Yah: what about Wright’s second wife? That’s who I’ll write about today.

Years ago, a group of coworkers and I performed a comedy sketch for a friend who was leaving Taliesin Preservation. At one point in the sketch, we voiced common questions that folks ask when they take a tour. Among them were “how tall was he?” and “why are all the ceilings so low?”

[which is simply hi-larious lemme tell you]

But my favorite made-up question was from the co-worker who said the title of today’s blog post. I found it such a brilliant, off-hand “joke for the world’s smallest audience”.

But that begs the question: what about Frank Lloyd Wright’s second wife?

Those in the Wrightworld know

She wasn’t Mamah

Wright and Borthwick never married.

That was in part because Wright’s first wife wouldn’t grant him a divorce. I think that Wright would have married Mamah, despite the fact that he spoke a lot at that time about changing roles of marriage and women, due to their reading of Swedish feminist, Ellen Key. Key promoted the concept that women should not be the property of their husbands.

Yet, he understood at that time that he needed to place Mamah “under my protection” (as he said) at Taliesin.

The woman of the couple “living in sin”

would be in a terrible position to earn a living. The Dodgeville Chronicle newspaper reported in its January 5, 1912 article that Wright told them:

“The only circumstance which is the basis for the statement that I eloped with another man’s wife or deserted a wife or abandoned my children will be found in the fact that I neglected to inform the newspapers of Chicago of my intentions and the arrangements which had been made honestly with all who had any right to be consulted.”

No: Wright’s second wife was Maude “Miriam” Noel.

While I touched on her once before, I will be writing about her in this post. That’s because her birthday is May 9 (she was born in 1869).1

She was born Miriam Hicks in a suburb of Memphis, Tennessee, and took the last name of Noel after her marriage to Emil Noel. They might have married when Miriam was 15.2 The two of them moved to Chicago, where Miriam had their three children. Miriam and Emil later divorced.3

She went to Paris in the first decade of the 20th century,4 and became a sculptress (although nothing of her work survives). Apparently, she left Europe at the start of World War I to return to Chicago and live with her daughter, Norma.5 Now, WWI starts in full force by early August, 1914, and the fire and murders at Taliesin happened on August 15. Noel read about the murders, which recapped Wright’s personal scandals (etc. etc., plus ça change).

The papers, then, were inundated with the stories of the lives lost at Taliesin.

While Wright wrote years later in his autobiography that he destroyed piles of sympathy letters, he did read some of those sent to him. That’s because, while he was receiving too many sympathy letters to count, there were still business correspondence that he had to attend to.

So, Wright instructed his draftsmen in Chicago to go through the letters and contact him with anything of importance. Apparently, one of the men thought he would be cheered by this letter of sympathy that said that, as an artist who had suffered loss, she understood where he was. Wright received the letter in December, 1914.

The architect acknowledged it, so Noel wrote another one. According to biographer, Finis Farr, in the second letter, Noel suggested they meet:

[A] few days later Miriam Noel sat opposite Wright’s desk…. He saw a woman who was no ordinary person, and who retained much of what had evidently been great youthful beauty. Richly dressed, with a sealskin cape, she had a pale complexion contrasting with her heavy dark red hair….

“How do you like me?” Miriam Noel asked.

“I’ve never seen anyone remotely resembling you,” said Wright.6

Wright was in a very delicate spot.

Years later, regarding his mourning for Mamah, he wrote that,

A horrible loneliness began to clutch me, but I longed for no one I ever loved or that I had ever known. My mother was deeply hurt by my refusal to have her with me. My children—I had welcomed them always—but I did not want them now. They had been so faithfully kind in my extremity. I shall never forget.

But strange faces were best and I walked among them.

I do not understand this any better now than I did then. But so it was. Months went by, but they might have been, and I believe they were, for me, a lifetime.7

IMO,8 Miriam, whether she planned it or not, was the perfect person for him at that point. Wright was probably among the walking dead in those months after August 15, 1914. And along came this sensuous stranger, who he probably engaged with physically very early. The emotions, and intensity, probably distracted him emotionally.

In fact, very quickly the two were plunged into drama. By August of 1915, she wrote him these letters that implied already that they were having emotional fights. If you want to see some of this, read the November 28, 1915 edition of the Washington Herald newspaper (available via Chronicling America from the Library of Congress). The story includes part of one of the letters that Miriam had written in August 4. The writing is… turgid:

“I went to pieces at mention of the things that were going on at Taliesin. The disappointment was too horrible. I shall always go to pieces like this, I know. Your letter has just come. For God’s sake do not torment me by relating your life as it is at Taliesen [sic].

Fears Her Own Emotion.

“Do not come. I cannot see you again. It will simply precipitate another outburst. Your carnivals at Taliesin are not for me. I do not want to be in them nor do I want to be told of them. A merry party of debauchers using your house for purposes too shocking for words—invited for that purposes. . . . if you write me again about it, I don’t think I shall be able to read the letter.

Why are you reading these “turgid” letters?

That’s because of a woman named Nellie Breen.

Nellie Breen was Wright’s housekeeper. Wright unfortunately left her in charge of his home on several occasions. At that time Breen got a hold of letters written by Noel to Wright. Due to this, Breen went to the United States Department of Justice and filed charges against Wright. These charges were for Wright’s violation of the Mann Act.

Created in 1910, the Mann Act

“criminalizes the transportation of any woman or girl for the purpose of prostitution or debauchery, or for any other immoral purpose.”

Or: another thing I learned while working at Taliesin.

Breen said Wright was violating the Mann Act by bringing Noel into Wisconsin from Illinois. And Wright had the charges dismissed due to the work by the lawyer Clarence Darrow

– yes it’s true! Wright really was related to ever-y-thing!

Ok, coming back from that

Thanks, Clarence!

Wright would stay with Miriam, from this time, and into his work in Japan on the Imperial Hotel. I theorize that Wright’s responsibilities on his commission kept him busy enough to get along with Noel for periods of time.

Wright’s son, John, had a front row to the relationship:

I remember… when Dad soft-shoed into the drafting room and read her note to me. He thought it wonderful. I thought it terrible. Dad viewed the occasion so lightly, he smiled when the poetess faced him, he winked and the poetess chased him. He had an empty place with him and he felt a need to fill it up with something that is a little like love, or was it poetry? But, as the drama developed and the meaning of the poetry became clear to Dad, it was too late.9

The last of the relay race:

Wright finished the Imperial Hotel, and he and Miriam came back to Taliesin by August 1922. That November, his first wife, Catherine Lee Tobin Wright, granted him a divorce. Then Wright and Miriam married in November 1923.

The second Mrs. Wright left him by May of the next year (1924). The two began divorce proceedings, which were stopped when, apparently, Miriam found out about Olgivanna (who I wrote about regarding Taliesin’s 1925 fire).

Which ignited Miriam’s revenge.

That a surprise? Look at the damned letter in the Washington Herald that she apparently wrote after they’d only been together for 8 months!

And on, and on, the relationship between Wright and Miriam twisted and tangled up, losing Wright his clients and even more dignity within the American press.

Lastly

If you want to read about Miriam, there are the biographies by Meryle Secrest, Brendan Gill, and Finis Farr that I wrote in the Notes, below.

In addition, author TC Boyle made her into a hell of a character in his book,

or an annoying PITA, depending on your viewpoint; both of which are legitimate

The Women (Penguin Books, New York, 2009).

One of our staff members read it to us at lunch. I wrote about this when I related some of what we did at my old job during the Winter.

First published, May 2, 2023.

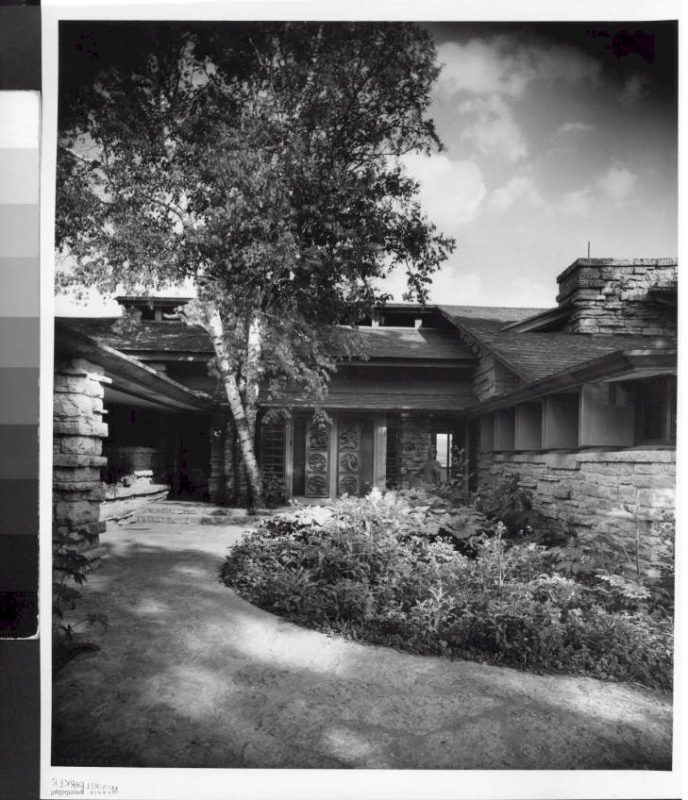

The image at the top of this post comes from the cover of the November 28, 1915 Feature Section in the Washington Herald newspaper.

Notes

1. Miriam Noel died on January 3, 1930.

2. Meryl Secrest Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, New York City, 1992), 238.

3. Brendan Gill. Many Masks: A Life of Frank Lloyd Wright (G P Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1987), 235.

4. Secrest, note on page 581. According to Secrest, Emil Noel died in 1911. Secrest didn’t write whether Emil and Miriam were living together at the time, or if Miriam had left for Paris without her husband in 1904.

5. Meryl Secrest. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography (Alfred A. Knopf, New York City, 1992), 237-238. I’ve taken the basic biography of Miriam Noel from Meryle Secrest’s biography. Noel appears in the chapter, “Lord of Her Waking Dreams.” That title is a modification of what Noel wrote to Wright in a letter.

6. Finis Farr. Frank Lloyd Wright: A Biography (Charles Scriber’s Sons, New York, 1961), 146, 147. Farr wrote that David Robinson, the Office Manager, gave him the letter. Ok: so that’s the guy we can blame for Wright meeting Miriam.

7. Frank Lloyd Wright. An Autobiography (Longmans, Green and Company, London, New York, Toronto, 1932), 191.

8. and, if I haven’t said this before: the tenor of this post is pretty much all imo. Not that I’m wrong, I just don’t want you to think that this is the lasting authority.

9. John Lloyd Wright, My Father, Frank Lloyd Wright (originally published as My Father Who is on Earth (G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1946; Dover Publications, Inc., New York; 1992), 108-109.