Looking south in the Hillside Drafting Studio, with its flooring.

The black and white photograph on the right shows the V.C. Morris Gift Shop, designed by Frank Lloyd Wright in San Francisco (currently a men’s clothing store).

In this post, I am diving into the flooring at the Hillside Drafting Studio on Wright’s Taliesin Estate. I wrote about Hillside here. Hillside’s Drafting Studio, added in the 1930s, is 5,000 sq feet of space (1,524 m2). The Hillside Studio became Wright’s main studio in Wisconsin after the Taliesin Fellowship completed it.

There was one real point of curiosity about the studio’s flooring, which has pinstripes. This post concentrates on that flooring.

As I wrote before in my Hillside post, the Taliesin Fellowship apprentices, in the 1930s, wrote about working on the studio. Here, in the September 5, 1937 “At Taliesin”1 article, an apprentice writes that:

“…. Two months of continual and concentrated group activity by the Fellowship should announce the fact that our principal workroom – an abstract forest in oak timber and sandstone – is in order. Then watch our dust!”2

Uh… not yet

The Fellowship, and Wright, only started using the studio full-time in 1939.

Wait – what? Why not?

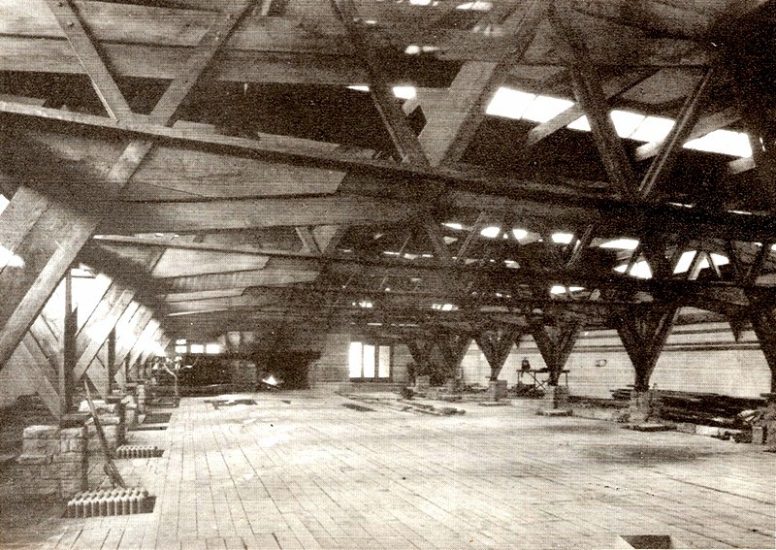

Well, the structure had been built, but it didn’t have a finished floor. You can see a photograph of the unfinished floor in a photo below. It was taken in 1937 by Ken Hedrich for the magazine, Architectural Forum. Its January 1938 edition concentrated on Wright.

Ken photographed the Taliesin estate, while his brother, Bill Hedrich, went to Pennsylvania and took the first, famous, photograph of Fallingwater (the house over the waterfall).3

While Bill photographed elsewhere, Ken photographed all over the Taliesin estate. His work included the Hillside Studio and you can see the state of it in the fall of 1937:

1938 Architectural Forum magazine issue: January 1938, volume 68, number 1, 18.

This photograph looks north in the Hillside Drafting Studio. Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship did not yet use the studio, because the room did not have its finished flooring.

When you walk into the studio today you see a wooden, waxed flooring, that has pinstripes. These pinstripes were not painted on the floor surface. What one sees is the veneered wood on its side. It’s as if you are seeing the edge of a wafer cookie.

To illustrate the “wafer cookie” look

I’ll show a photograph of the edge of some of the flooring:

I took this photograph.

Wright only used this type of flooring in one other place: on the mezzanine in “Wingspread“. That’s the name of a house he designed in Wisconsin for Herbert Johnson. Here are some of my pictures from that:

I took this photograph by the grand fireplace at Wingspread. Most of the people in this photograph worked in the Taliesin tour program.

The photograph below is the flooring of the mezzanine that matches what’s at the Hillside studio.

I took this closeup of the mezzanine flooring.

I don’t know Wright’s thoughts on the flooring.

However:

I know where it came from, when it was installed in the Hillside studio, and when Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship started studio operations in there.

That’s all because of someone else’s work.

We know the month they moved to the Hillside Drafting Studio because of Kenneth B. Lockhart (1914-1994). He arrived in the Taliesin Fellowship in 1939. The Administrator of Historic Studies of the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation interviewed Lockhart several times. In their May 5, 1988 interview, “Kenn” [sic] said that he arrived as an apprentice right after Wright and the Fellowship moved to the Hillside studio in July, 1939.

Where the flooring comes from:

That flooring caused curiosity for years. Where did it come from? And Herbert Johnson’s name floated around in the tour program in relation to that flooring. Did Johnson give the flooring to Wright? Was the flooring first planned for Wingspread? Was the flooring “overdraft” from Wingspread?

The answer to questions one and three, by the way, is NO

Yet, the question on how Wright got the flooring still had to be answered. And it was, by the Administrator of Historic Studies. In 1992, Indira tracked down its history. She started her task by asking former architectural Wright apprentice, Edgar Tafel.

Tafel had worked on the Johnson Wax World Headquarters, also commissioned by Herbert Johnson.

This is the same Edgar Tafel who wrote Apprentice to Genius.

Tafel told Indira that he thought of a connection between the Evans Products Co. and Frank Lloyd Wright. With that in mind, she went looking in Wright’s correspondence.

Correspondence between Wright and Evans Products Co.

There are 8 letters between that business and Wright (or his secretary, Gene Masselink).

The first letter (E030C06) was written on March 15, 1940. Their records indicate that they shipped flooring to Wright on November 28, 1938, but hadn’t yet been paid (the bill was $400.00).

Wright replied (E03D01) on March 22, 1940. He wrote that he appreciated their patience regarding the “laminated flooring in our draughting [sic] room.”

And he wrote that it had been difficult getting paid by clients. Yet, the flooring has been doing “good work for you – as well as for us” as at least a hundred people go through the buildings during the summer and have admired the “beauty and durability of the floor.”

Unfortunately, there does not appear to be a record that Wright ever paid the Evans Products Co.

One of the last letters from the Evans Product Co. was written on September 26, 1941. This is #E033E05. The author (apparently a secretary), began by noting how so many things had changed since that day they shipped the flooring to Wright on November 28, 1938.

They emphasized how Europe (then at war) had changed very much since that day. Then, they ended the letter noting that “there will always be an England” but (I’m paraphrasing here) they hoped that there would not always be a $400 outstanding debt from Frank Lloyd Wright to the Evans Products Co.!

Once more

I found this information in 2009 while working at Wright’s archives (then at Taliesin West in Arizona). I had spent months working on the history of Hillside with architectural historian, Anne Biebel (the principal of Cornerstone Preservation). And I finally answered where that flooring came from; which Indira had discovered it 17 years before!

Published October 8, 2021

I took the photograph at the top of this page on August 26, 2009.

1 “At Taliesin” was the name of weekly articles published by Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship in the 1930s. They were found, transcribed and edited by Randolph C. Henning. He published them in a book in the early 1990s. I recommended the book here and wrote about it in my post, “Books by Apprentices“

2 Randolph C. Henning, ed. and with commentary. At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937 (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois, 1991), 273.

3 Not that you’ve never heard of Fallingwater, but it’s a big world out there on the World Wide Web. So, what the hell!