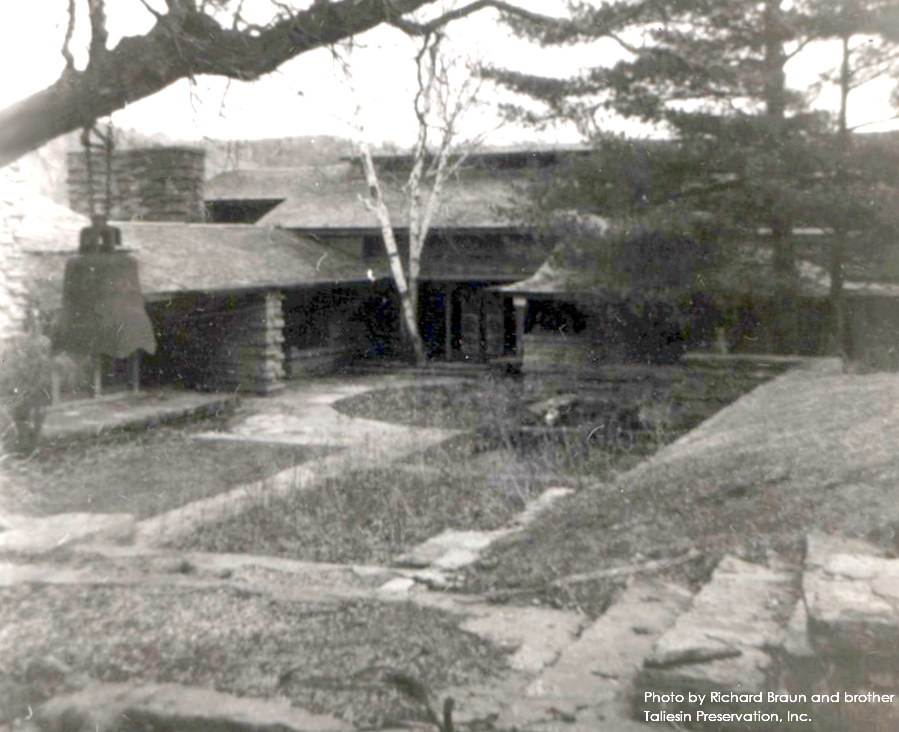

The entry to Taliesin’s Living Quarters as seen from its Hill Crown.

What’s a clerestory?

Clerestory—

“1. An upper zone of wall pierced with windows that admit light to the center of a lofty room.

2. A window so placed.”

My definition comes from Dictionary of Architecture and Construction, 4th edition (McGraw-Hill, New York, 2006)—

Yes, I own that volume. I don’t understand everything in it, but I feel super prepared.

The Art History teacher who introduced the term to me said it was pronounced “Clear-story”. But I’ve also heard it pronounced, “Cler-eh’-story”.

Yet, I only found the first pronunciation (the way I was taught). So, a big “whew” toward our teacher, Dulcia, and my own memory.

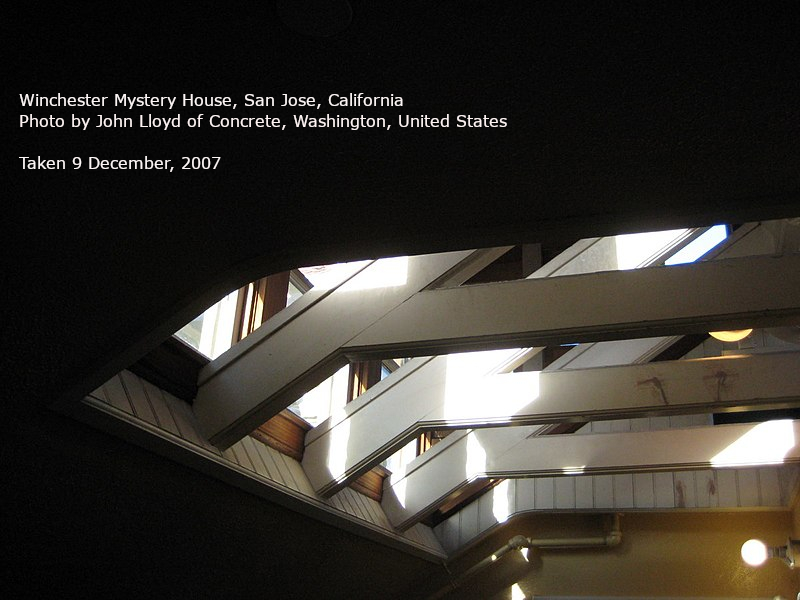

Or, easily, we’ll just look at a pretty picture from Wikimedia, of what a clerestory looks like from inside a building:

Where you see Taliesin’s false clerestory:

That’s in the photo at the top of this post, under the tallest roof you see.

You’ve also seen current photos of it in several of my posts already.

What – you didn’t realize I would constantly pull out my posts like baseball cards? Then my sneaky job of edumification is going along nicely.

Well, either that, or you’ve left the page b/c I write too f*****g much.

Oh, and that is one area where Wright, imho, changed things in ways I’m not crazy about.

You see the clerestory on tour

when you enter the living quarters.

As I wrote in the post, “Why did you have to do that Mr. Wright?”, that clerestory didn’t come in until the 1950s.

To see an early appearance in photographs, we’ll play a game of “spot the difference“.

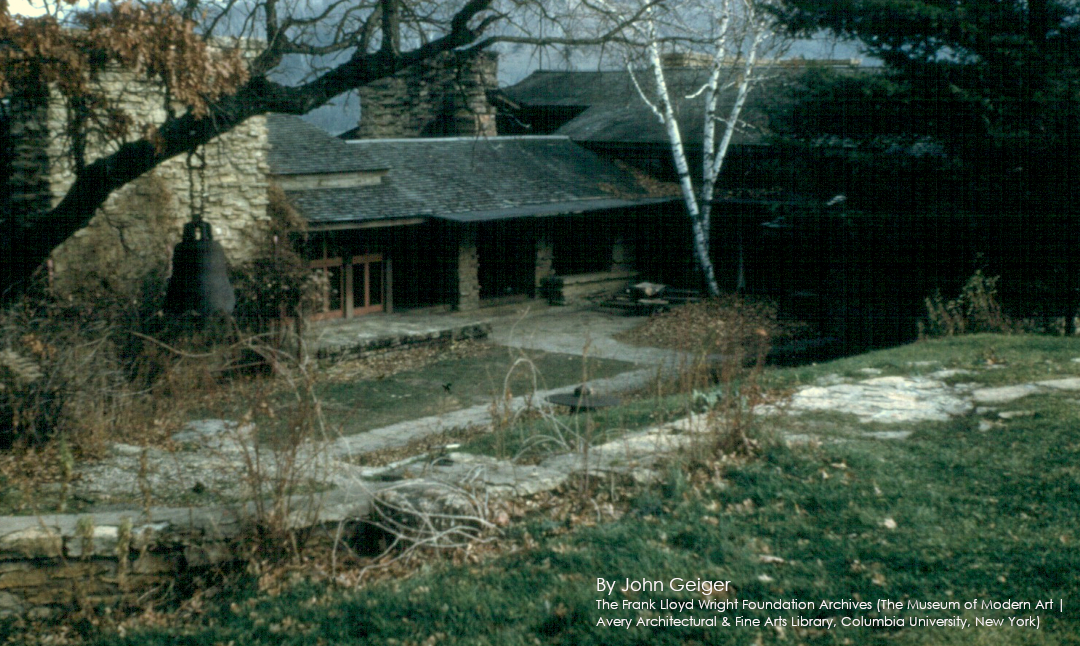

First I’ll show you the “before” photo. The photo below was taken by former Wright apprentice, John Geiger (1921-2011), when he was in the Taliesin Fellowship (1947-1952).

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

Taken from the Taliesin Hill Crown. Looking in the same direction as my photo at the top of this post.

There’s no clerestory at the roof over Taliesin’s Living Quarters.

Compare that, with what’s below.

This is the “after” photo. The photographer took this on April 3, 1953. It was also taken on the Taliesin Hill Crown and the Living Quarters has the clerestory:

Property: Taliesin Preservation, Inc.

While the Taliesin Fellowship was still at Taliesin West, Richard Braun and his brother came out to Taliesin and took a bunch of photographs. Years later, he took a tour at Taliesin and decided to give his photos to Taliesin Preservation.

Here is the kooky thing about this particular clerestory

The clerestory didn’t, and doesn’t, do anything.

Clerestories are there to bring in sunlight. This clerestory does not.

When you see the clerestory from the outside it looks as if light is coming in to Taliesin’s living quarters. Like the light coming taken at the “Winchester Mystery House” that I showed above.

Take a look at the photo I took in Taliesin’s Living Room that I posted in “Bats at Taliesin“:

If the clerestory were doing its job, you’d see a line of light in the balcony behind the Buddha that stands back there. Yet, there’s only blackness.

And the photo I took below shows what you’d see if you were standing in that balcony:

I took this photograph in February 2004.

Scanning my memory, I was probably there while working on a chronology of this part of the building. That was a crazy assignment I should write about some time.

So, why did Wright do this?

There isn’t any evidence that Wright added the clerestory for a photograph, like he did maybe for Architectural Forum (like I talked about in my last post, “Taliesin West Inspiration“).

And, while I went looking for things in my copy of Frank Lloyd Wright: Complete Works, volume 3, 1943-1959 it wasn’t helpful. Because I thought maybe he was thinking about clerestories at entrances.

But then I thought:

in order for someone to get to “the front door” at Taliesin, they’ve got to walk quite a long way.

But, I found one building that might have been part of the process. It came at around the right time. That’s –

The Harold Price, Jr residence:

a.k.a., “Hillside”. The link I put above takes you to one of Maynard Parker’s photos of Hillside, but I put a color photo of this area, below. It comes from Frank Lloyd Wright: Completed Buildings, v. 3, 340.1

I took this photo in the book with my smartphone; that’s why the photo almost looks like a painting.

There’s not a clerestory above the entrance, but a balcony. However, the view looks similar to what Wright did at Taliesin. So, when you come to the Price Jr. house, there’s what looks like a clerestory right above the door. Maybe Wright made the change because he was testing out the composition?

I mean, there were things he apparently did at Taliesin to test things out, or maybe because he liked what he did for someone else. And, like I wrote in my last post, he changed things for a photograph. But, despite how practical these things were, people at Taliesin could usually more-or-less use them when he was done.

But there’s no mistake: this design change that Wright made at Taliesin is completely unusable. Hey – it’s Taliesin Trompe l’oeil!2

First published July 4, 2022.

I took this on Taliesin’s Hill Crown in September 2008 during a garden party held for locals.

Note:

- Yes, I own all of the volumes from the “Completed Buildings” series (there are 3). I had stopped smoking, and was rewarding myself. Plus, I was hoping the books would become as valuable as the Frank Lloyd Wright Monograph series (c. $8k for the full set of the monographs in hardcover – girl’s gotta dream, right?).

- Maybe not, really. But I like those words. And Wright playing tricks with Taliesin always pleases me.