Photograph of future architect (then apprentice) John Lautner (1911-1994) and wife Mary Faustina Roberts Lautner (“Marybud”, 1913-1995) standing at the southwest corner of Taliesin’s hill crown. Behind them is the chimney that served the dining rooms of the Taliesin Fellowship and the Wrights. I wrote about this space, here. The photo was taken by apprentice and later architect, Hank Schubart (1916-1998).

This is going to be a cat-themed post. But it does have a connection to Frank Lloyd Wright, I swear!

Let me explain….

Here are my cats, Wes and Gene:

This is a photo of them lying on the kitchen floor. My husband says they’re competing in the synchronized cat napping nationals.

Now, the names “Wes” and “Gene” are related to Frank Lloyd Wright and Taliesin. But I was not completely in charge of them being named Wes and Gene.

— well, ok, yes, actually, I was, since I was the one who first decided to name them that.

However —

I was not the person who focused my attention on names related to Taliesin.

You see,

in 2015, 5 kittens showed up on the Taliesin estate. Cats aren’t there all the time, but they do (and can) show up. Sometimes they are owned by residents at Taliesin. Or, sometimes they take up residence. At least one of these cats became internationally famous.

In fact,

anyone who took a tour at Taliesin starting in the late 1990s up to the twenty-teens met this cat. She was a long-haired calico named Sherpa.

Sherpa laying on a stone wall outside of the old Taliesin Fellowship dining room (it functions currently as an office and sometimes a guest room).

Sherpa appeared in the Taliesin tour program in the late 1990s. She lived at the Hillside structure and had one litter of kittens that delighted visitors.

the summer at Hillside with Sherpa and her kittens meant lots of real-time lessons on working with animals. There was no way you could talk about Wright’s history or ideas when there were 3 or 4 adorable kittens playing and jumping over each other on the deck at the edge of Hillside’s dining room (a photo of the deck is in a photo at Flickr, here).

After the season’s end, Sherpa was caught and spayed. By this time, she already walked in front of several tours at Taliesin, so she was given the name Sherpa. Since the Taliesin estate was basically her home, she settled in closer to the Taliesin building and began to “lead tours” there.1

That was because she knew where the guides went on tours, so she would walk ahead of the guides and group.

She appeared on a magazine cover

after a group of Japanese architects took a tour. They were as delighted by Sherpa as by the architecture. So one photo they took of her ended up on the cover of a magazine, below:

Back to Wes and Gene:

I hadn’t known about the kittens until I mentioned the desire for cats to a coworker at Taliesin Preservation. I was searching for a home, and having cats was on the agenda. Then she asked, “did you hear about the Taliesin kittens?”

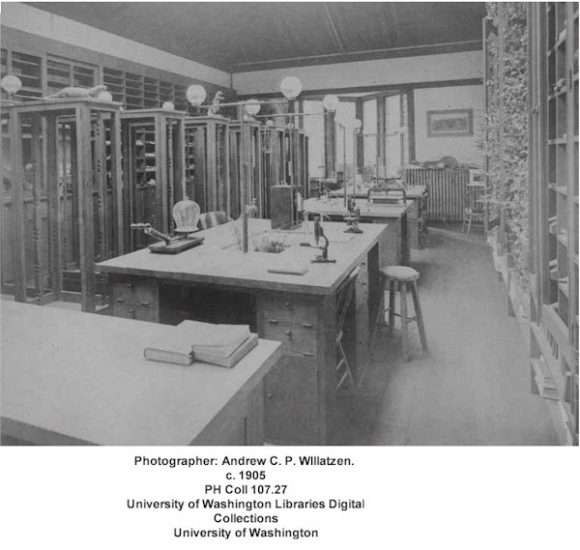

The kindle of five domestic shorthaired kittens had arrived in late spring. They were big enough to make themselves known to the students at the School of Architecture, who were then in session and living at Wright’s Hillside building.

Since they appeared on the Taliesin estate, my coworker, the students, and staff at the local vet clinic knew them as the “Taliesin kittens”. As I had already decided I wanted two male kittens, it took me less than 10 minutes to come up with the names Wes and Gene.

PLEASE NOTE: I decided immediately that I was NOT going to name them Frank and Lloyd, or Lloyd and Wright.

No, I’m not a cat lady! I’m just a Frankophile!

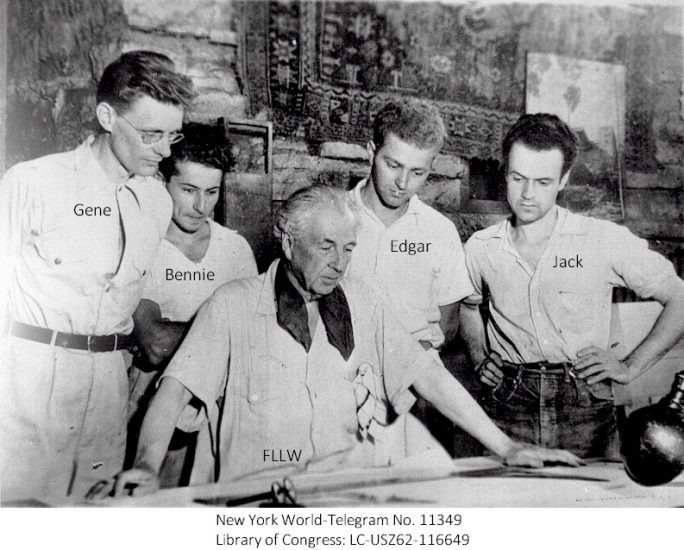

While I have not written on my blog about Wright’s son-in-law and engineer, Wes Peters, I did write about Gene Masselink last year.

Are they worthy of their names?

Wes is a little like Wes Peters, because he’s really big. But, while I love the guy, Gene is not worthy of the memory of Eugene Masselink.

And how did Wright feel about cats?

I don’t know.

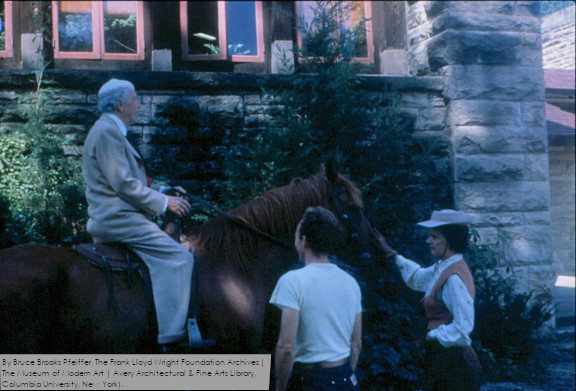

In fact, I don’t know how Wright felt about domesticated animals overall. Except for horses. He long admired them and rode them as long as he was able. The photograph below is Wright on a horse outside of the Hillside school building.2 The photo was taken in the 1950s.

Photograph of Wright on a horse to the east of the Assembly Hall at the Hillside Home School. Olgivanna Lloyd Wright stands on the right and apprentice, Joe Fabris, is wearing the t-shirt.

However, there is the doghouse:

That’s right: in 1956, 12-year-old Jim Berger wrote Frank Lloyd Wright. He was the son of clients Robert and Gloria Berger, who built their Wright house in San Anselmo, California. Jim asked Wright to design a home for their dog, Eddie. Jim would pay for the plans and materials through money he earned on his paper route. This link from the Smithsonian Magazine shows you the whole story, and Jim’s initial letter to Wright.

In addition,

Olgivanna Lloyd Wright liked dogs and you can find photos online of the Wrights sitting together outside at Taliesin West with her dog, Casanova. Casanova appears with Frank Lloyd Wright in the Garden Room (the living room) at Taliesin West. They’re on the webpage, “Five stylish men with dogs“.

First published February 8, 2023.

The photograph at the top of this post was taken by Hank Schubart and is in The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). Hank Schubert collection, 6501.0140.

Notes:

1 We used to do a 1 mile, all exterior Walking Tour. Sherpa would show up when we were with our groups on the road below Taliesin, and walk in front of us to Hillside. She would hang out at Hillside until the Walking tour came by in the afternoon. Then she would lead the later tour back to Taliesin, where the tours began.

2 This link shows you 94-year-old Joe Fabris at Wright’s Price Tower in Bartlesville, OK. It gives you a nice overview of that space. Joe is seen speaking to the Price Tower curator of Collections and Exhibitions (Hi, Scott!).