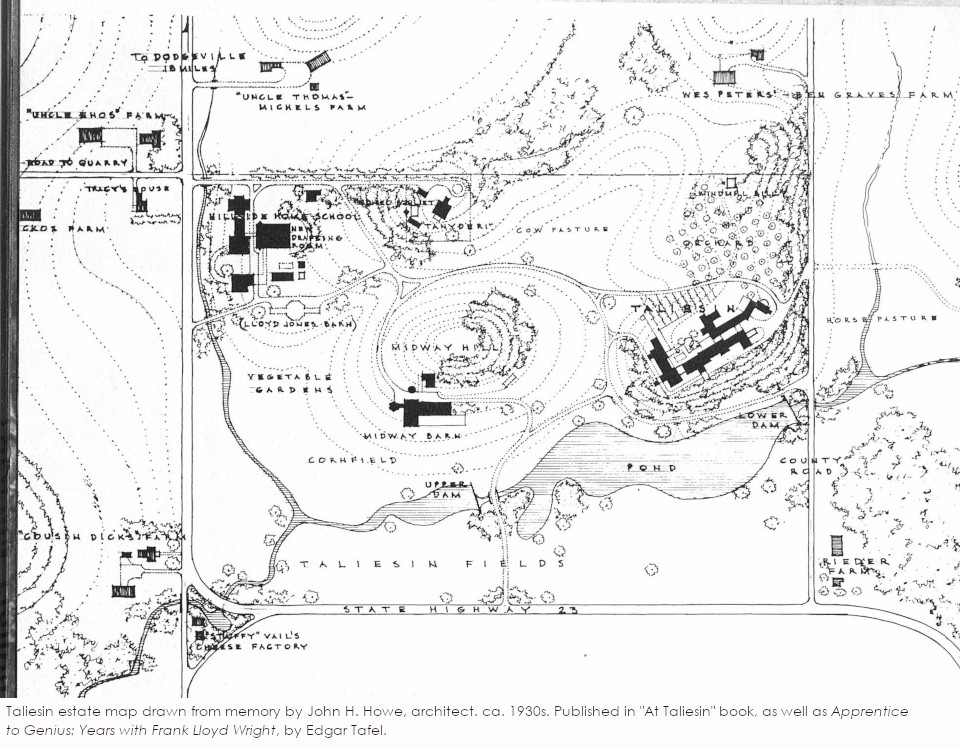

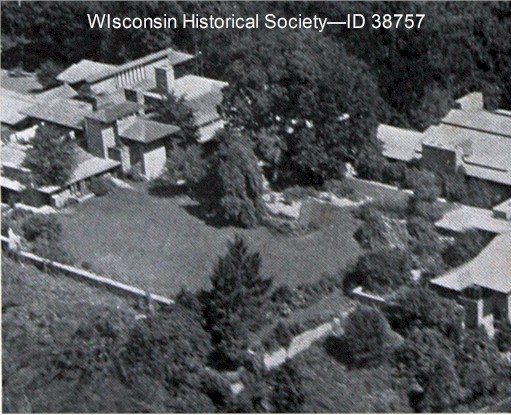

Because they created and ran the Hillside Home School for 28 years.

1887 to 1915

NOW

I get to why I’m writing today. In early 1887, Jennie and Nell decided to start their school in The Valley.

Nell taught history at the Normal school in River Falls, Wisconsin, and Jennie was then an instructor in a kindergarten teacher training school in St. Paul, Minnesota.

Then Nell wrote to “My Dear Frank“,

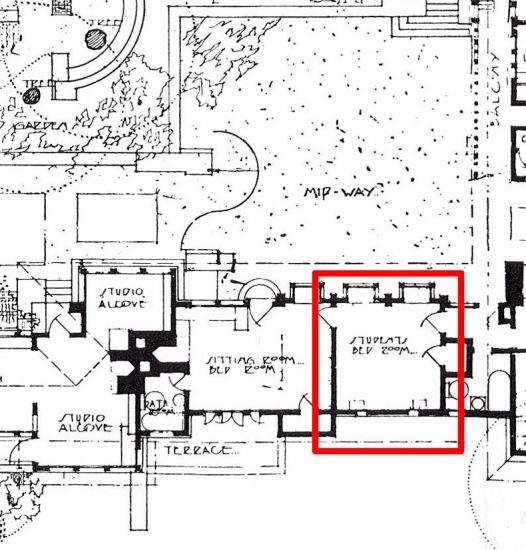

Nell wrote “I heard you have been down to Hillside to look the ground over”.

SO, obviously the Aunts had spoken to him before about designing a building.

And while an unknown woman, “Miss Daniels”, had been drawing the beginning of the plan, “Miss D.—” didn’t feel it was finished/good enough.

Then Nell wrote details about the plan on what they wanted.

The new building

- Should face east

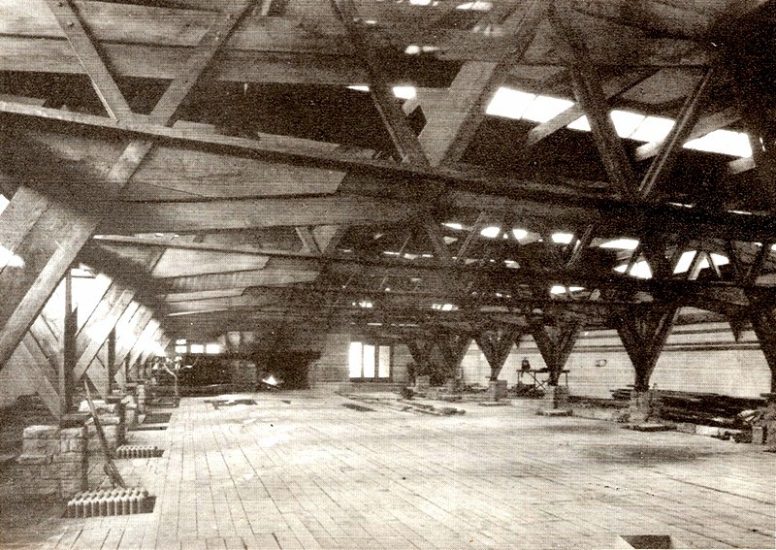

- The first floor would have a room of 26 X 28 feet [67.6 square meters] to be used as a parlor or perhaps dining, and have an open staircase

- One upstairs bathroom

- Several small rooms – 6?

- And two larger rooms over the kitchen

- I’m guessing those rooms were the Aunts’ bedrooms

She wrote a few more things, like that they didn’t need closets. And they hoped to start “in the spring”.

Then Nell finished her letter with,

I hope you are well, happy and satisfying Mr. Silsbee.3

I write in great haste but with much love

Ellen C. Lloyd Jones to Frank Lloyd Wright, March 9, 1887. Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives, FICHEID: J001A03.

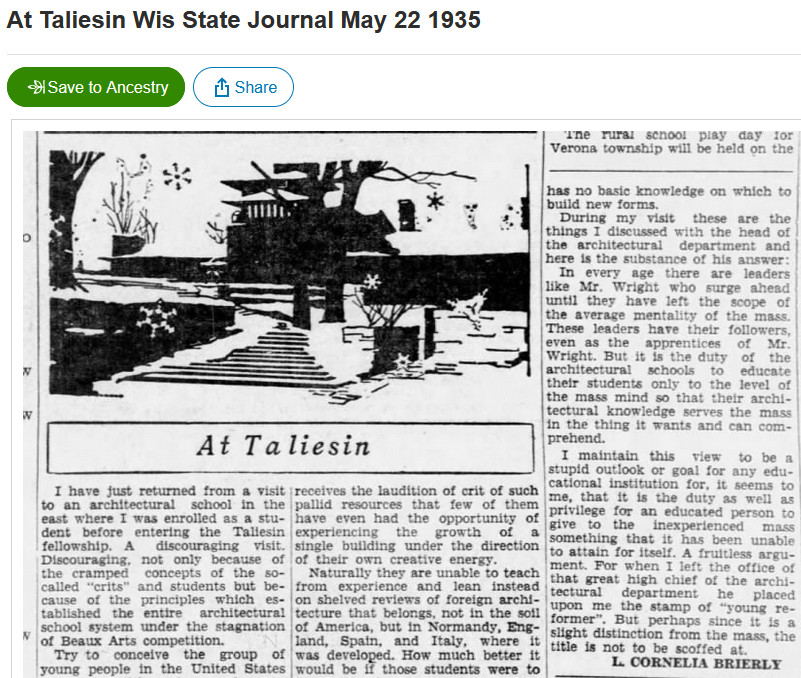

Construction on the building didn’t start in the spring, but they finished it in November.

We know that because of the “Home News”

It tells us that the Hillside Home School opened the week of September 22. And, then there’s this in the Weekly Home News from

the week of November 10

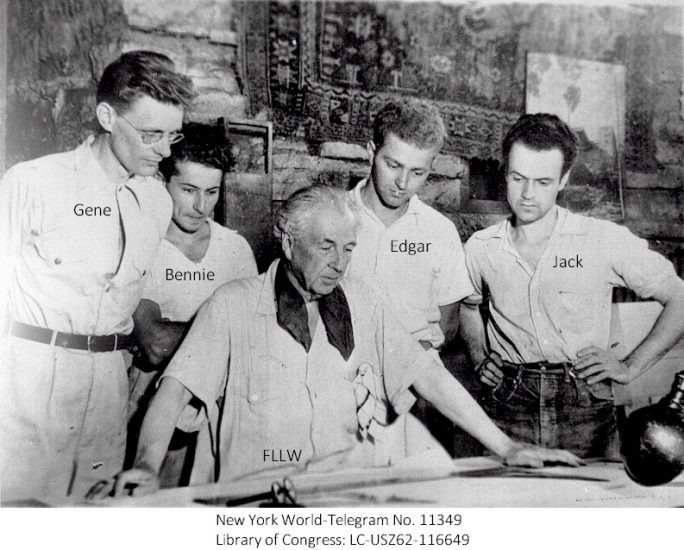

Frank Lloyd Wright of J.L. Silsbee architectural firm of Chicago here to finish up details and supervise the clearing and grading of grounds. “Mr. Wright is an able young artist and if all had a ‘barrel of money’ with which to carry out his attractive mansion and cottage plans they might be happy yet.”

It’s likely this positive description came from The Aunts. Because Wright himself was just 20 years old.

More links:

Georgia Snoke (a member of the Lloyd Jones family, from the Jenkin Line), crafted a nice write-up on the Aunts from unitychapel.org (the website kept by the Lloyd Jones family). That page is available at this link: http://www.unitychapel.org/the-aunts.

Georgia provides information on the Aunts’ emotional lives, which may help to illuminate why these two women never married.

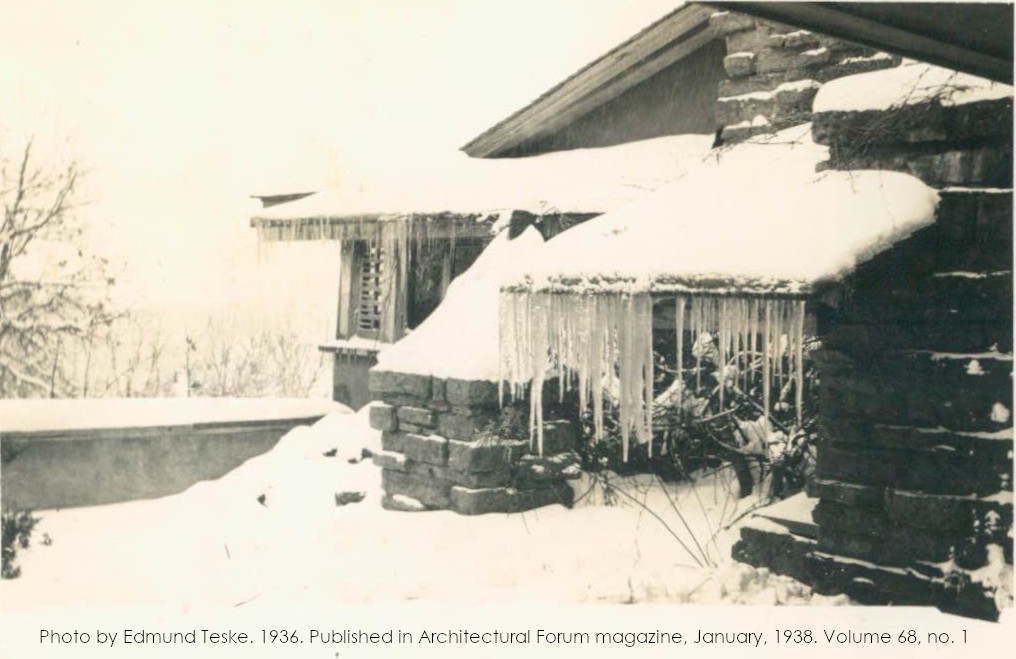

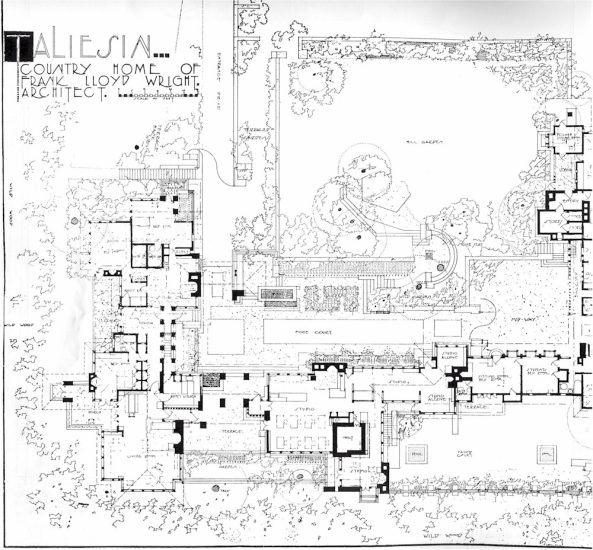

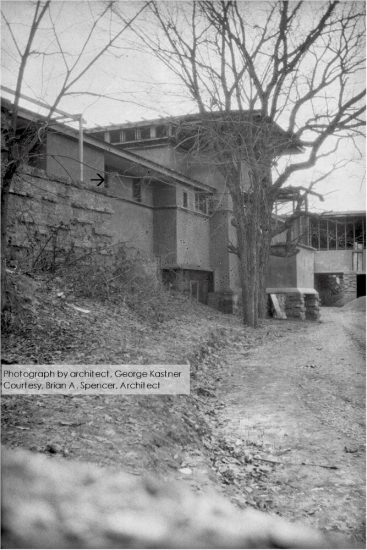

The postcard at the top of this post looks up and west at the Home Building that Wright designed for the Hillside Home School in 1887.

It’s available in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Taliesin, Illustrated by Vintage Post Cards, by Randolph C. Henning, 87.

First published February 7, 2024.

Notes

1. “Onions were used to protect against scurvy” is another thing I learned while working at Taliesin.

2. Why do you keep calling her Jennie when The Master called her Jane?

She was known as Jennie all over the place. She was identified as that in the UW-Platteville photo, on photos of her while the Hillside Home School ran, and by Maginel in “Valley of the God-Almighty…”. As I wrote in my first Hillside Home School post, Wright’s sister was named Jane, but known as Jennie. So I think that’s why Wright referred to his aunt as Jane. I’m insistent on this because it seems that she wanted to be known as Jennie.

3. Wright’s first employer, Joseph Lyman Silsbee (1848-1913).