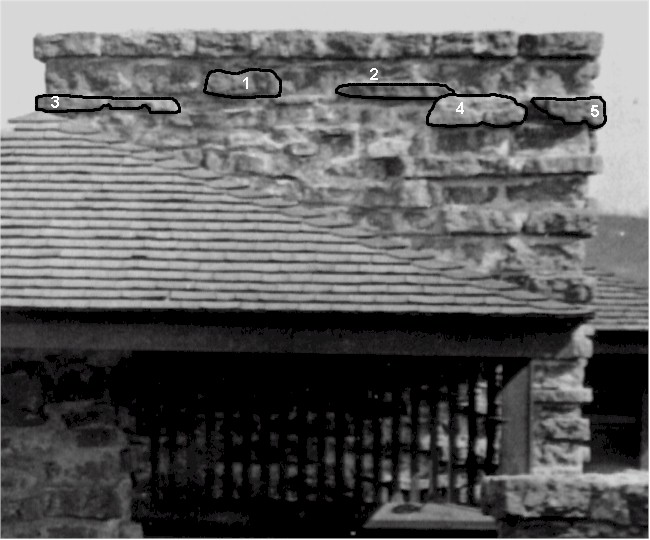

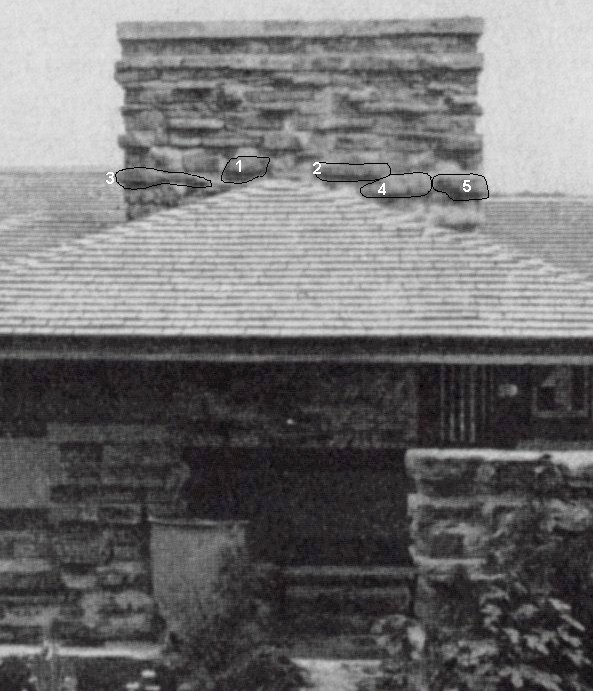

Looking west in the Drafting Studio that Wright used at Taliesin until World War II (after that he used it as an office). His desk is on the right-hand side. If you look at the ascending stairs, you see two lines: one that is horizontal, and another that’s vertical. These are remnants from a change that occurred at the stone.

As I wrote in “I looked at stone“, the masonry used in Taliesin’s piers, walls, and floors often holds evidence of the building changes. So this post is going to be about two changes at Taliesin that are also visible in its stone. In this case, both of these can be seen in Taliesin’s Drafting Studio.

So, what are these changes?

Evidence of one change is on the west side of the room, and evidence of one is by the room’s doorway. I’ll write about the evidence seen in the stone because I hope they will stay there.1 Particularly because one of the changes is the only sign that something was there when Wright was alive. So I really hope no one touches it. That change is by the door on the east wall of the Drafting Studio.

First, though

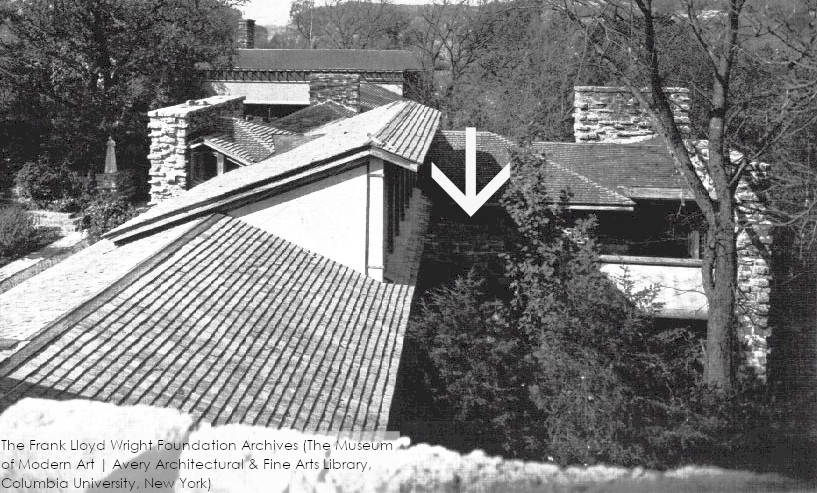

There’s a sign of a change that stands on the outside of Taliesin’s vault that I want to talk about. That change can be seen in the photo at the top of this post, which shows the vault on the room’s west side. It’s by the steps that go up to the top of the vault.

Vault? wth are you talking about: I don’t see a metal door on this “vault” you’re talking about. You’re hallucinating.

Oh, sorry [she says to her cranky-alter-ego]: the stone you see is around a bank vault that is on the edge of the room. In Taliesin’s studio you’re looking at the back of the vault. You get into the vault through a bank door on the other side. btw: The steps don’t bring you into the vault.

Wright didn’t plan on using the top of the vault, because most of the vault was originally outside.

Ok, I’m getting ahead of myself

Let’s go back to the lines on the stone.

The change on the stone is the two lines to the right of the steps: a horizontal line and a vertical line. There aren’t any known photos or drawings that show the room’s configuration in the area to show exactly what wall caused those lines. But the lines would have been created in the ‘teens to the early ’20s. Looking at the lines though, I think they were made because a plaster wall/walls terminated at that spot on the vault.

Hold on – I’ll take you back in Taliesin’s history:

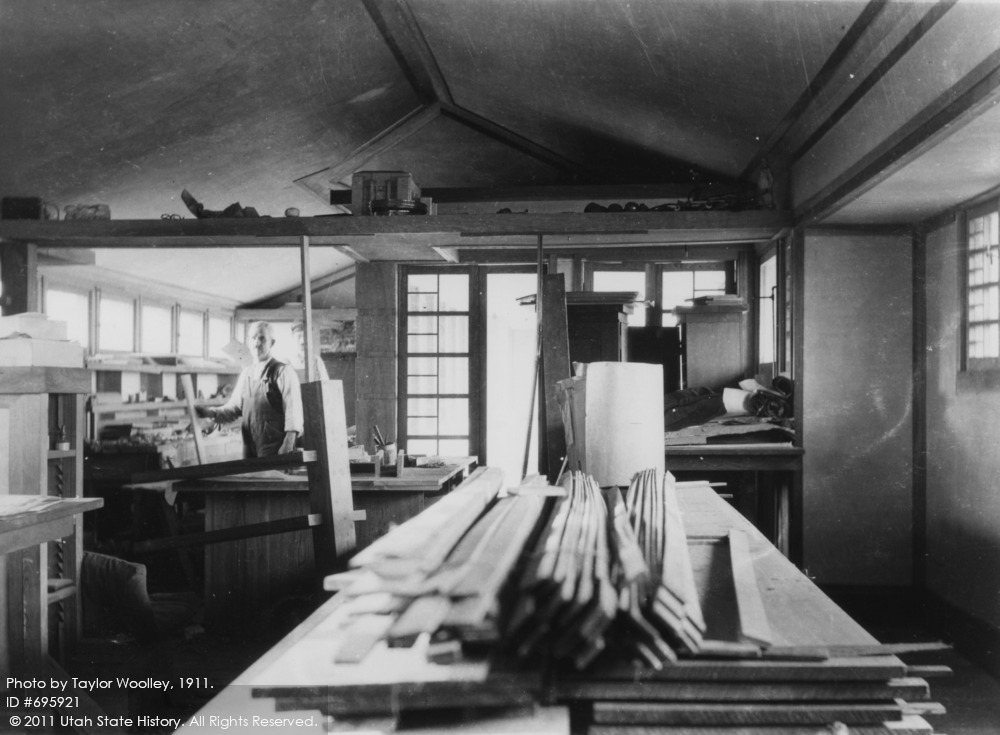

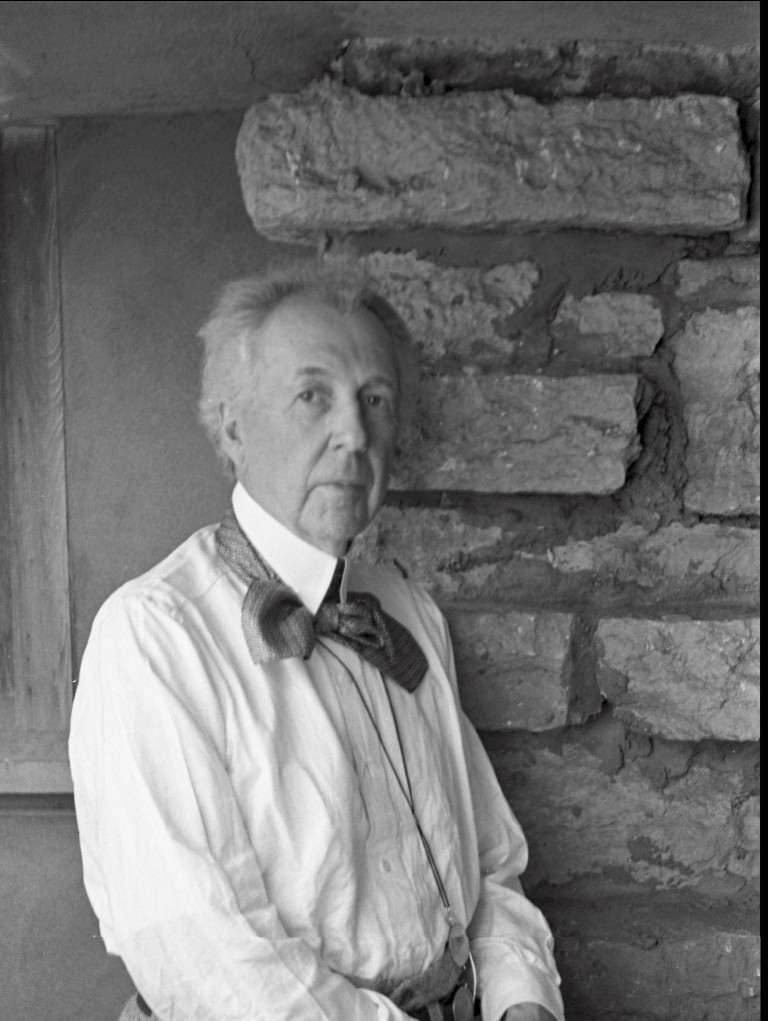

The photo below was taken when Wright first built the studio in 1911. So the vault wasn’t there. But you get a sense of how the west side of the room ended and that might help to visualize what terminated in the vault that was added later.

At the time the photo was taken, the studio was a rectangular room with a gable roof. The side of the room where the vault will eventually show up is on the right hand side in this one photo from the Taliesin I era. That photo was taken by Wright’s draftsman, Taylor Woolley:

Woolley took this 1911 photo looking west in the Taliesin drafting studio. When the room was finished, Wright put the drafting tables to Wooley’s left, as well as where he was standing, and behind him (you can see the other view of the studio in this photo). The two men in the background of this photo are unidentified.

Can you tell us what we’re seeing?

From what I can figure, Taylor Woolley was standing about where the lamp is in the photograph at the top of this post. You can see the building is close to being finished, because of the trim on the ceiling, but there’s still more that’s laid on the table in the foreground.

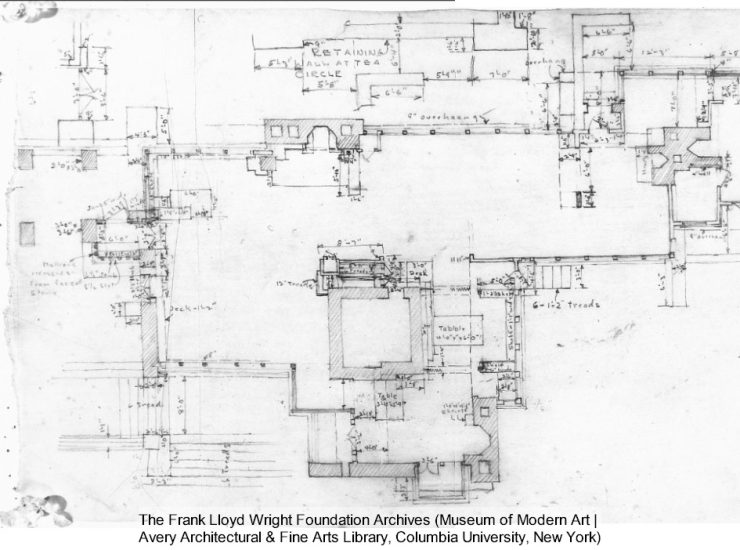

Wright scholar, Sidney Robinson, pointed out that the vault was probably built by 1913.2 That’s because there’s a drawing that was published that year that shows it. It’s drawing number 1403.011. If you click the link go to see the drawing online, they tell you it’s a 1914 drawing. But they’re wrong. The drawing was published in Western Architect 1913.2

And, oh sh*t – that means I’ve got to use a fricking drawing to try to prove something, and I’m always like, “don’t trust the drawings“…. OK: Let’s say we CAN’T prove that the damned vault was there in 1913, but it showed up in a PHOTO at least.

Standing on the top of Taliesin’s Living Room roof by its chimney, looking west. Taliesin’s Drafting Studio is to the left of the arrow, the vault under the arrow, and Wright’s private office to the right of the arrow. I know this was published in Frank Lloyd Wright: Man In Possession of His Earth, which was put out by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 1962, so that’s who I think owns the photo, but I’m not sure.

Based on details, this photo was taken between 1918-1921. Wright expanded the studio before Taliesin’s second fire, and so the vault was then inside.

ANYHOW,

The marks on the stone outside of the Vault come from its changes. Luckily the marks have stayed there, unmolested.

Additionally,

on the opposite side of this room, there’s another mark on the stone. This is on the stone column you walk by when you enter the studio. Here’s the room today. I put an arrow pointing at the column:

Looking east in Taliesin’s Drafting Studio. The column is where the Preservation Crew found a window during Taliesin’s Save America’s Treasures project in 2003-04.

Photograph by “Stilfehler”, on Wikimedia.org.

That column has a red and white vertical line you can see. It shows up in the photo I took below:

Looking east in the Taliesin Drafting Studio.

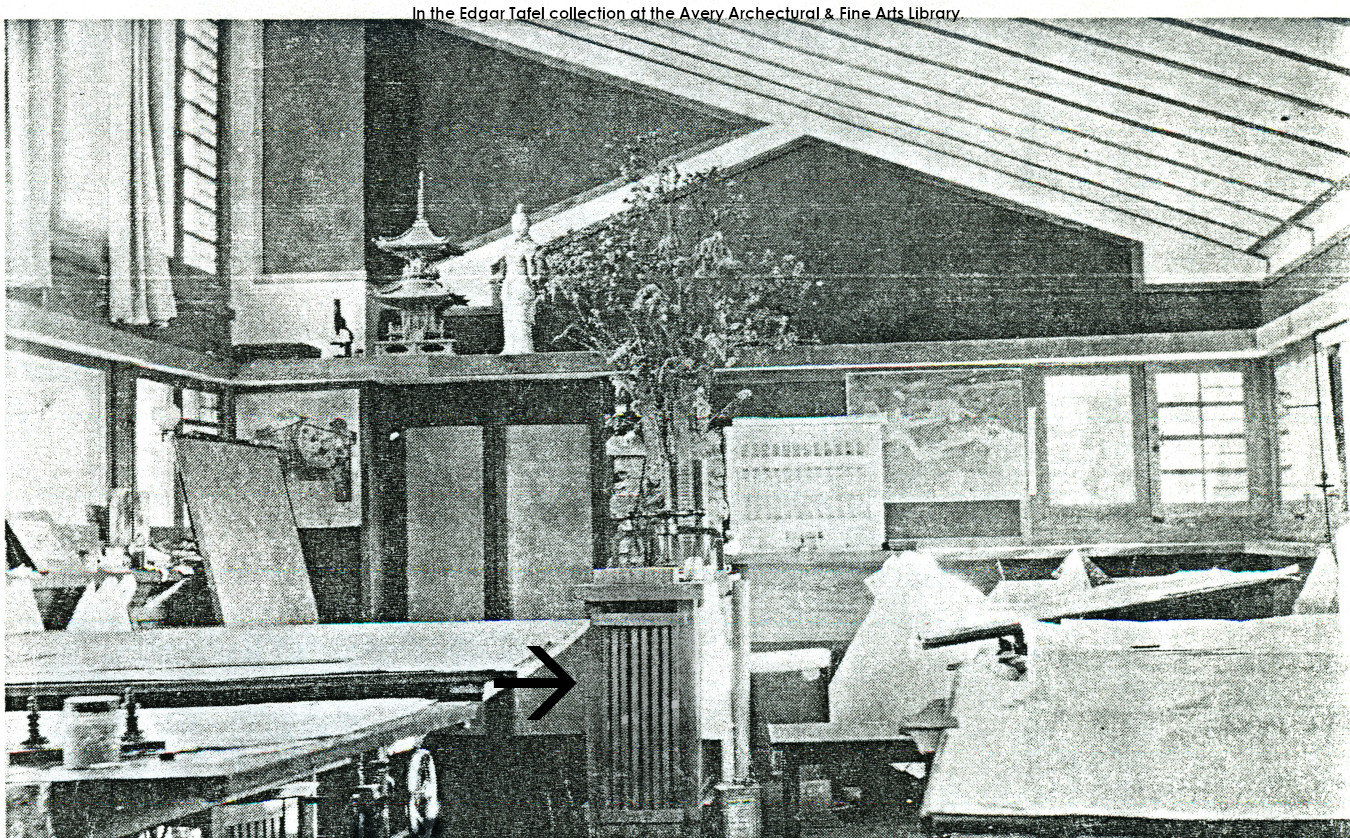

That red and white line is there because there a built-in radiator cover terminated at the column for decades. You can see that radiator in the studio back in to the Taliesin II era. Here’s a photo from 1917-18 that shows it:

This photograph is a postcard that Wright’s sister Maginel gave to Edgar Tafel. The photo is published in the book, About Wright: An Album of Recollections by Those Who Knew Frank Lloyd Wright, ed. Edgar Tafel. Looking east in the Taliesin Drafting Studio. The black arrow is pointing at the radiator cover.

The radiator cover shows up in photographs throughout Wright’s life.

Yet

the photos also show he changed it. Originally, the radiator was perpendicular to the stone column. Then he moved the radiator from perpendicular to, to parallel to, the east wall.

But he kept what looks like the first cover. Maybe he made it into a little cabinet. Because a little door, with a handle, appears on the old radiator cover in several photos from the mid-1950s. These are at the Wisconsin Historical Society, like this one below:

Photograph by George Stein. Stein took the photo in December 1955. Looking southeast in Taliesin’s Drafting Studio.

You can see the part of the old cover with the door and door handle next to the Monona Terrace model. And to the right of the cover, you see the top of the radiator, against the east wall. The photo taken in the ’50s. So, maybe the radiator cover that’s in the 1917-18 photo from Tafel’s book has been turned into a cabinet, maybe? As near as I can figure out, the former radiator cover (that became a cabinet?) was there when Wright died.

Or I think it was there.

That’s because I came across a photo of it years ago that showed the radiator cover, and the cabinet. The Chicago Tribune published that photo in 1962 [that’s (W)right, after his death], I bought it on Ebay3 and it’s below:

Looking east in the Taliesin Drafting Studio in 1962. The photo shows the radiator and Wright’s Asian art works.

There’s a note on the back of the photo saying “September 20, 1962”.

At some point that entire built-in was removed, along with that radiator. And the floor in this area, where the radiator had been, must have been removed/replaced, so you can’t see a sign that the piping was there. So the physical evidence on the floor is gone. And the only thing that remains (as far as I know and can remember from my time at Taliesin) is what’s on the stone column.

So, before I end this post, I’ll put in this request to those who might work on or restore the Taliesin Drafting Studio: don’t touch that stone!

First published, September 25, 2022.

I took the photograph at the top of this post in 2005…. And, despite what some might think, YES, he used that lamp on the desk!

Notes:

1 Not that I think people will chuck things out at Taliesin willy nilly, but sometimes stuff happens.

2 I don’t know where Wright got the vault itself. It’s fireproofed and must be heavy, but I never got the chance to do the research on where Wright acquired it.

3 Although I should say that Bruce Pfeiffer was wrong, since he’s the one who dated the drawings. Anyway, the drawing appears in the article was “Taliesin, the home of Frank Lloyd Wright, and a study of the owner,” by Charles Robert Ashbee, Western Architect, 19 (February 1913), 16-19.

4 There’s got to be some joke about historians prowling Ebay for things related to their obsessions.