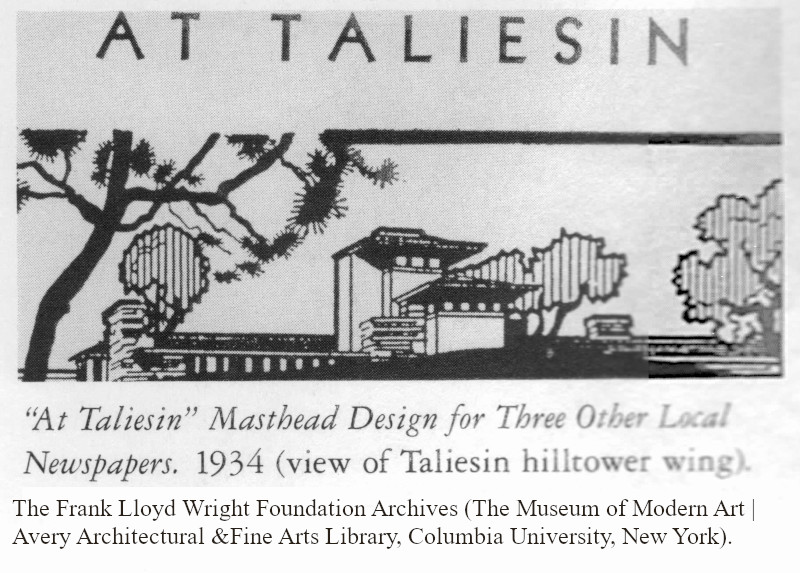

The graphic at the top of this page is one of the designs created by the Taliesin Fellowship for their weekly “At Taliesin” newspaper articles that ran from 1934 through late 1937. Architect Randolph C. Henning found these “At Taliesin” articles and put them into a book that I want to write about today.

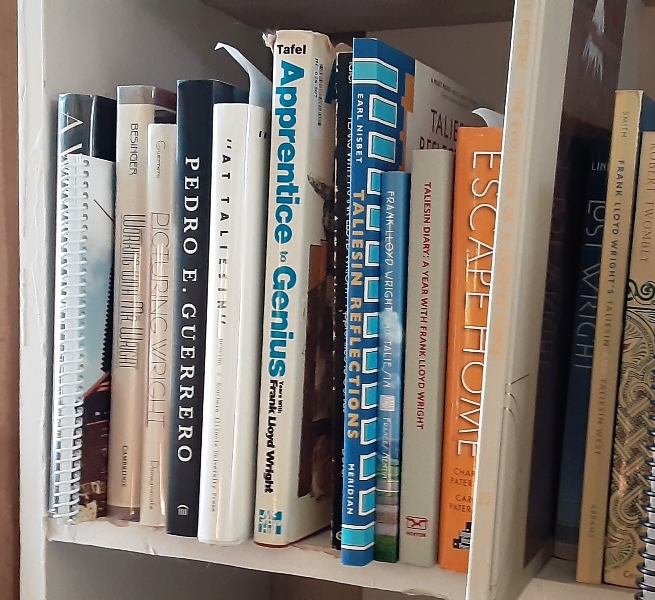

The book is

At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937, edited and with commentary by Henning (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois, 1991). I included it in the list of books I wrote about awhile ago, but I’ll concentrate on it in this post.

In part because, this book contains essential primary material about:

- Frank Lloyd Wright

- Taliesin, and

- The Taliesin Fellowship.

Before this book, the “At Taliesin” articles were relatively unknown. Henning wrote in the preface that when he decided to search for them, he thought he would find several dozen.

Or 100 “at most”.

In the end, he tracked down 285 of them. He transcribed them, edited them, and also wrote commentary on and around them. 112 articles are in the book.

The book was only published once,

in hardcover. However, many copies are still available online and elsewhere for purchase. Online aggregate www.abebooks.com is somewhere I often look for books. I typed in the title found this listing with over 30 copies.

And you could borrow it from your library.

I’m recommending it now because

once you get past its cover which looks like a college textbook

It’s actually a fun summer read.

Most of the articles fit on one to two pages. And many are just a trip. I mean that in a good way: many are a total blast.

As I wrote before:

“At Taliesin” “demonstrates why these kids in their early 20s would move out to rural Wisconsin to live and work with a man old enough to be their grandfather, and like it.“

Their insanity reminded me that, yes, there was a time in my life in which I spent 4 to 5 hours on a Friday or Saturday night on a roof playing drums.

I was not a drummer. I was 21 years old.

Oh, that time passed quickly.

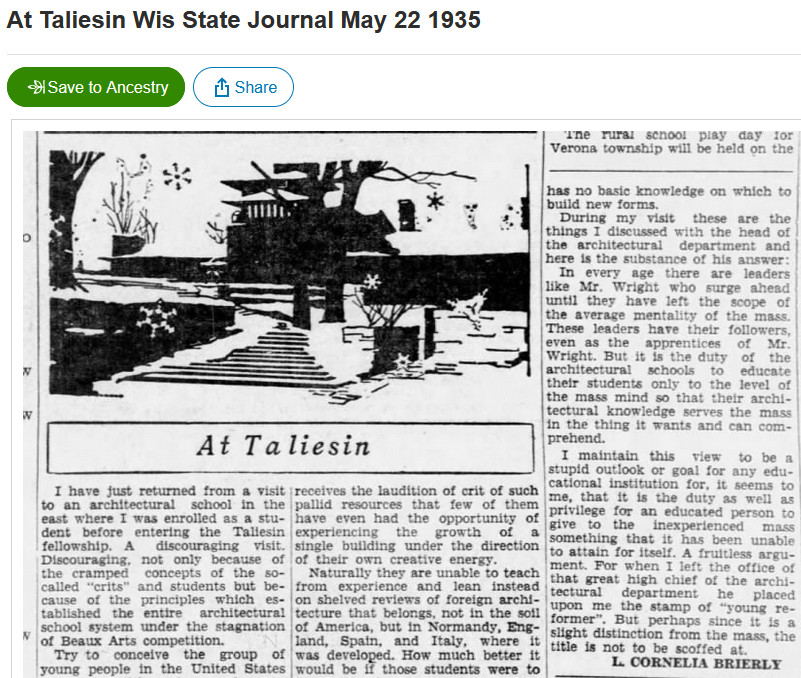

That’s just a year younger than architect Cornelia Brierly when she wrote this “At Taliesin” article in May, 1935:

The whole article is on p. 125-127 of the “At Taliesin” book.

Secondly,

the book is a source about the life and culture of the Taliesin Fellowship. The authors wrote about things going on at Taliesin, but also, as Cornelia did, they relayed their thoughts on new ideas.

Most of the articles

end with a listing of movies that were to be shown at the Hillside Playhouse to the public on the coming Sunday afternoon. Because the “At Taliesin” articles weren’t just philosophical treatises: they were a bid by the Fellowship to entice an audience to come out and pay 50 cents for a movie and cup of coffee.1

The articles also gave weekly updates on building activities at Taliesin.

The July 4, 1935 article

tells you construction they did at Taliesin:

Fortunately, Taliesin is in an ever state of change. Walls are being extended and new floors are being laid to accommodate our musical friends. We are trying out the new concrete mixer – which marks a new day in our building activities.

Edgar Tafel. “At Taliesin”, p. 140.

I wrote about this change in my post, “Preservation by distribution“.

Thirdly:

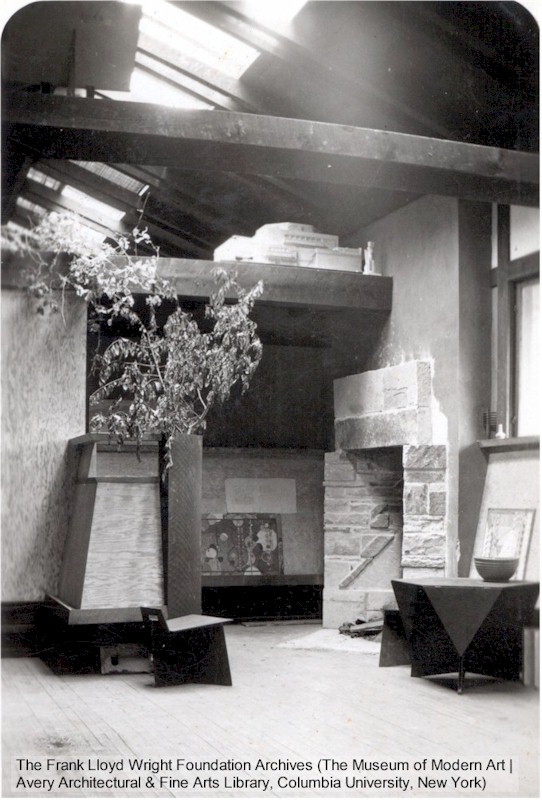

The book has 38 fantastic photographs. Like the one below:

This is the fireplace in the Dana Gallery at Hillside. The photo is on page 201 of the “At Taliesin” book. I put this image in my post, “Truth Hiding in Plain Sight“.

and 20 drawings:

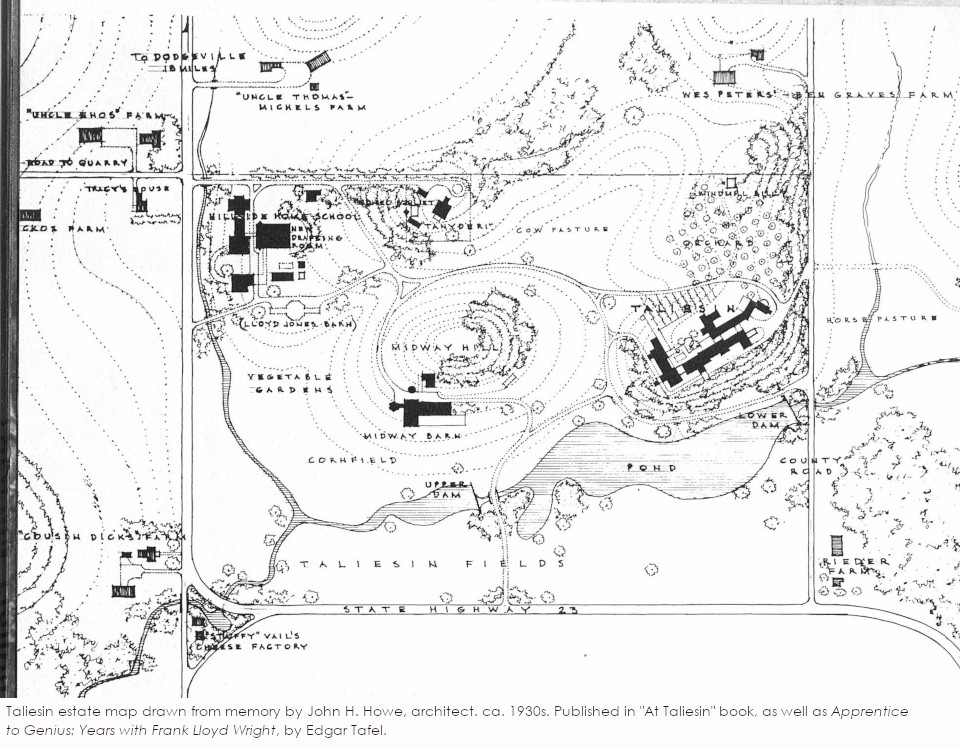

The image above comes from 154 of Apprentice to Genius because I couldn’t get a good copy of the one on pages 6-7 from the “At Taliesin” book.

In addition, the “At Taliesin” book has 31 articles by Frank Lloyd Wright. In one, he

actually

compliments someone else’s architecture!2

Wright wrote in the August 9, 1935 article that:

…. In their jail and courthouse Pittsburghers own a masterpiece of architecture. A great American architect H.H. Richardson of Boston built the building. He was a big man in every way and his bigness was of a kind that not only marks a distinct epoch in American architecture but commands the respect of the civilized world.

Frank Lloyd Wright. “At Taliesin”, p. 149.

In addition,

Henning wrote overviews for each year that the Fellowship wrote articles: 1934 to 1937. In the introductions to these chapters, he describes what was going on with the group, Frank Lloyd Wright, and the world at large.

Plus

Henning included articles about Taliesin written in the 1930s by professional writers. These writers came from the newspapers in Madison. They were invited out to Taliesin on the weekends. One writer, Betty Cass3 wrote about the “affair of the stringed instruments”. The article is a silly (true) story staring Wright and his wife, Olgivanna.

In it, Olgivanna watches as her husband keeps leaving the living room and coming back in with larger stringed instruments that have been delivered to Taliesin. They’ve obviously cost more and more money, but Olgivanna, helpless, watches as he comes back with them.

The last one is a bass viola. This was, Cass writes, “larger than he was, a regular Paul Bunyan of an instrument.” And Wright is mostly obscured behind it with “just twinkling eyes just peeking over the shiny brown side of the giant he was trying to strum.” “At Taliesin”, p. 308.

At that point, the humor of all of it got to Olgivanna, who started laughing so much that she cried.

First published July 11, 2023.

The graphic at the top of this post is used courtesy of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural and Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

Notes:

1. I’m not going to reel off all the movies. Read the book if you want to see them! – you could binge them…

we’ll call it “Fringing”

(y’know: binging on movies seen by Frank Lloyd Wright).

Check out how Wright ended his penned article on August 9, 1935:

We are happy to announce the extraordinary program to be presented at the Playhouse this Sunday, Aug. 11.

Four films, of such importance and such different character, will form one of the most significant and delightful performances ever presented at the Playhouse.

Le Million, one of the best films by the greatest French director, Rene Clair,–no film made, unless it be another by this same director, has integrated sound and movement more beautifully;

A Dog’s Life, an early and rare film, one of the few remaining made by Charlie Chaplin;

Orphan’s Benefit, the funniest of all the 30 or more Disneys we have seen;

Czar Duranday, a wonderfully made Russian cartoon of a famous Russian fairy story.

Three of these films have been chosen from the finest we have seen during the past two years at the Playhouse. Don’t miss this “picnic” next Sunday at three if you want to enjoy a hilariously entertaining afternoon.

“At Taliesin”, August 9, 1935. In the “At Taliesin” book, 150-151.

2. I know, I know: Wright insulting other people’s architecture. Most of us Frankophiles are aware of the man’s many traits, but some people really think he was an S.O.B.

3. Betty Cass is related to Bob Willoughby. He and I both worked at Taliesin Preservation and he read to us one winter at Taliesin.