Drawing of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York City.

My post this week is going to be about where Wright designed the Guggenheim Museum

He designed it in New York City, you silly!

No. I mean:

in which of his studios did Wright first draw the plan for the museum?

See, the Guggenheim is one of Wright’s most famous buildings, but the story of its commission and design isn’t the cinematic

possibly apocryphal

story of Wright drawing of Fallingwater in two-and-a-half hours while the client drove from Milwaukee.

And the tale took a bit longer.

And while Wright received the commission in 1943—looong story short—it was still being built when he died in 1959.

The biz on the Gugg:

While there’s no question he designed it in a Wisconsin studio

He couldn’t go to Taliesin West in the early 1940s because of gasoline and rubber rationing,

I’ve never come across any apprentice remembering Wright first envisioning its plan, or talking about his ideas for it.

Therefore: I’ve been trying to find the exact studio where Wright first put pencil to paper. Like:

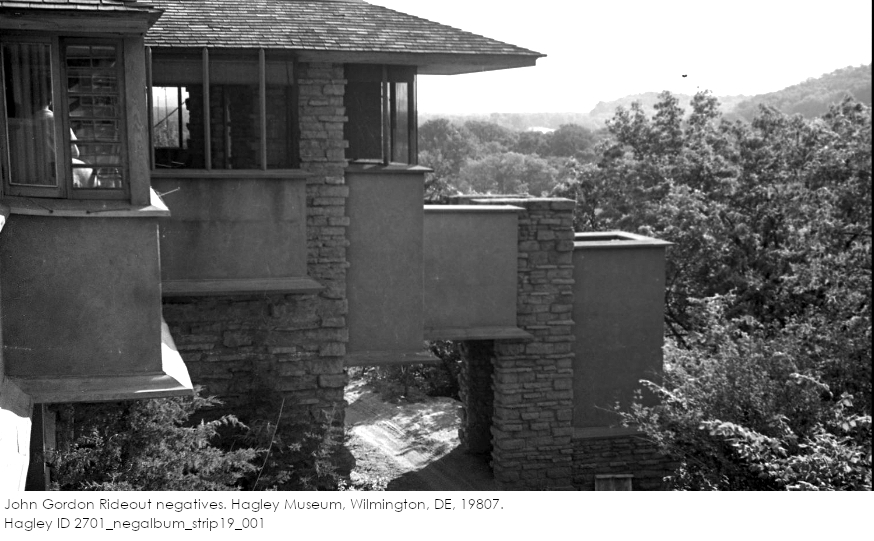

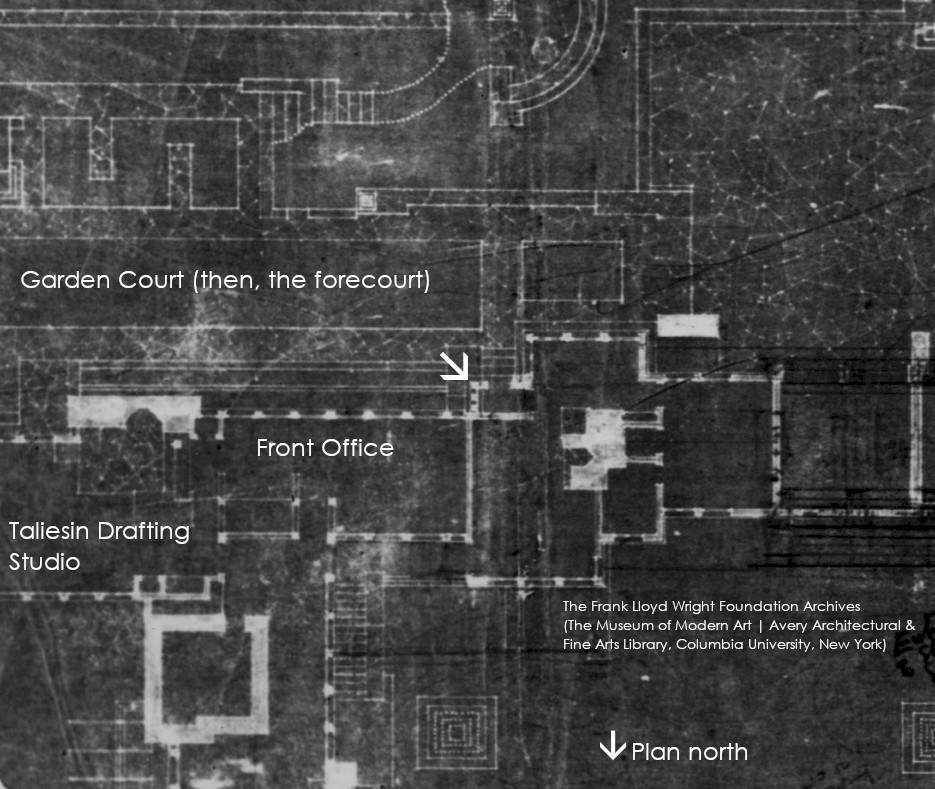

Did he do it in the Taliesin studio?

Or in the studio at Hillside?

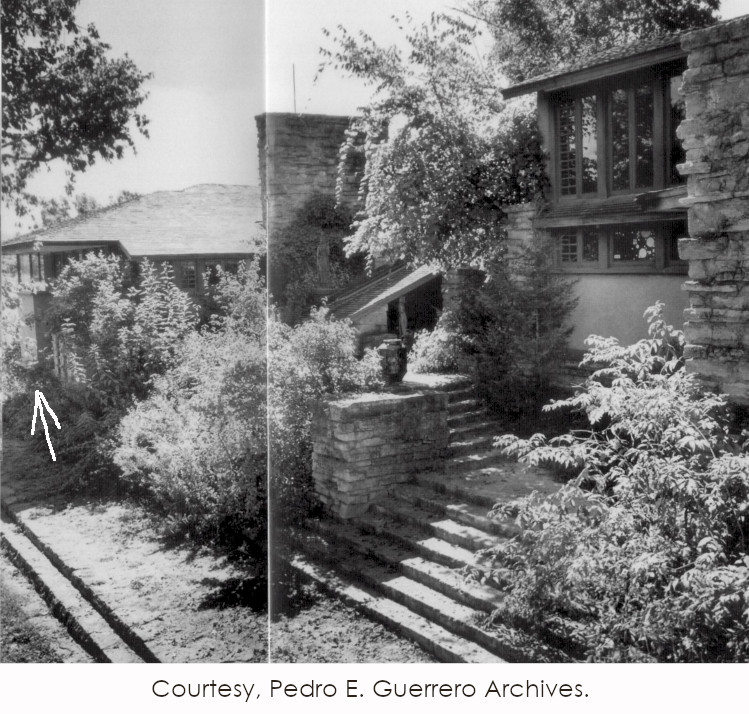

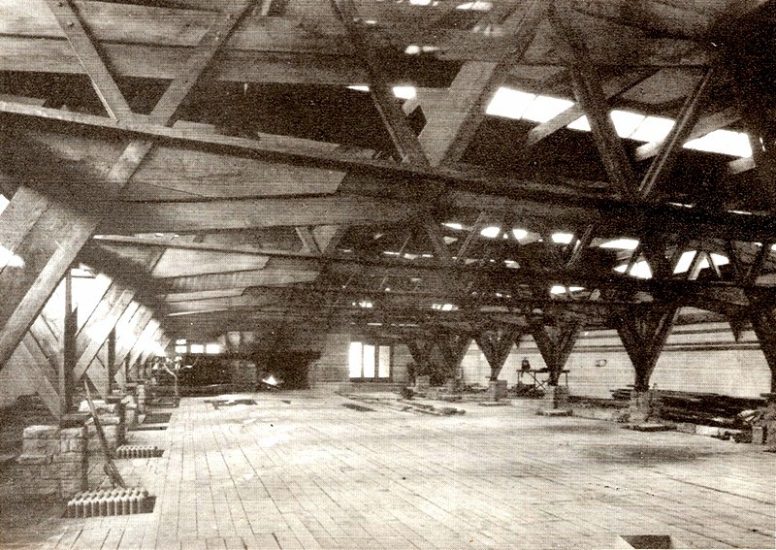

This is a photo that I took in the Hillside drafting studio in April 2006. While there are items on the tables, I think that for the most part no one in the Taliesin Fellowship or at the School of Architecture was at that time currently in residence. Even in 2006 they usually didn’t “land” in Wisconsin until May.

Yet, when I first started in tours, I probably thought he drew it at Hillside.

After all, Hillside had his main studio there for decades as of the late 1930s.1

Yet

In 1995, former apprentice Curtis Besinger published Working With Mr. Wright: What It Was Like. That came out in ’95

Besinger wrote

that,

by the end of December 1942 there were only eleven of us remaining at Taliesin.

Curtis Besinger, Working With Mr. Wright, 139-140.

Besinger wrote that there were less people in The Taliesin Fellowship due to World War 2.2 So then I thought maybe Wright only used the studio at the Taliesin structure.

But then

I read Taliesin Diary by Priscilla Henken. That came out in 2012.

She and her husband were at Taliesin in 1942-43.

In her diary on July 9, 1943, she wrote that Wright went to New York City because:

“It’s quite definite that FL [sic] has signed the contract for the Guggenheim museum and Robert Moses is showing him the sites.”

Taliesin Diary: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Priscilla Henken (W.W. Norton & Co., New York, London, 2012), 191.

So I thought again. She wrote this entry in July. So maybe they had moved to the Hillside studio for the summer?

Well, I told myself: do what you always do:

CHECK THE DAMNED PHOTOS.

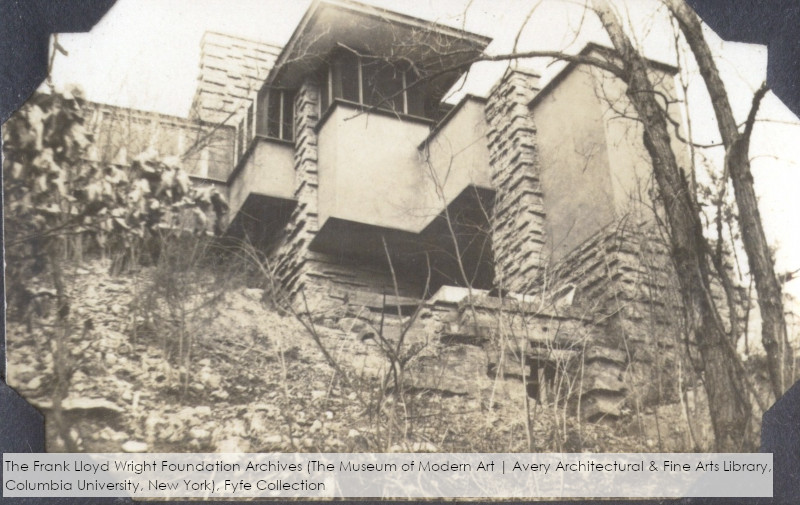

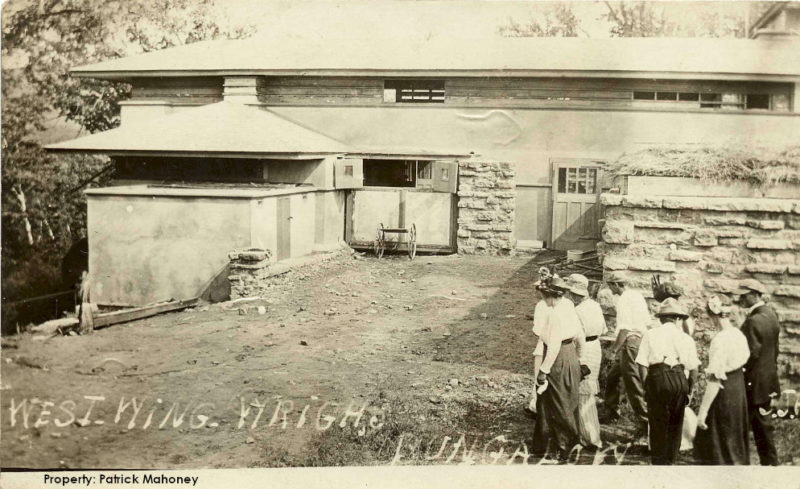

Here’s one in Taliesin Diary taken in 1942-43:

While Fellowship members practiced choir in the space, you can see 2 drafting tables that Wright or others could use .

Further, I read from the book The Architecture of Frank Lloyd Wright3 by Neil Levine. On page 320 in Chapter 10: “The Guggenheim’s Logic of Inversion”, Levine wrote that, during the summer of 1943, “no drawings exist” of the Guggenheim “from this preliminary stage”.

which, okay, means I didn’t have to look at photos; but it’s still neat to see. You should get the book. Hey, don’t cry to me if you don’t see the book for yourself.

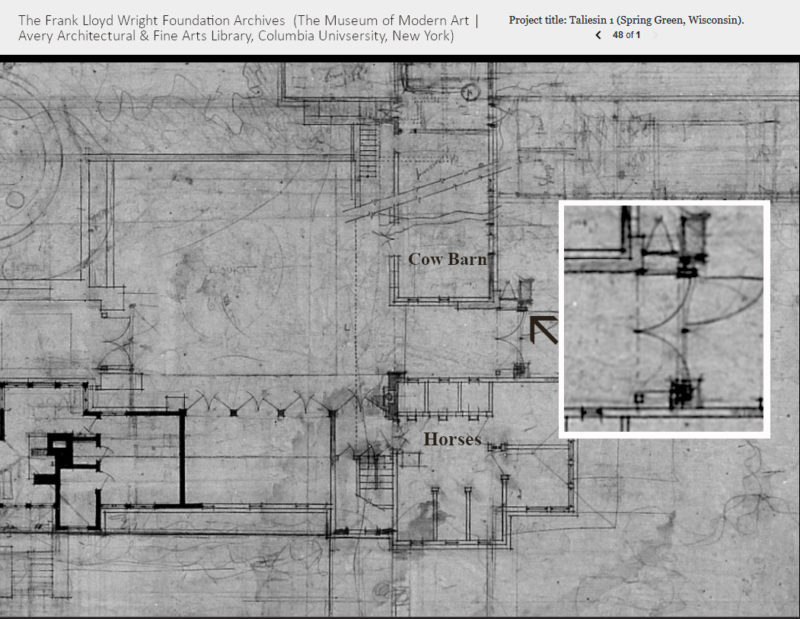

And while the Guggenheim’s building site hadn’t yet been chosen by fall 1943, archives director Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer identified an early sketch from September 1943. That’s drawing 4305.002, below:

Neil Levine also posted Wright’s telegram

to the person who encouraged Solomon Guggenheim to contact Wright. That was Guggenheim’s Curator, Hilla Rebay:

BELIEVE THAT BY CHANGING OUT IDEA OF A BUILDING FROM HORIZONTAL TO PERPENDICULAR WE CAN GO WHERE WE PLEASE. WOULD LIKE TO PRESENT THE IMPLICATIONS OF THIS CHANGE TO MR. GUGGENHEIM FOR SANCTION.

Written by Wright to Rebay, December 30, 1943, Microfiche ID# G054C06.

According to Levine,

Rebay encouraged Wright to expand his building plans. This way, perhaps “they would entice Guggenheim into building….”

The Architecture Of Frank Lloyd Wright, 321.

In January 1944, Wright sent a communication to Rebay that:

[T]he antique Ziggurat has great possibilities for our building. We will see. We can use it either top side down or down side top.’ …”

and

“we’ll have some fun with the modern version of a Ziggurat.”4

Then, in the book,

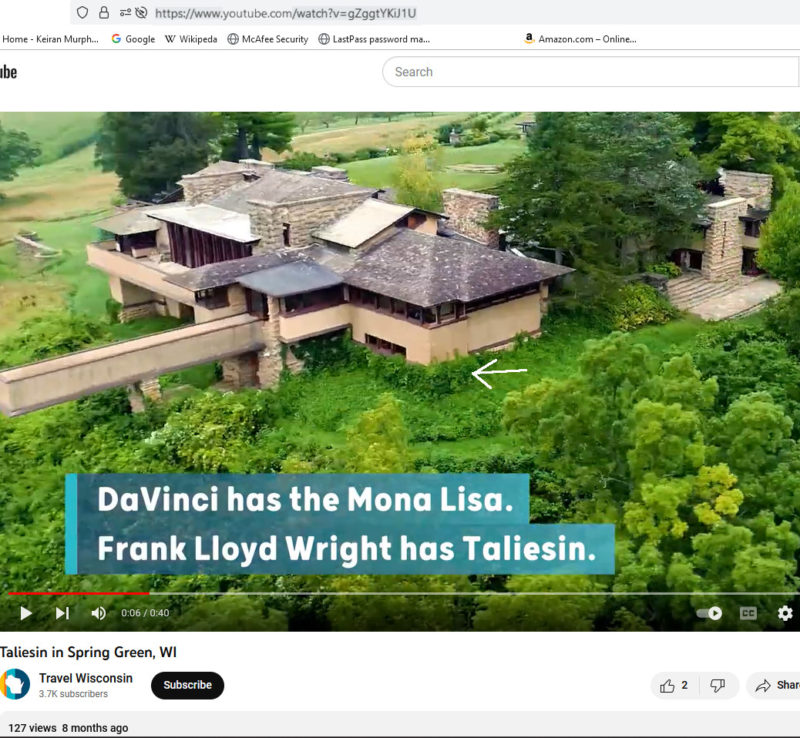

Building With Wright: An Illustrated Memoir, Wright’s clients, Herbert and Katherine Jacobs, gave us an idea of how Wright was developing things in early 1944. Herbert Jacobs (who wrote “Building With…”) relayed how the two had driven to Taliesin in February 1944 to see the plans for their second Wright house.

Herbert Jacobs wrote in the book that as the couple waited for Wright in the Taliesin studio that day (February 13), they saw “no less than eight colored sketches which we learned later were of the proposed Guggenheim museum.”5

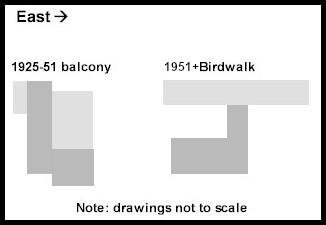

It seems that, in this early design process, Wright was playing around with how to design the Guggenheim. As a building that got larger near the earth (like ancient Ziggurats), or a ziggurat that is larger up top than at the bottom.

Wright proposed this idea to Hilla Rebay as he developed the design for the Guggenheim, writing again that:

“We can use it either top side down or down side top.“

He meant that he could use the figure of a ziggurat, like in the drawing they made below:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architecture and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

btw: this is not Photoshop joke on my part. This is an actual image of a real drawing of the Guggenheim. Although I don’t think the intense pink color was seriously contemplated. Although in a way, pulling out the idea that Wright might have through about a pink Gugg is like a card you can pull out of your deck. Similar to “Frank Lloyd Wright’s son designed Lincoln Logs.”

Or design the Guggenheim Museum like you see in the drawing at the top of this page: larger at the top.

Obviously the later idea worked and I used to tell people on my tours that neither men walked into the completed building.

First published July 4, 2024.

The number of the drawing at the top of this post is 4305.629. You can find it online here.

Notes:

1. I know that thanks to former apprentice Kenn Lockhart and Indira Berndtson (retired administrator of historic studies, collections and exhibitions for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation). “Indira” interviewed “Kenn” on July 27, 1990. They started the interview in the Taliesin studio and Kenn explained that when he applied in 1939 (c. July 5) to be an apprentice that all of the drafting was done at Taliesin’s drafting studio. Then he said, when he started his apprenticeship

“[O]n July 8, one week later, the [Hillside] drafting room floor was finished and everything was set up for drawing.“

Regarding the move to the Hillside studio:

“So July 8th, 1939 was the big move from here [the Taliesin studio]. And then he used this for client interviews and so forth….”

p. 15 of the transcribed interview.

2. Some were drafted into the service; some others signed up (like Pedro Guerrero). But still others were in CO camps or jail. “CO” camps were for conscientious objectors. In fact, Besinger wasn’t there for 3 years after being put in jail in 1943. The Federal Bureau of Investigation apparently investigated Wright, trying to discern whether or not he was influencing these young men to be against the war effort. Wright biographer Meryle Secrest showed that the FBI concluded that Wright saw the two world wars as an example of British imperialism; and therefore, he wasn’t un-American: just anti-British. [Meryle Secrest. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, New York City, 1992), 264.]

3. Princeton University Press, Princeton, 1996.

4. Prof. Levine quoted from the book Frank Lloyd Wright: The Guggenheim Correspondence, ed. Bruce Brooks (Press at California State University, and Southern Illinois University Press; in Fresno, California and Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois; 1986) for the letters from Wright to Rebay. The letter that Levine quoted from was written January 26, 1944 and appeared in Guggenheim Correspondence, 42.

5. Building With Wright: An Illustrated Memoir, by Herbert Jacobs, with Katherine Jacobs (Chronicle Books: A Prism Edition, San Francisco, 1978), 83.