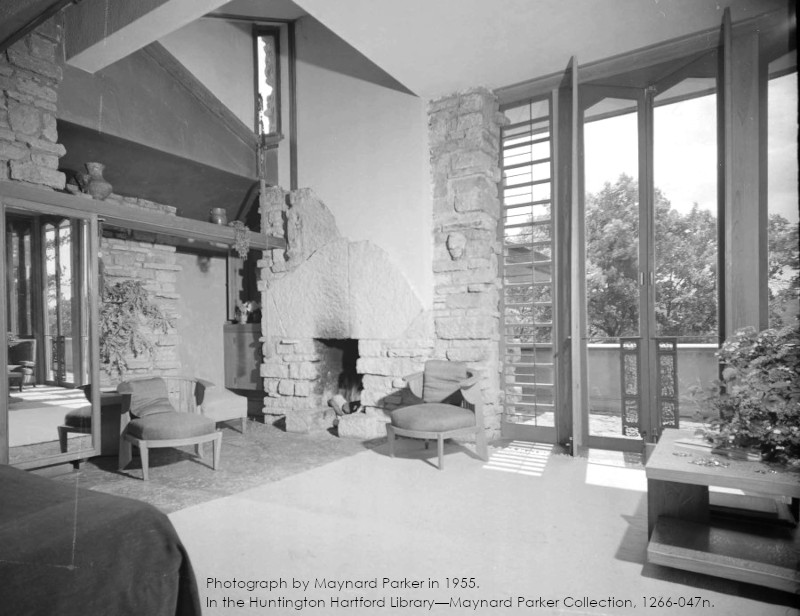

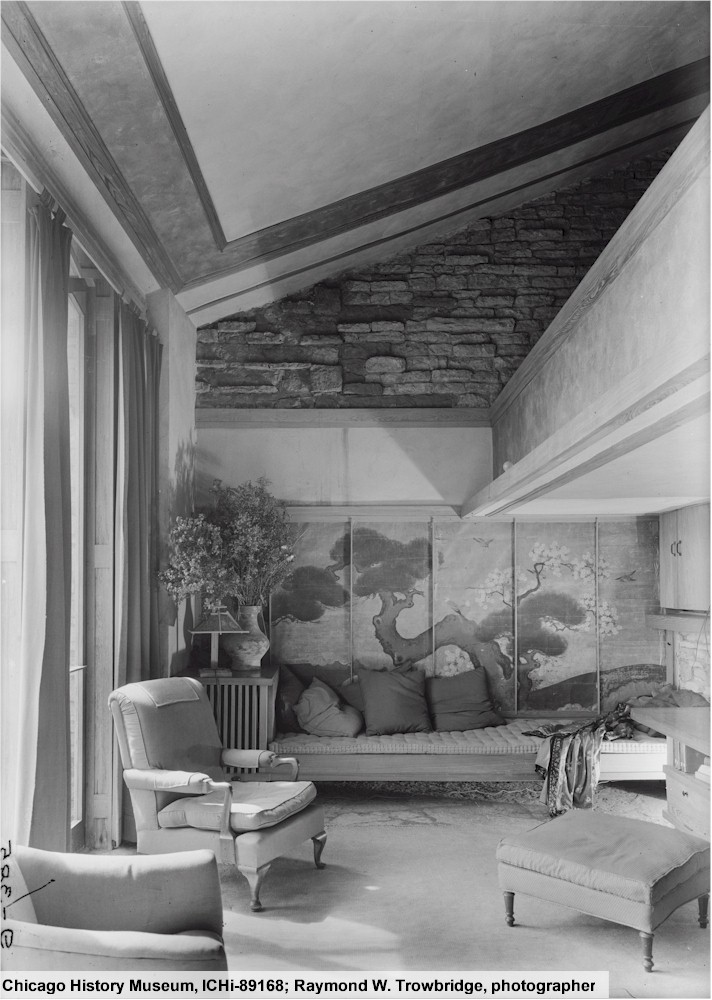

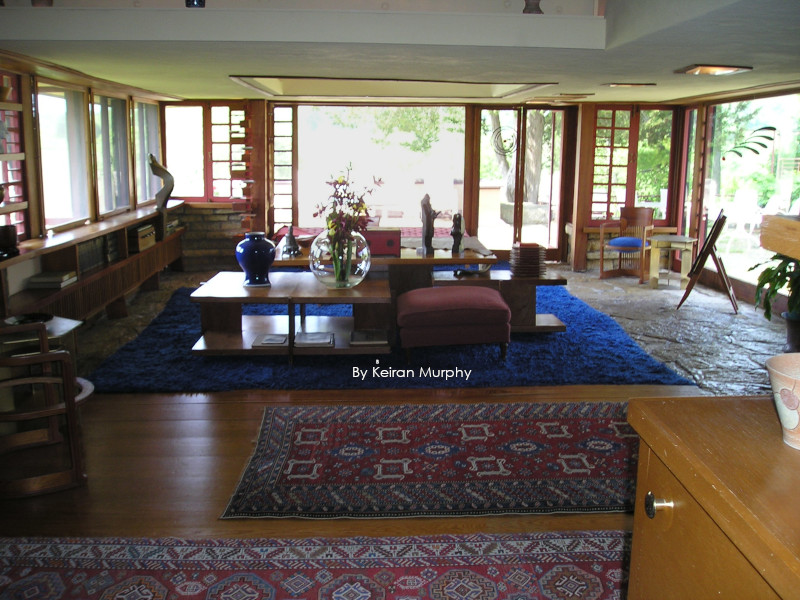

A photograph of Taliesin’s Living Room that I took during the first week of House Opening in 2006.

I opened the front door yesterday and stepped outside for a moment to experience rain coming down in 50F (10C) temps.

Due to this, I was pushed back into “House Opening”.

That is, I remembered the work on the buildings that Taliesin Preservation staff did from 1995-2014.

I mentioned this before in the posts, “Physical Taliesin History” and “Bats at Taliesin“

Why now?

Because we opened the House and Hillside in the second-half of April for every year from 1995 to 2013. Therefore, sometimes April’s sights, smells,

and the song “That’s the Way that the World Goes Round” [and others] by singer songwriter, John Prine,1

bring me back to all of those times of cleaning and preparing Taliesin and Hillside for the upcoming tour season.

Here’s the scene:

The gleam of House Opening usually began in late February. That’s when Tom W. (the Head Taliesin House Steward and collections person for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation) came into the office where I worked.

I worked in the room under the spire.

He approached me tentatively, and we reenacted a play we carried out each spring.

Tom would say

with a slight uptick in his voice, “So…, Keiran, what do you think about… “

then he would usually name the last two full weeks in April that we, and two other staff members, would open Taliesin.

I often groaned and then agreed.

Now, you might be thinking:

“But I’d adore being at Taliesin that much!! And being around all of those artifacts and furniture!!”

True.

But it was beauty at a price.

When we opened the buildings, we spent two weeks moving, sweeping, vacuuming, and window washing while sitting in unheated spaces with wooden and stone floors, single-pane glass windows, and plaster walls with no insulation.

We cleaned all of the furniture by hand with liquid Ivory soap and hot water that we put into buckets from the sink, which slowly cooled to room temperature (which in that case was, again, about 50F).

After six or seven hours, the cold sinks into your bones.

When we came back the next day, we had just a little less energy.

And then did this the day after that, and the day after that, etc., etc. ….

If you don’t believe

that this could be difficult, I’ll tell the story about this one man, J. Z.

He volunteered to help Opening for about 3 seasons. He always appeared in the second week when things were beginning to take on some order.

On these visits

He spent a lot of his time talking while staff cleaned, and drinking coffee in the one heated space of Taliesin’s Living Quarters (the Little Kitchen).

Then,

one day during Opening, Tom kept politely asking J.Z. to help with things.

I remember cleaning furniture with the others while Tom continuously said, “J., could come in here and help me with this?”

Tom’s effort kept J. busy that whole day. Which was also the last time I ever saw him.

Why the hell did I do Opening?

Because someone had to.

You’d think that office staff would, but while several Opened Hillside, I don’t think that for others that it was ever their thing. Plus, a lot of them were prepping for the season in other ways.

Although, in 2014, the Preservation Director at Taliesin worked on Opening, and I was surprised to see him every day.

That’s because, by that time I was used to other folks saying they really wanted to do it who only showed up for several days. Then they would get pulled away and never come back.

Additionally,

if we didn’t have consistent staff, it could be dangerous for the artifacts.

Particularly in the early years

when our opening of the buildings was a “learning by doing” operation.

We weren’t incompetent, but…

for example:

The first few seasons of House Opening included removing the black plastic sheets that Rud2 (the maintenance man for the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation) stapled onto the window mullions after we’d closed up the building the previous November.

Or, one time,

I stopped two staff members from dragging out a Chaise Lounge onto the Loggia Terrace to “let it get some sunshine”.

Or the time I walked past someone, not trained on things, violently shaking an original rug.

We eventually figured all of this out, but opening Taliesin was still a dirty, exhausting business.

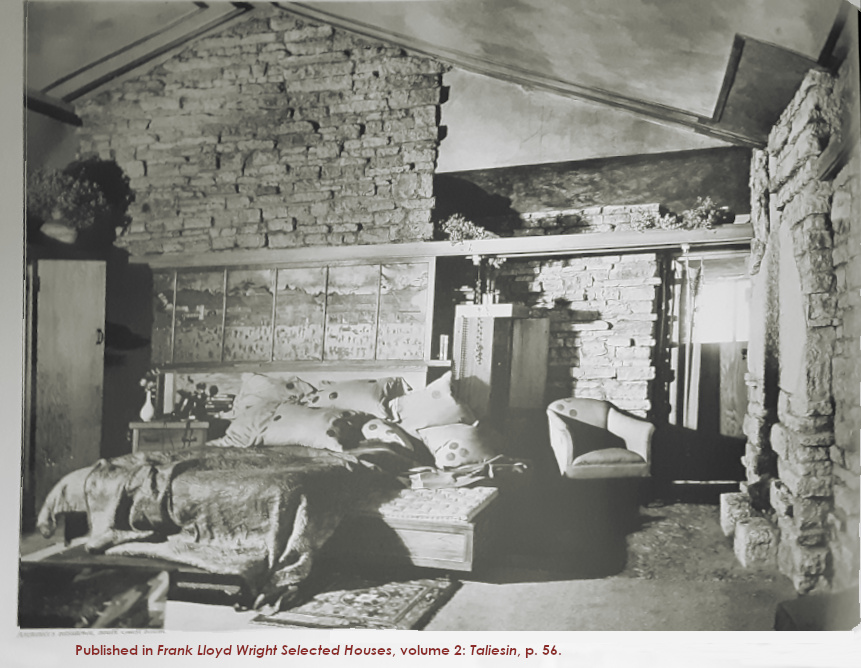

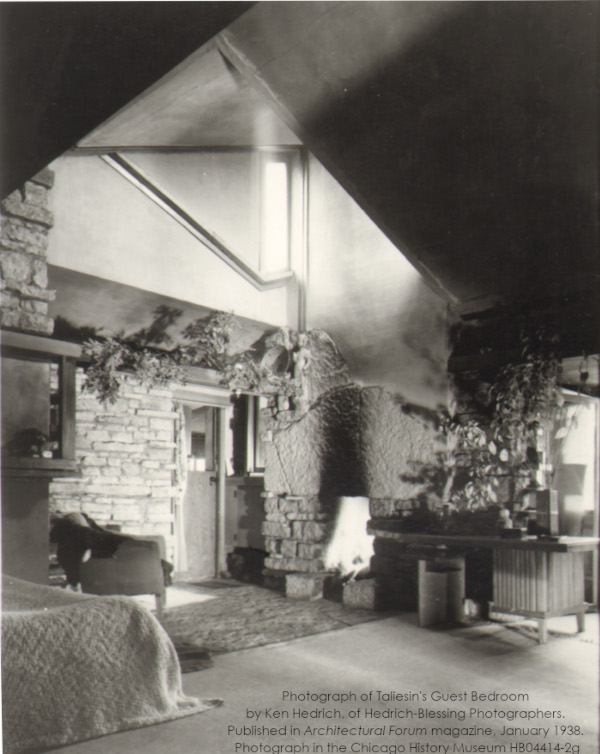

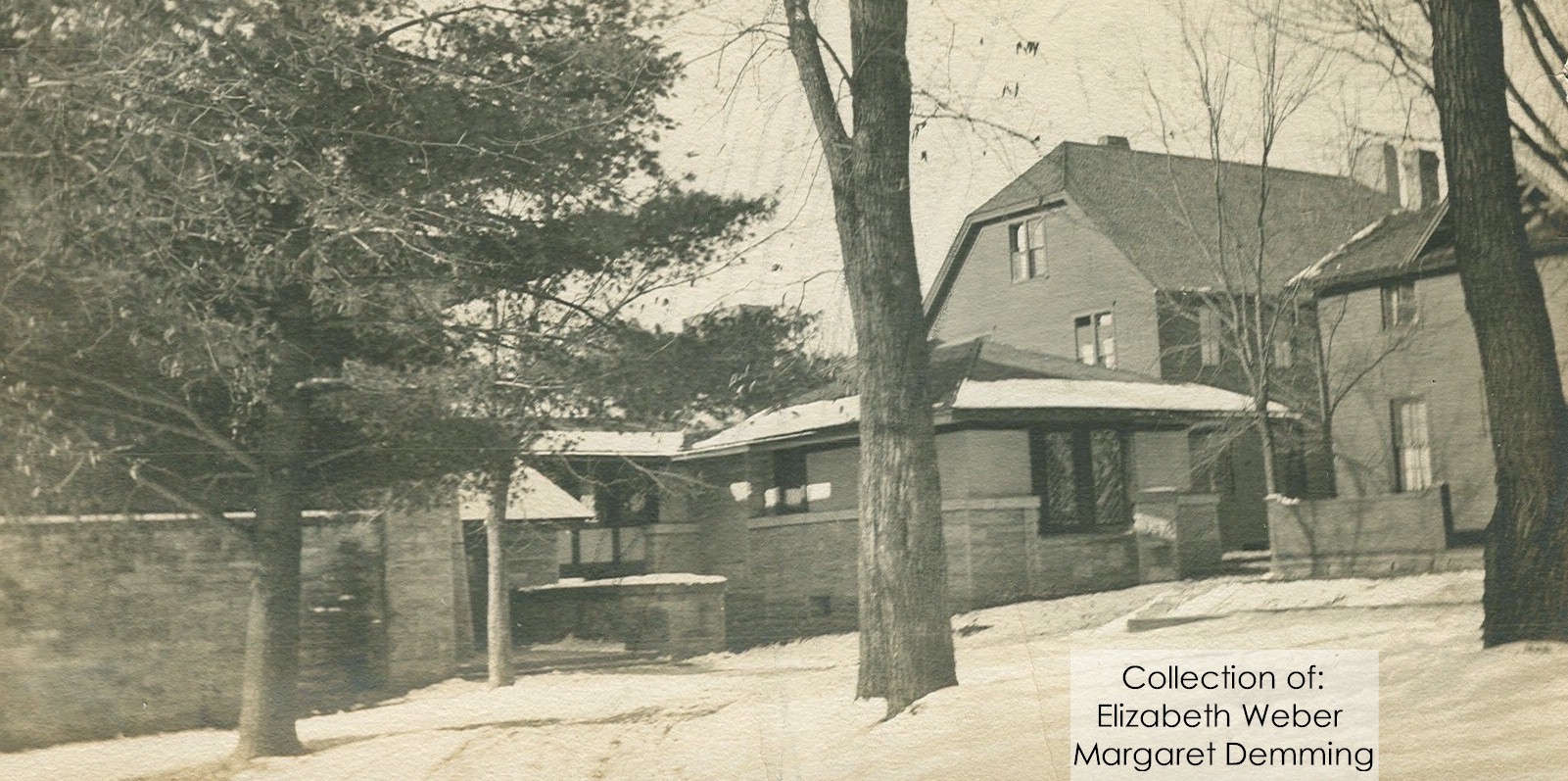

Here are two photos

That I took in Frank Lloyd Wright’s Bedroom. That was the first room we’d “open” each season.

Before:

Looking south in Wright’s study area at the beginning of Opening in April 2006.

And after:

Looking south in Wright’s bedroom in May 2006.

Opening of the buildings, fortunately, inspired a former supervisor to devise

Class Trips

before each season.

In the beginning, we paid our way. But then figured out reciprocal agreements, gas money reimbursements, and more.

Craig did this in order

- To educate staff;

- Get us excited for the season;

- Refresh our memories on the architect whose buildings we worked in;

- And hopefully guilt the staff (many who did this job part-time) to come in and open the building despite the cold, dirt, and exhaustion.

Class Trips Itinerary

eventually broke down this way: we’d meet at the Frank Lloyd Wright Visitor Center early in the morning, divide ourselves into cars with drivers, and carpool to a destination. Most of the trips were places we could drive to and from with a trip for lunch.

If you don’t want to see over a dozen Class Trips, click here.

The Class Trips got me to:

- Frank Lloyd Wright’s Home and Studio in Oak Park, Illinois and Unity Temple three times.

- The Johnson Wax Administration Building and the Johnson family home, Wingspread, I think also three times.

Remember we started this in 1995.

- One time to the Chicago Art Institute so we could see the exhibit on architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh

- That might have been the time we saw Wright’s remodel of the Rookery

Somewhere in there

- we saw the Robie House

and

Then

- we went to the Annunciation Greek Orthodox Church,

And maybe on that trip we also saw

- the Greenberg House (in Ottawa, which is in Eastern Wisconsin).

Because they’re about 35 miles away from each other.

We got into the Greenberg House because a staff member’s mother knew the owner, Maurice Greenberg, an original Wright client!

And

We saw

- the Heurtley House and

- the Hills-DeCaro House across the street

We got to these houses because the owners of the Heurtley house invited guide Margaret Ingraham. She contacted them and they consented to us all coming to their, and their neighbor’s, houses.

Others:

- “Cedar Rock“, the Walter House in Iowa,

- the Schwartz House in Two Rivers, WI,

- the Park Inn Hotel in Mason City, Iowa (thanks, Bob!). And I think we went to

- the Stockman House the same day.

And here’s the “and more” of the list

3 above-and-beyond trips due to the work of one of my supervisors.

Chris was evidently working with the idea of “go big or go home“

We went to:

- the Dana-Thomas House in Springfield, IL,

- And the next year, the Fabyan Villa (a Wright remodel) that was followed the next day by

- the Meyer May House in Grand Rapids, Michigan.

And, finally:

- Fallingwater and

- Kentuck Knob.

That last big trip was probably because Chris knew he couldn’t get away with it anymore.

The Class Trips took place before and after Fallingwater,3 but House Opening did eventually end.

The End of House Opening

In anticipation of getting heat back into the Living Quarters, I think March 2014 was the last time we opened.

After that we didn’t have to mini-mothball Taliesin every winter.

And Taliesin Preservation now has a Lead Custodian who takes care of the buildings.

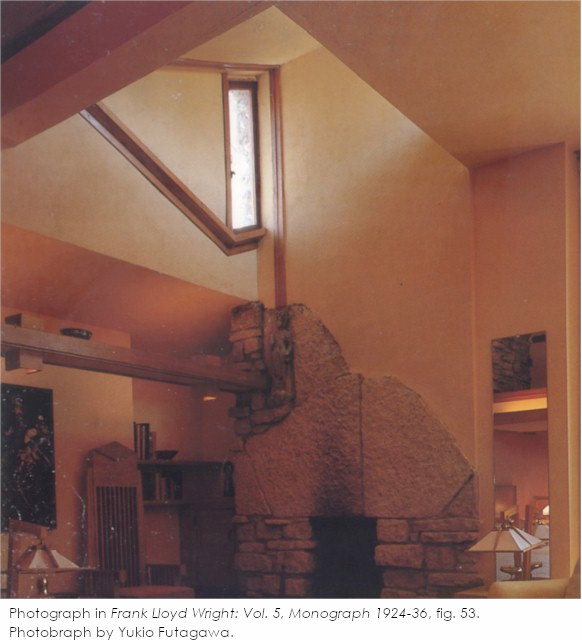

I should ask her if she’s ever straddled the top of a shelf on the northwest corner of the Garden Room to clean the wood up to the windows…. Or cleaned the batsh*t on the Loft in Taliesin’s Guest Bedroom.

Yet

For all my b*tching, I looked forward to two things during House Opening:

- The cookies that Tom W. brought in during the first week

(I think he got the cookies at the Cenex Station in Mount Horeb and they were fantastic).

- Getting to sit in Taliesin’s Living Room on the last day of Opening, when everything was ready. Those were moments of profound privilege.

First posted April 13, 2024.

I took all of the photographs you see in this post.

Note:

1. Songs from the album, Bruised Orange, by Prine still make me think of cleaning in Taliesin’s Living Room. Thanks Craig!

2. not his real nickname

3. Other staff trips not related to House Opening/Class Trips were:

- A.D. German Warehouse (Chris again)

- the Gilmore House (thanks, Juli!)

- the Lamp House in Madison (thanks, Doug!)