I know you think I know everything

at least if I listen to my mom and oldest sister

But,

this post is where I come clean about something I missed about the history of Taliesin.

it’s only one thing in the pile of things that I know I have missed

and I say that and you don’t believe me1

But I’m not being modest. I say I don’t know everything because I’ve seen it happen.

For example:

In my post “A room at Taliesin“, I wrote how when I look at drawings I try to “wipe my mind of preconceptions”, which I put a note “2” on.

What was note 2?

Regarding missing things, I wrote:

“… I remember every damned time I think about the window found in Taliesin’s guest bedroom that was staring me in the face for years in photos. I’ll write about it another time to go over it in detail. It’ll be penance.“

I don’t feel like doing penance, but it is Lent

And while I’m not a practicing Catholic, I grew up with it. Remember the ashes on my forehead in my post, “Dune, by Frank Herbert“.

So, let’s do this

For years I worked as the historian at Taliesin.

In addition to answering questions for the public and guides, I tried to figure out the history of the spaces in hopes that I could help the Preservation Crew working on the buildings.

I always felt lucky that I got to do this

When I didn’t have projects, I researched and wrote about the history of specific rooms, with the possibility of these things being of assistance when projects arose.

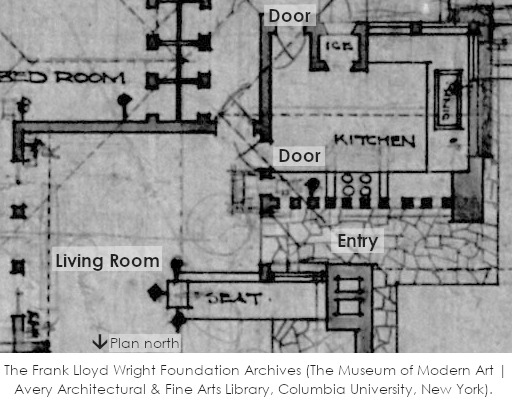

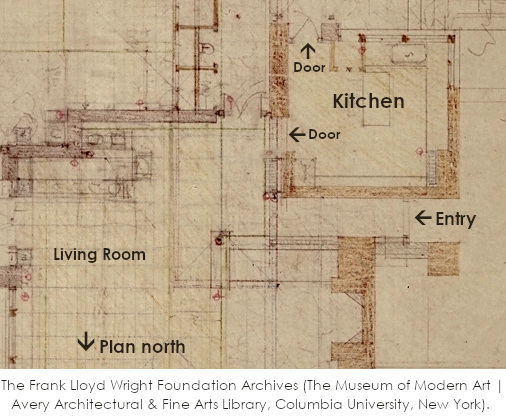

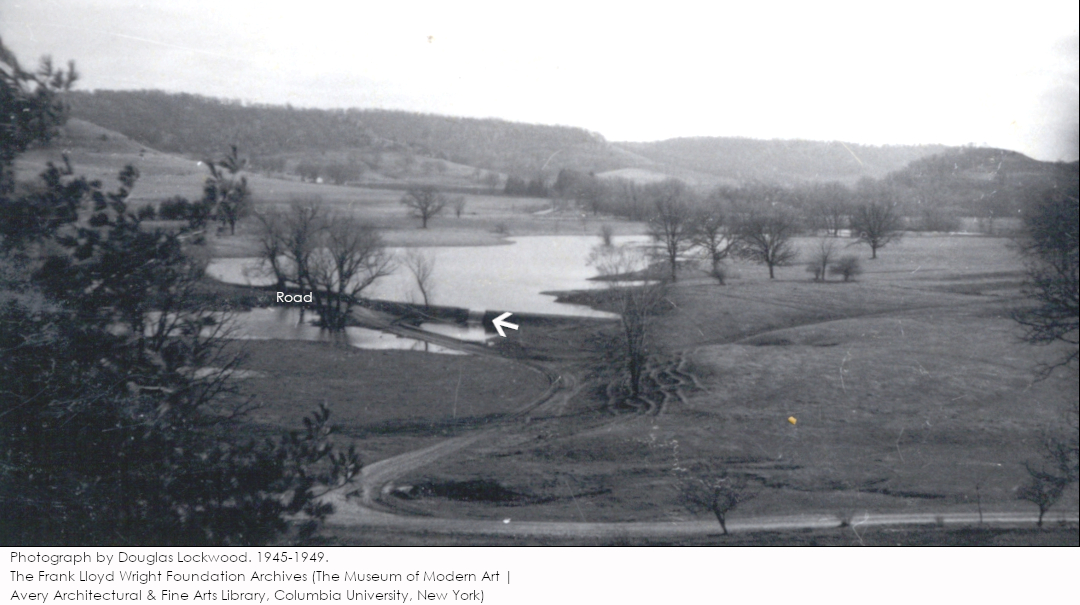

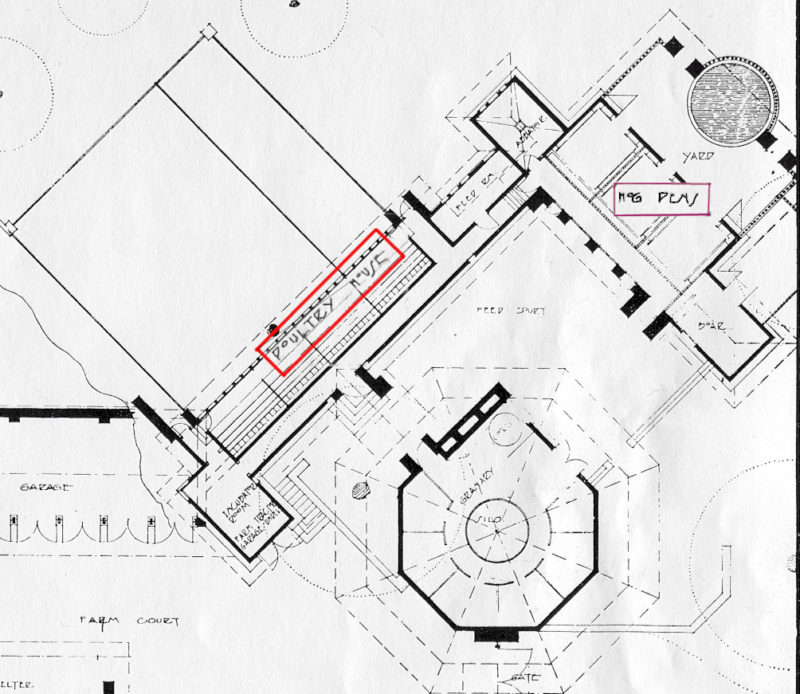

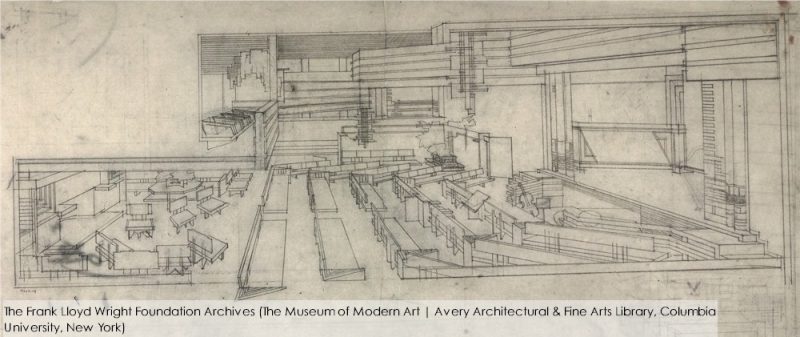

A big write-up was the “Slice” of Taliesin that I figured out.

In fact, all of this work was part of my chronologies listed for my Wright Spirit Award.

At the top of the list

Was my research about the rooms on Taliesin’s main floor.

the ones you see on Taliesin tours

One of these rooms

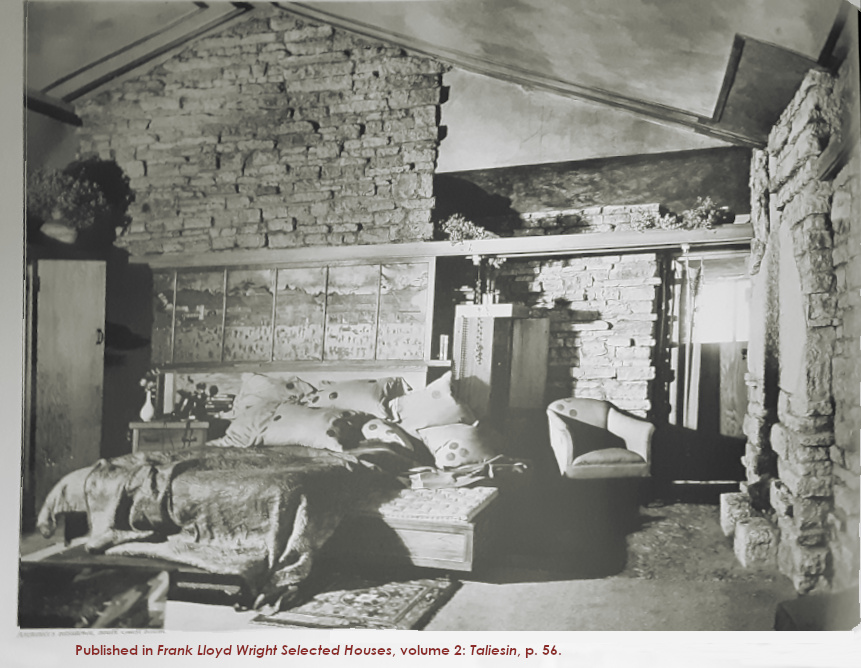

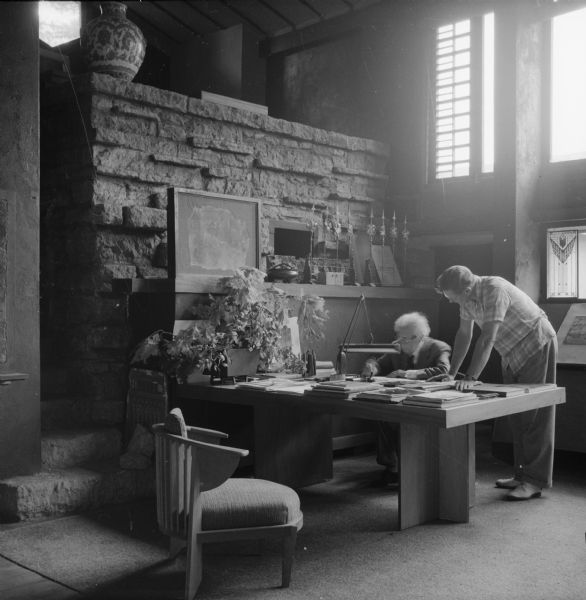

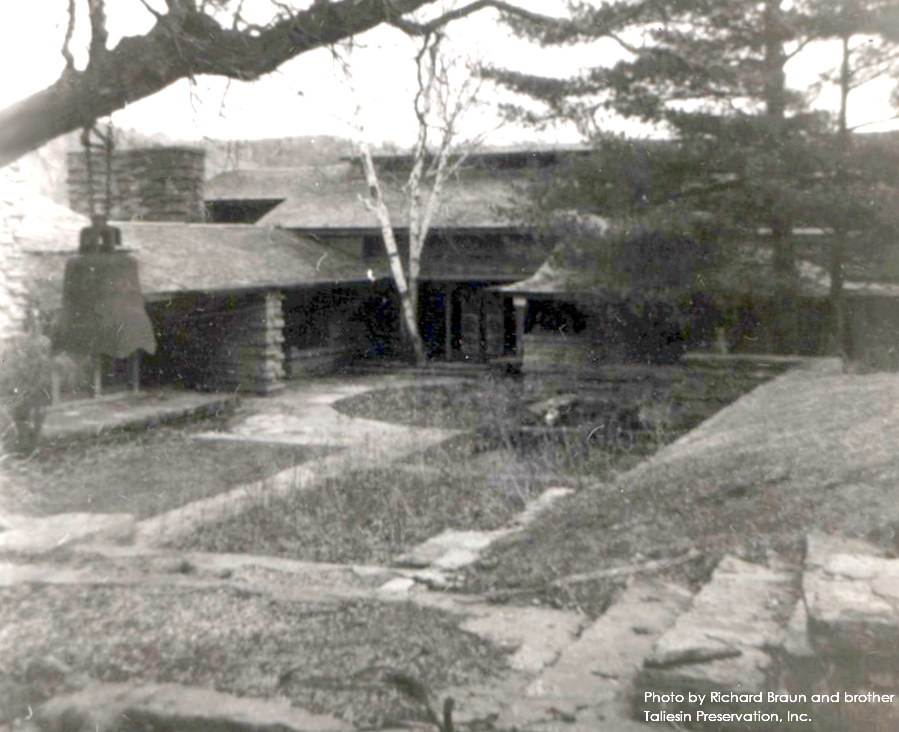

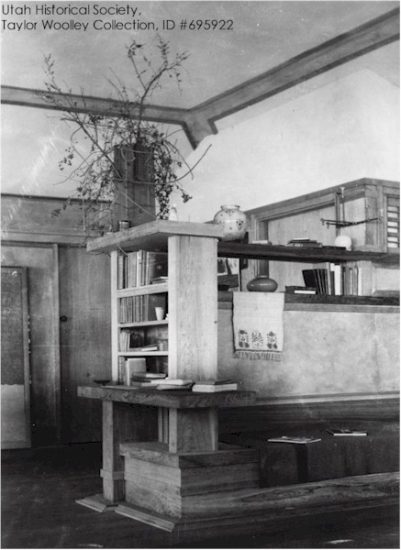

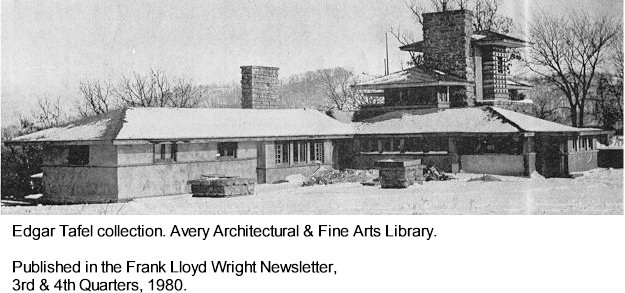

Was originally Frank Lloyd Wright’s personal bedroom. The photo of it while he and his wife slept there is at the top of this page.

The Wrights moved out of the room into their own bedrooms in 1936.2

How to we know this?

Fortunately, this information came out in an “At Taliesin” article. The article by apprentice Noverre Musson published on March 12, 1937 says in part that,

Last summer saw quite a bit of this seasonal growth….

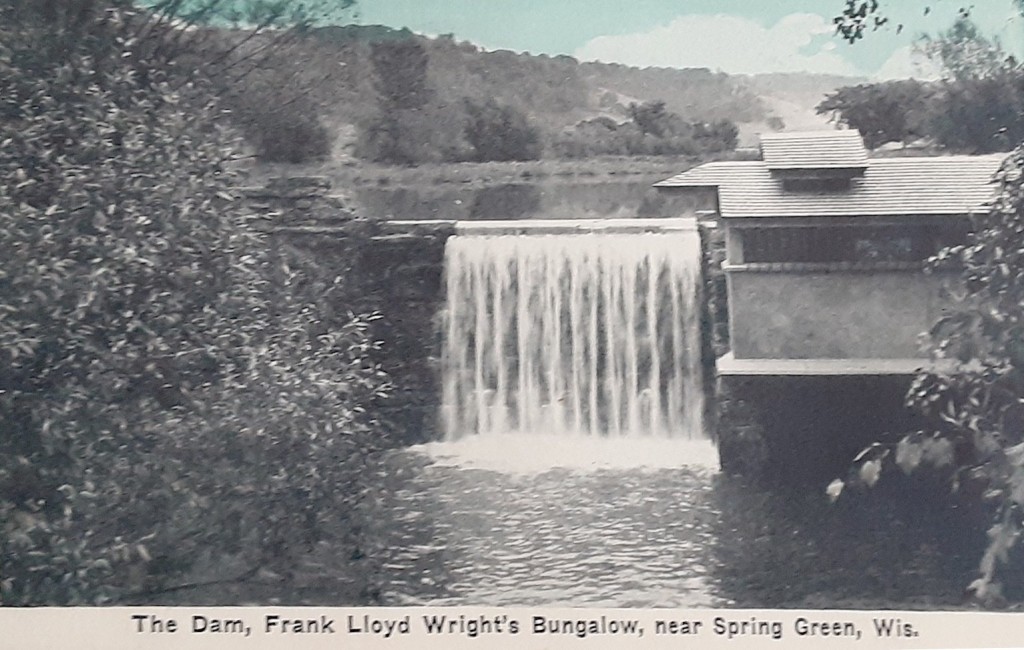

… [T]he opposite end of the house was found to be unsatisfactory in some ways. This wing which is passed first by the entrance drive had always turned its back on the approach but now sprouted a new branch to meet all arrivals. It took the form of a cantilever terrace high in the air commanding a magnificent view of the valley and provides outdoor sunny living space as complement to a sunny new bedroom, also developed from an old one, for Mr. Wright.

At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937, edited and with commentary by Randolph C. Henning (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois, 1991), p. 246.

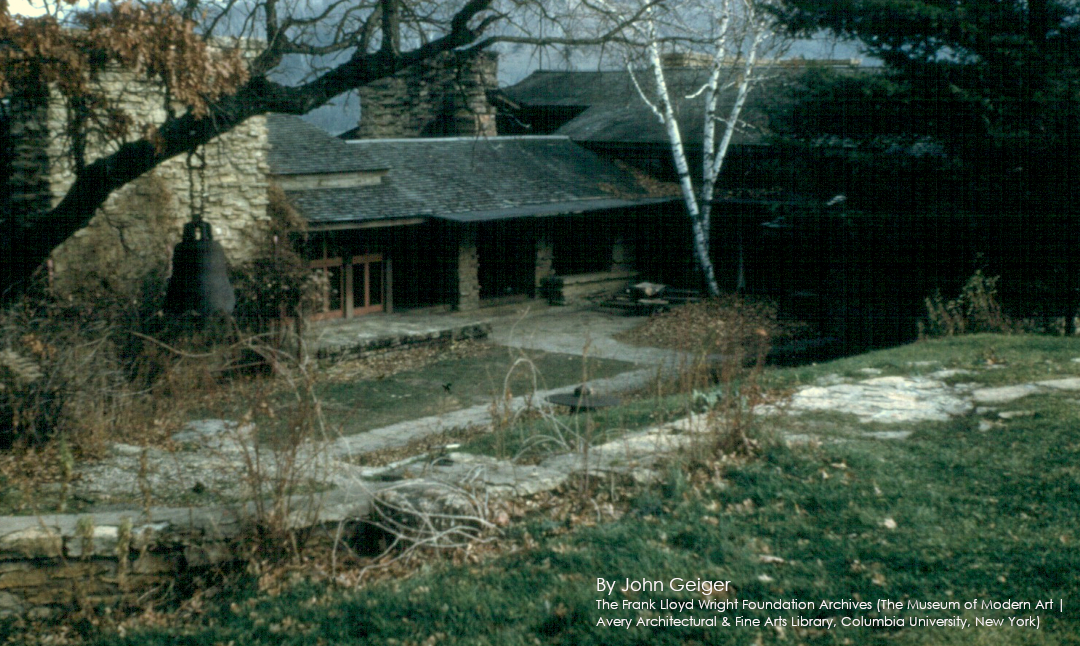

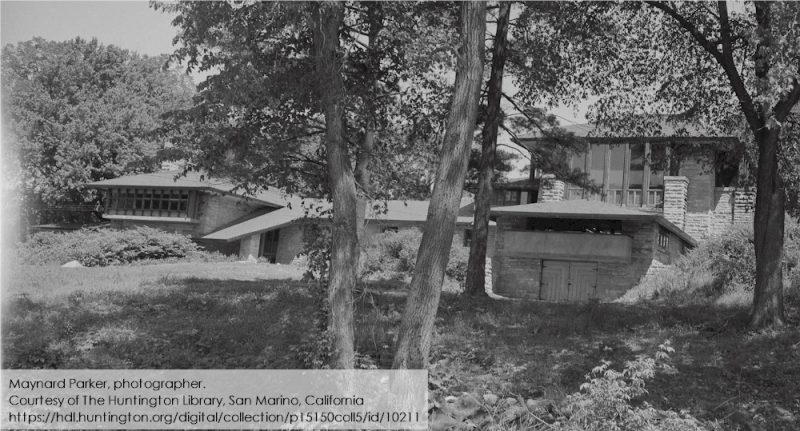

Wright built the terrace for his new bedroom (seen in this post c. 1950), which he’d formerly used as a guest bedroom. His wife took the room next to it (you can see her room down the page in this post of mine).

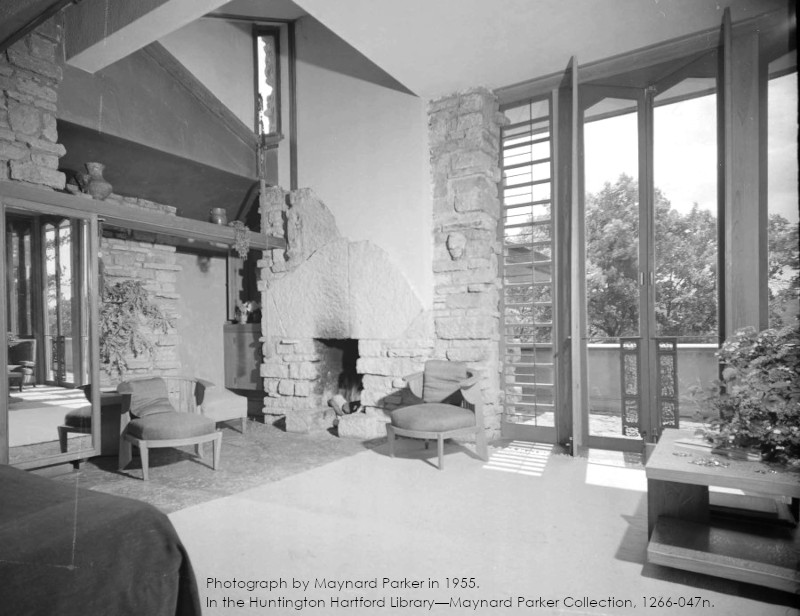

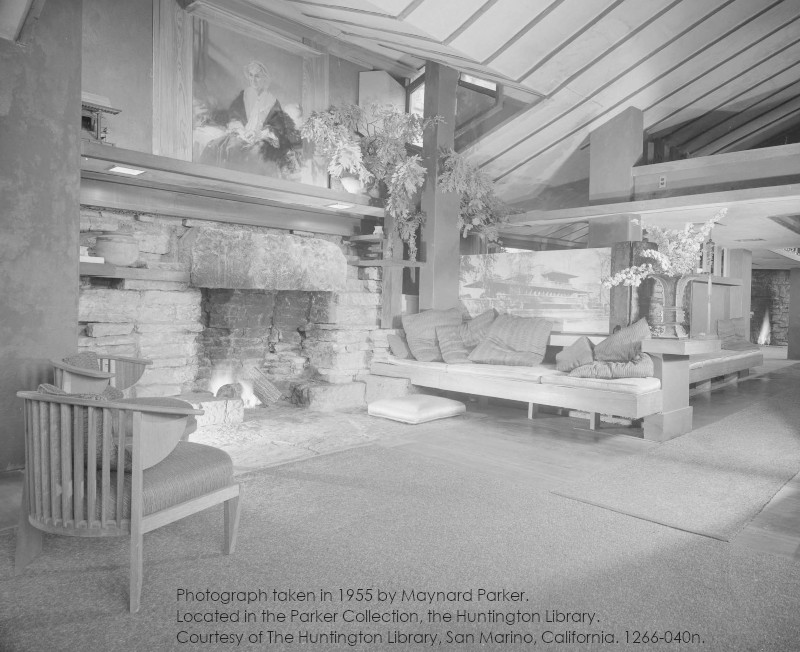

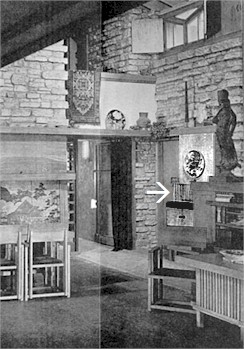

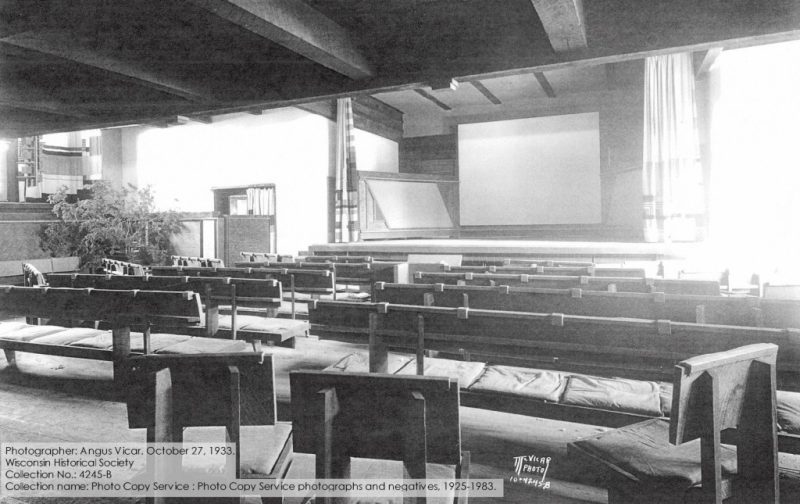

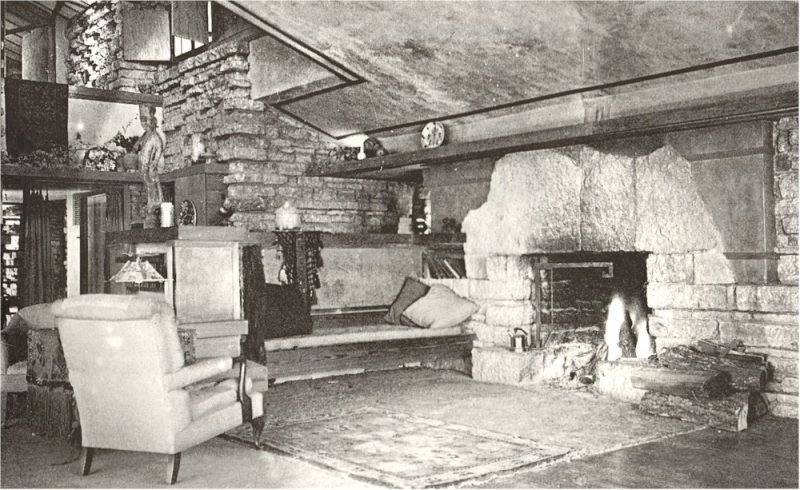

Their former bedroom remained the Guest Bedroom throughout their lives (and beyond). You can see how he changed the room when you compare the photo at the top of this post with the one below taken by Ken Hedrich in 1937:

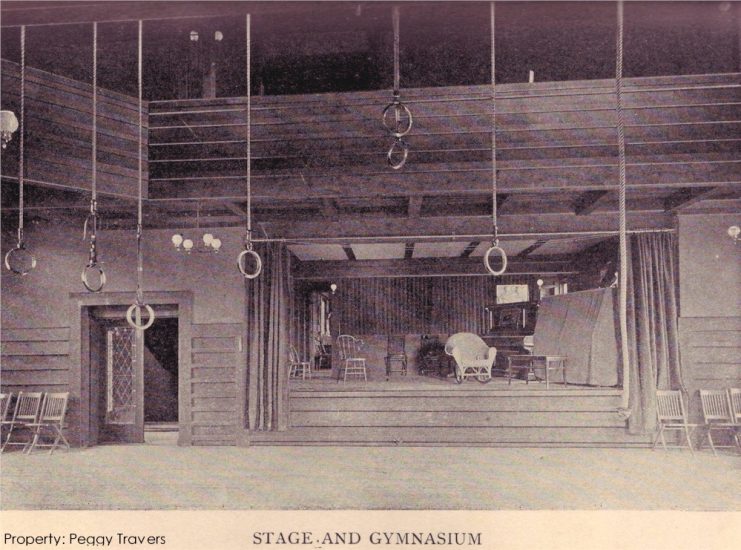

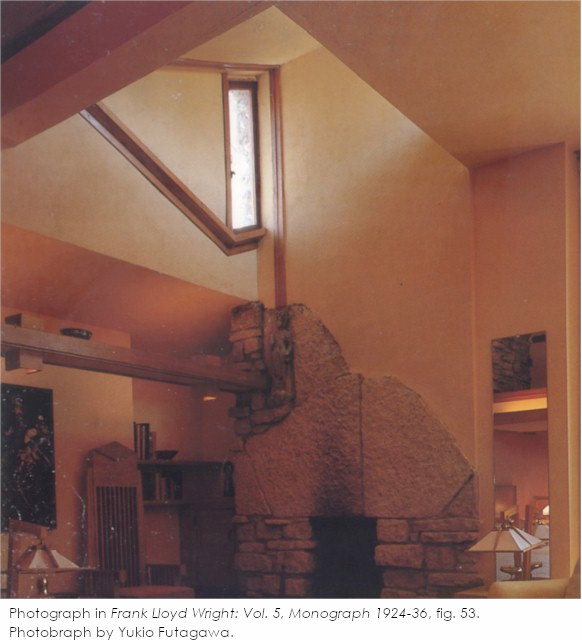

Looking northeast in Taliesin’s Guest Bedroom.3 If you walked through the door you would be in the alcove off Taliesin’s Living Room.

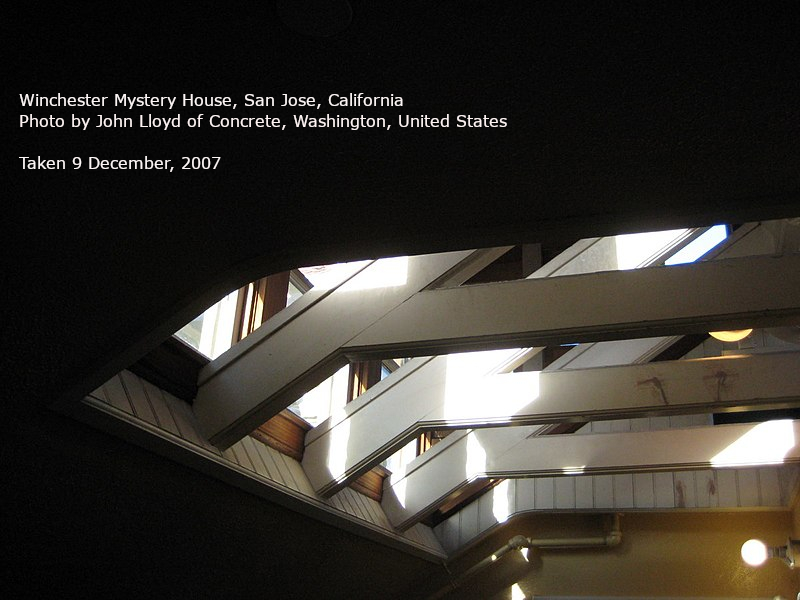

The photo also shows the underside of the room’s “loft”, like you see in this photo:

I took this photograph in 2006. I first put this photo in my post, “My March Madness“

I took this photograph in 2006. I first put this photo in my post, “My March Madness“

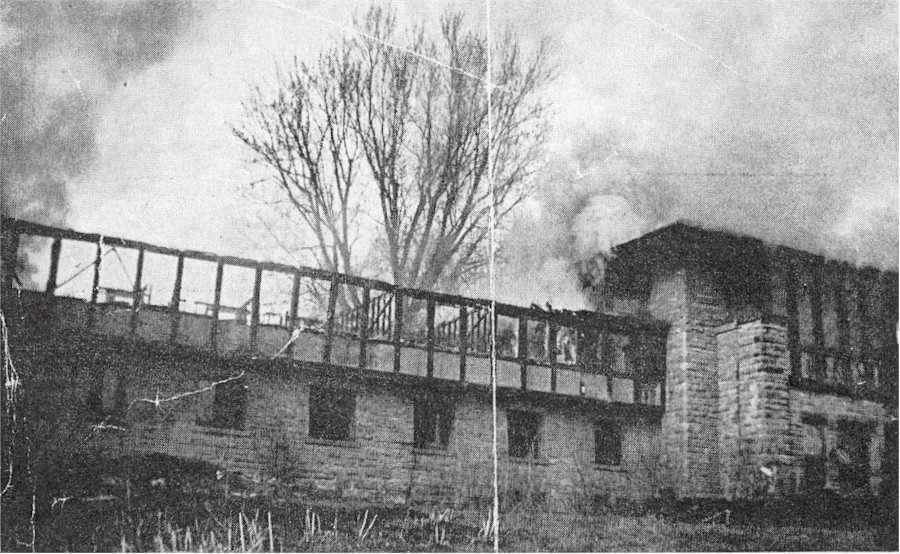

When I first started giving tours in 1994, the north side of the Guest Bedroom had drywall so I didn’t think about anything immediately around the fireplace or that north wall. In the winter of ’95-’96, the Preservation Crew worked in this room to fix a leak.

Probably due to Wright’s experimentation and changes over time, the north side of the room had (possibly still has) a leak. They work on it, then water finds its way in through another avenue and makes its way back to leaking. In fact it was leaking in this photograph taken by someone on a House tour in 2018:

But leaks are not what this post is about.

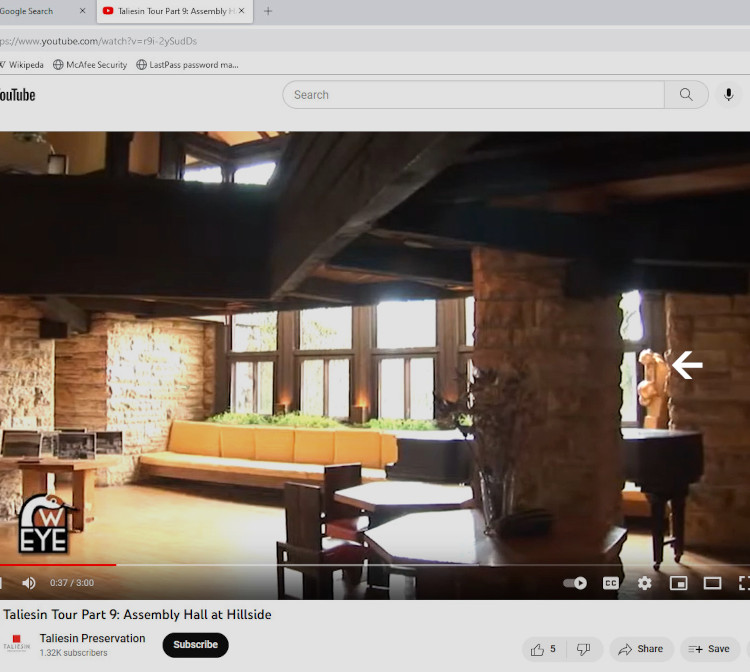

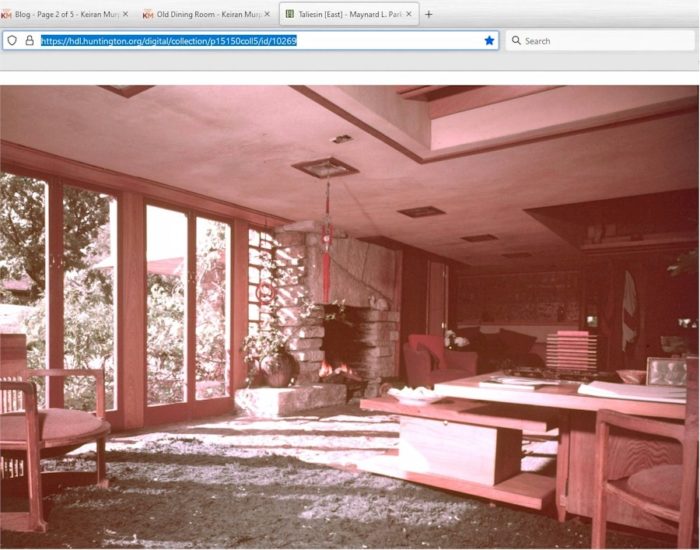

The thing I should have known (but didn’t) existed in the wall to the right of the leak. It’s a window that was found by the Preservation Crew on December 14, 2017. Taliesin’s Director of Preservation, Ryan Hewson (from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation) excitedly discusses this find on this video, here.

HERE’S THE THING:

I only knew it was there when,

thank Frank,

John Jensen, then on the Preservation Crew, uncovered it.

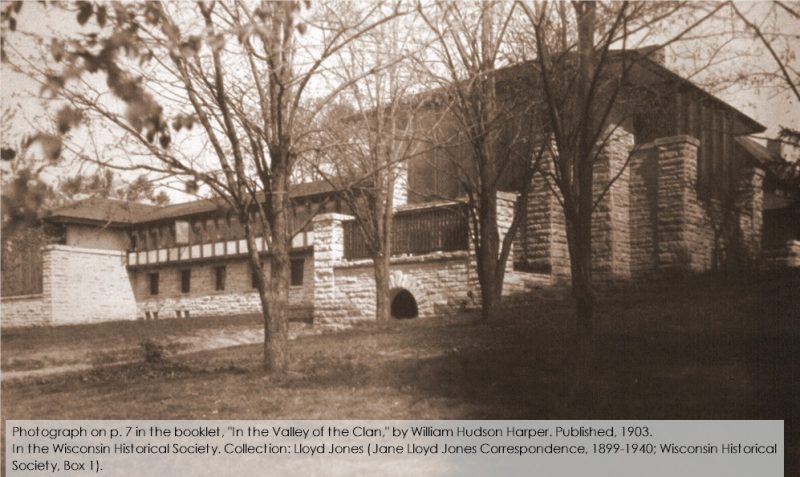

Now, to be honest, the window was covered up after Wright’s death in 1959. This is what it looked like when I first started giving tours in 1994:

After her husband’s death, Olgivanna probably wanted to make the Guest Bedroom more private. Having that open window (and French doors opening to the Loggia on the south) makes the space very light.

And it makes it difficult to sleep if there’s anyone else in the Taliesin living quarters.

Still,

I should have known. After all, I’d studied Taliesin for years and knew I had to “clean” out my preconceptions. Yet I had only seen the window in photos after John Jensen uncovered it.

And I have to say that had John not been careful he could have damaged the window and its frame.

The window you can see in Ken Hedrich’s photo from 1937 should have alerted me. But I let myself think the the light was reflecting off of something else.

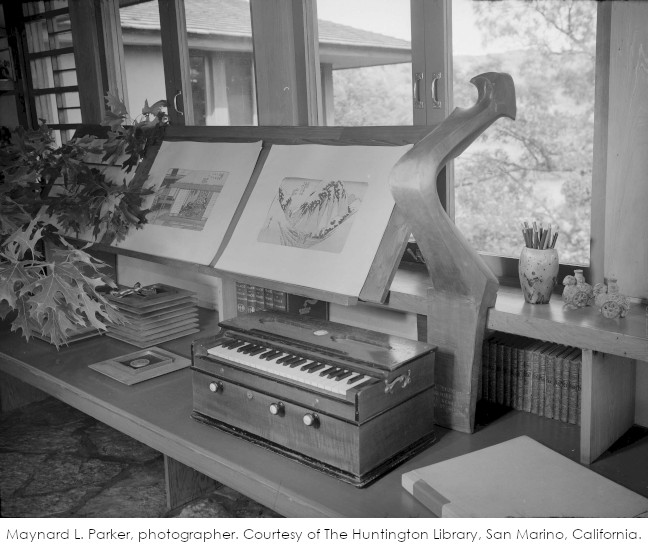

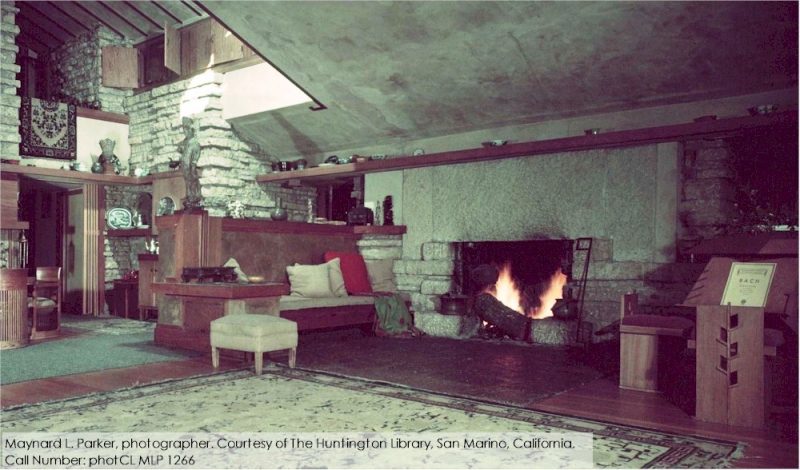

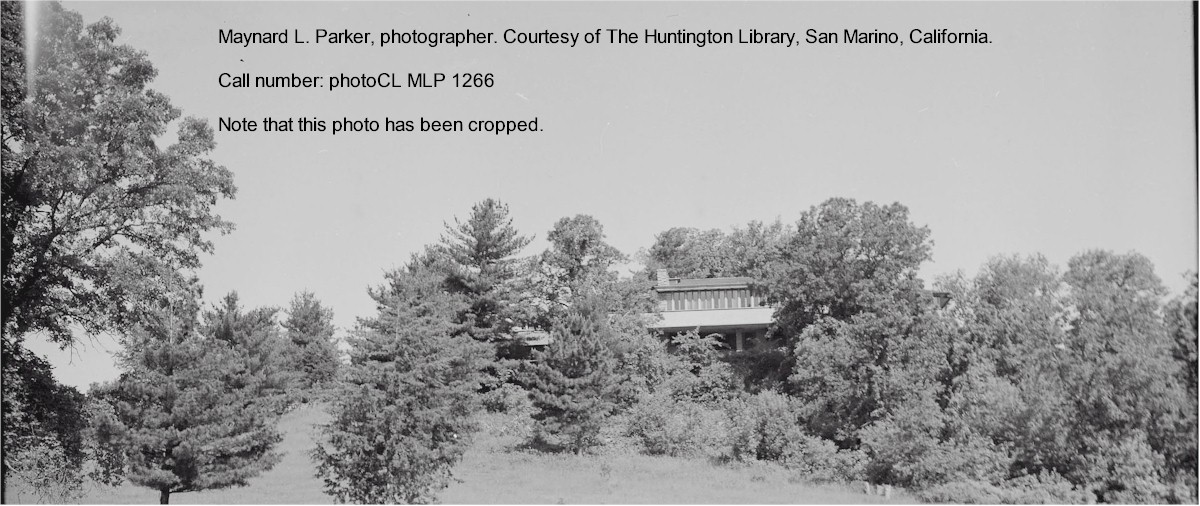

Maynard Parker took a photograph in 1955 and the lighting he used cast shadows so you can only see a window shade to the left of the fireplace:

This isn’t even the first time I’ve shown things I’ve overlooked.

Here was the post I wrote about the found window at Taliesin, and how I realized I hadn’t noticed a drawing of it for years. Of course it could also be that I mostly worked by myself.

Which led to a lot of great discoveries, but, probably, oversight.

First published March 2, 2024.

Clarence Fuermann, of the firm, Henry Fuermann ![]() Sons took the photograph at the top of this post c. 1926-28. It’s been published in a variety of places including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Selected Houses, volume 2. You can see it in the Journal of the Organic Architecture + Design Archives, here.

Sons took the photograph at the top of this post c. 1926-28. It’s been published in a variety of places including Frank Lloyd Wright’s Selected Houses, volume 2. You can see it in the Journal of the Organic Architecture + Design Archives, here.

Notes:

- Again: that’s really directed at my mom and my oldest sister.

- they got separate bedrooms probably because he slept less than she did. I’ve seen one photo of their bedroom when they shared it and the room has a drafting table in it. Makes sense, but if I were Olgivanna after awhile I’d be all right sleeping in my own bedroom after living with someone who would wake up and start drafting in the early-morning hours.

- I hear this was also called the “Big Guest Bedroom”.