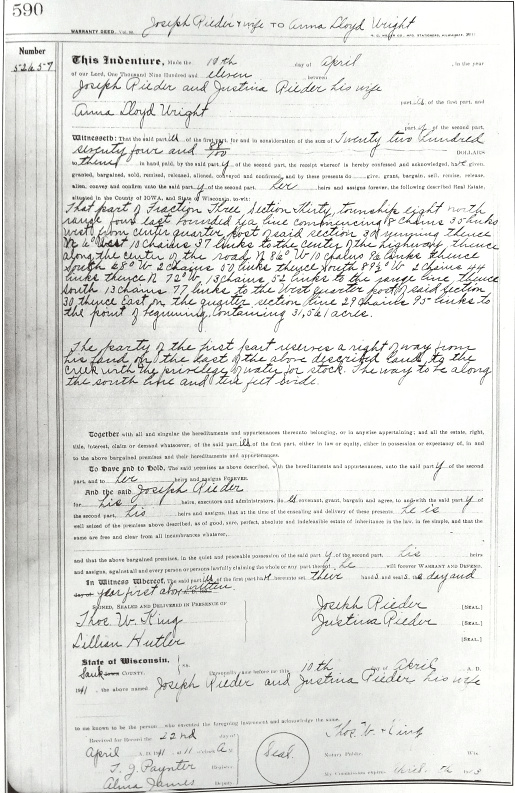

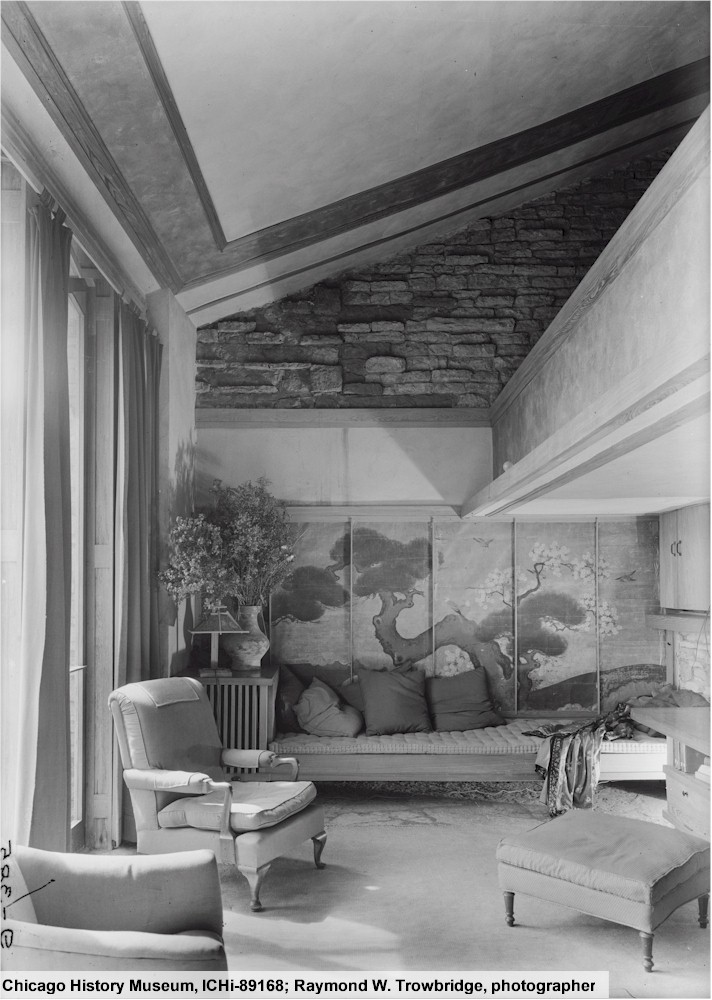

Reading Time: 6 minutes1930 photo looking south in Taliesin’s Loggia. Notice the vertical water stain on the horizontal band of plaster in the background.

Many photos taken inside Taliesin during Wright’s lifetime show water stains. That’s why I’m showing this photograph by Raymond Trowbridge again: it shows Taliesin’s Loggia with a vertical water stain in the background. Personally, I’ve never seen that part of the roof leaking, but I have seen water coming into Taliesin. I start this post with scary water, then give you a short version of what the Preservation Crew did about that (that jumps over a bit of the story), which changed into an even bigger fix.

That can happen with historic preservation. One problem can highlight other problems. It was overwhelming even though I didn’t work on the Preservation Crew – I just researched Taliesin’s history!

Regardless, the way to approach preservation at Taliesin is how you “eat an elephant“: sometimes it’s just best to go after the smaller things until the resources are there to complete the project.

Here’s (most of) my part in the story:

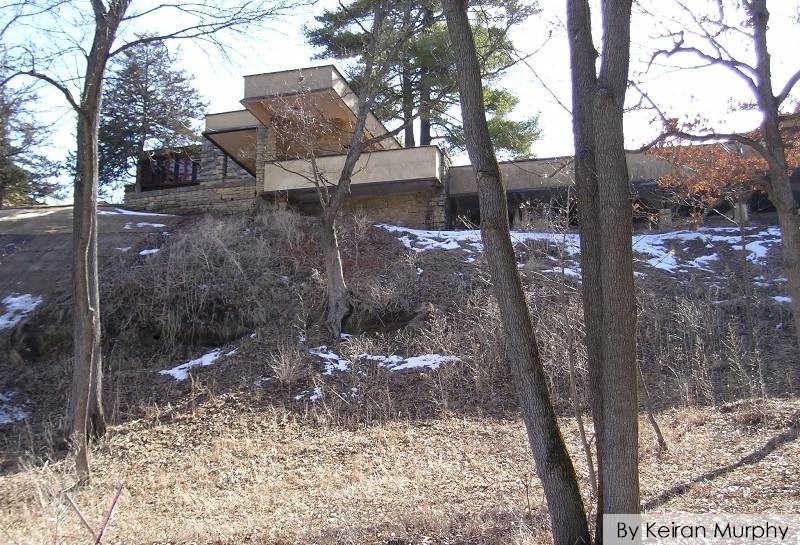

I was eating lunch in Olgivanna Lloyd Wright‘s bedroom one summer day. I worked as a Taliesin House Steward one-day-a-week at that time, and Olgivanna’s Bedroom wasn’t yet on tours. So it was nice to take a break there. As I watched a summer downpour, I looked out the windows onto the Loggia Terrace (here in a recent photo from Flickr). While the roof didn’t (doesn’t) leak, I watched as buckets of water poured into the space between a stone half-wall on the terrace, and the wall that it leaned away from.

Wright added the half-wall in the 1950s, so it wasn’t attached to the taller stone wall behind it.

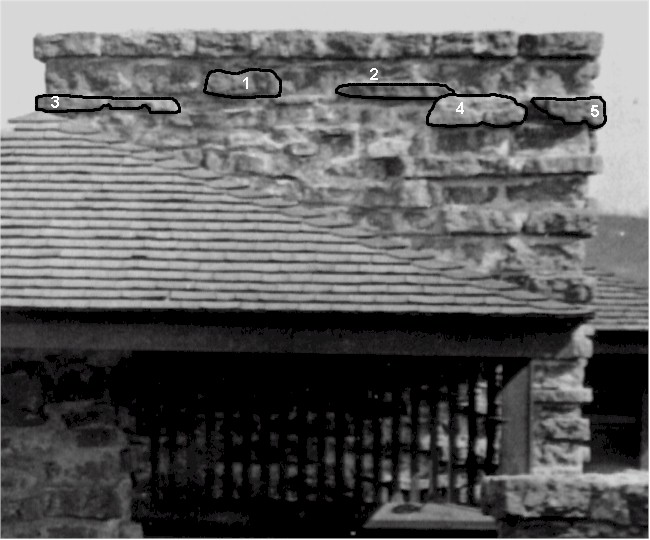

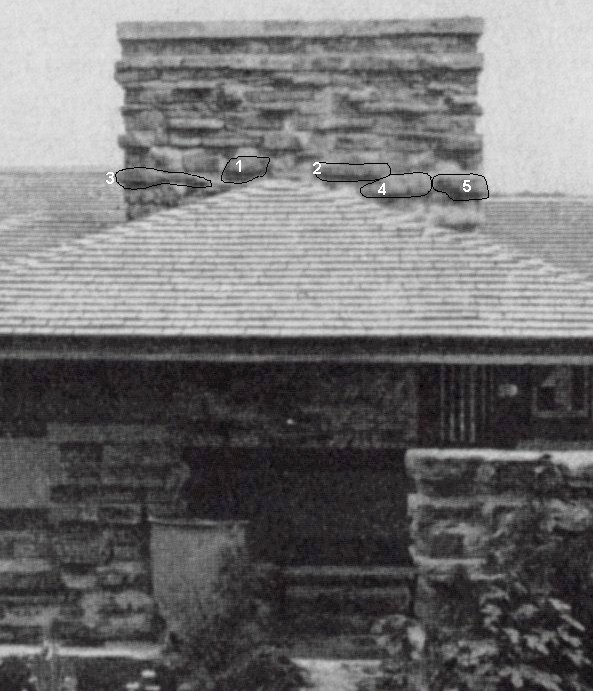

Check out the photo below to see this noticeable crack:

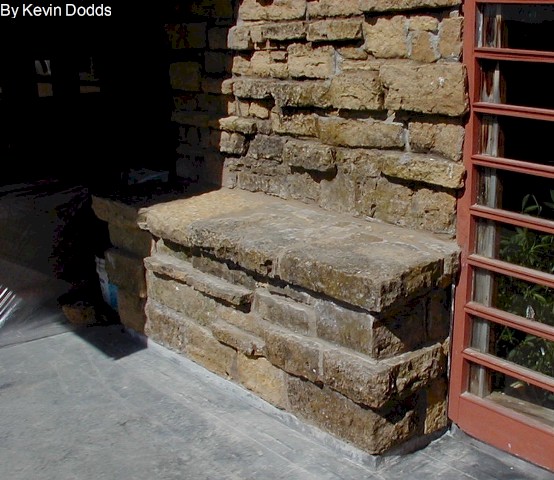

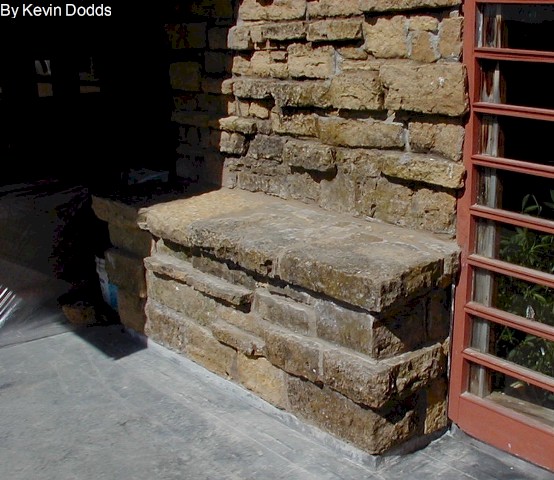

Taken on the Loggia Terrace. The red framed windows at Olgivanna Lloyd Wright’s Bedroom are in the background.

Kevin Dodds took this photograph in November, 2002.

Remember I wrote about how Wright buildings are smaller than you think? That’s not true here: that crack is as big as it looks.

As I stood there in Olgivanna’s bedroom, I tried not to think about how much water was pouring into the building, and where it was going. I didn’t have the resources to do anything about the problem, and worrying would drive me crazy.

Fortunately, the Preservation Crew did do something.

In fact, they started doing something right after that photo above was taken. Kevin, a Preservation Crew member, photographed this in the beginning of their work.

They took the pier apart, looking into the building. On the other side of that stone wall above, they saw that the hearth at Olgivanna Lloyd Wright’s Bedroom fireplace was deflecting. To fix the hearth, the Preservation Crew went under the building.

Why?

They had to support the hearth. But they didn’t want to support it on the floor below, in “the Gold Room”.1 They had to go into the crawlspace under the Gold Room to create support for its floor.

But, see, after its second fire Wright rebuilt Taliesin on the ashes of Taliesin II. So this crawlspace was a mess. The man who spearheaded the project2 explained it to me.

Imagine it:

Wright had recently spent over eight years of his life on a consuming project (the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo), and had acquired tons of art. That he brought home. And just under three years later his living quarters were, once again, consumed by fire.3

Wright wrote in his autobiography about that fire’s aftermath:

Left to me out of most of my earnings, since Taliesin I was destroyed, all I could show for my work and wanderings in the Orient for years past, were the leather trousers, burned socks, and shirt in which I stood, defeated, and what the workshop contained.

But Taliesin lived wherever I stood! A figure crept forward from out the shadows to say this to me. And I believed what Olgivanna said.

Frank Lloyd Wright, An Autobiography (Duell, Sloan and Pearce, New York, 1943), 262.

So, Wright moved on. Because what else was he going to do? Therefore, when the Preservation Crew (really, two men) started work, the crawlspace was full of dirt and ash. Literally: the ashes from the Taliesin II fire.

This photo shows the crawlspace.

It was taken a month after that photo showing the stone pier on the Loggia Terrace:

Photograph taken in December, 2002, by Kevin Dodds.

The “after” photo is below.

Kevin took this after the debris and ash (but NOT the stone piers) were removed. Then they built a support for the vertical section they built in the floor above:

Photograph in Taliesin’s crawlspace taken in February, 2003 by Kevin Dodds.

With that, they were able to put the structure in the Gold Room to support the hearth in Olgivanna’s Bedroom.

The support in the Gold Room.

This structure supported the stone hearth at Olgivanna Lloyd Wright’s fireplace:

Photograph looking north in the room at Taliesin known as “the Gold Room”. Taken March 2004, by Kevin Dodds.

With that, they left it alone until they could get back to it.

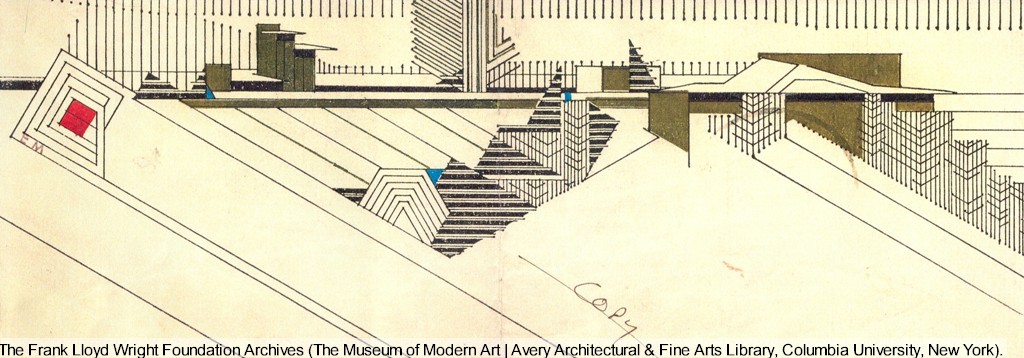

In 2004, a year after this work, students from the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture (now The School of Architecture), working under the direction of the Preservation Crew, repaired the terrace outside of Olgivanna Lloyd Wright’s Bedroom (that’s the light blue area you see in the the first photo of the half-wall).

In 2005, the half-wall was rebuilt

Here’s a photo of the pier, rebuilt (with two layers of flashing):

Photograph by Kevin Dodds taken May 2005. Looking southwest at the rebuilt half-wall on the Loggia Terrace. The dark membrane at the bottom of the photograph is waterproofing. This was covered by flagstone once the Loggia Terrace was restored.

In 2006, the crew continued in the crawlspace

After creating wooden forms, they prepared to pour concrete piers in it. Here’s one photo I took:

I wasn’t usually involved with this stuff. But I had to get out and see the pumper truck. That photo above is showing the arm bring the concrete in. They brought it in through a little passageway (out of sight on the photograph’s left side). The passageway goes to the crawlspace where the forms were set for the concrete pour.

The concrete supports were created and set.

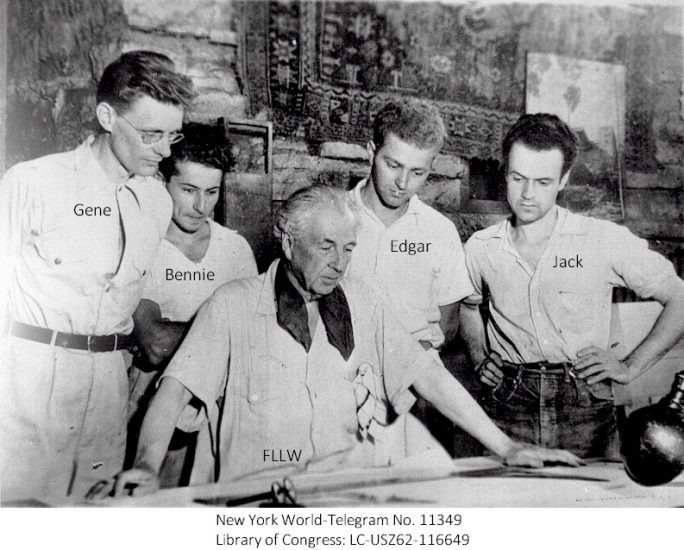

When that was done, they put jacks on top of them, then devised a way to bring steel beams into the crawlspace. It’s cool: hollow, rectangular, steel pieces were about two feet long were brought in, then bolted together.

Jacks supporting the beams in the crawlspace that the Preservation Crew had constructed and prepared. Photograph taken March 2007 by Kevin Dodds.

The crawlspace looked like this for awhile.

The Preservation Crew had to wait until the next phase: jacking up the beams to correct the deflection.

Once this was accomplished, they contracted with Custom Metals (Madison, WI) to permanently weld the steel I-beams in the crawlspace.

Photos that show welding are so cinematic!

Taken by Kevin Dodds in February, 2010.

Photograph of the metal posts, beams, and concrete pads in Taliesin’s crawlspace. Taken February, 2010 by Kevin Dodds.

Once this was settled, they worked upstairs.

The Preservation Crew restored Olgivanna’s Bedroom in 2010. The bedroom was prepped and put on Taliesin House tours.

In 2011, Taliesin turned 100 years old.

After the tour season finished that year, the Preservation Crew began to completely restore Taliesin’s Loggia. After this, they restored all of the spaces in Taliesin’s Guest Wing rooms.

So now the Guest Wing is level, warmer, doesn’t smell like mildew, and the crew rebuilt amazing pieces of furniture. While you can’t see the crawlspace on a tour, you can go on a Virtual Tour through Taliesin’s Guest Wing (via Facebook), here.

When I look back on these things, I’m a little amazed. And I was only the sidelines for most of it!

Published August 31, 2021

The photograph at the top of this post is by Raymond C. Trowbridge at the Chicago History Museum, ICHi-89168. It is in the public domain.

Thanks to Kevin Dodds and Ryan Hewson from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation for allowing me to publish the work photographs.

1 It’s unknown why the room was given that name. Taliesin Preservation asked members of the Taliesin community (members of the Taliesin Fellowship) why it was given that name and the people they asked didn’t know.

2 Jim, the former Estate Manager who brought me to the crawlspace, is written about here.

3 This was an electrical fire.