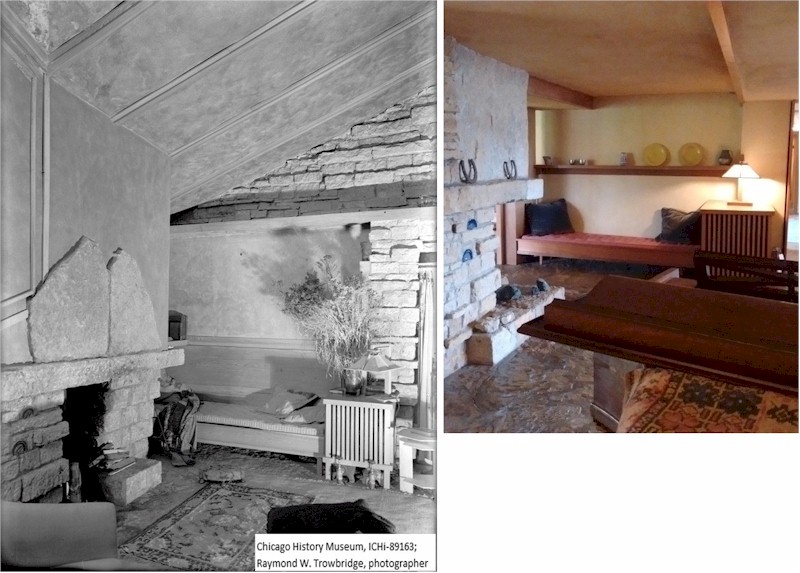

Two views of the same space, 89 years apart.

Frank Lloyd Wright began his home, Taliesin (south of Spring Green, Wisconsin), in 1911 and worked on it almost continuously until he died in 1959. As researcher and historian I easily documented over 100 changes he made just to his home (that number doesn’t include the necessary construction after Taliesin’s first or second fires).

And this doesn’t count his work on the other buildings on the Taliesin estate; about which you can read at Wikipedia. If you go to the Taliesin (studio) page, there are links to the four other buildings on the estate. Yes, I did start all of the Wikipedia entries on those Taliesin estate buildings, why do you ask?

And the changes I numbered were just those that could be documented through photographs.

Taliesin is very important, yes

That’s why we call Taliesin a sketchbook. In addition, it was an experiment for the artist/architect/genius-extraordinaire [that looks like I’m being snotty, but I’m not].

I was told by someone who worked in the Wisconsin State Historic Preservation Office that when they began talking about Taliesin restoration, they didn’t want to create the Taliesin “zoo”. As they restored/preserved the building, they didn’t want to pick out what they thought were the “best” changes done there by Wright.

Their conclusion: restore Taliesin back to the last decade of the architect’s life, 1950-59. And as close to 1959 as possible/doable, combined with new technologies that wouldn’t screw up the building in the future. So that’s how, for example, Taliesin got geothermal heating and cooling.

And I agree. I fiercely want Taliesin to be as it was in Wright’s lifetime—as long as the “building envelope” is “sealed” to help the building survive long past my death.

YET

I wrote all of this because I have a confession: there are changes I really wish that guy hadn’t made to his home.

Some things that used to be at Taliesin just seem so cool. Their rarity is part of the attraction. And, yes, I love what is there today… but sometimes I really wish he’d left well enough alone.

Look below for an example.

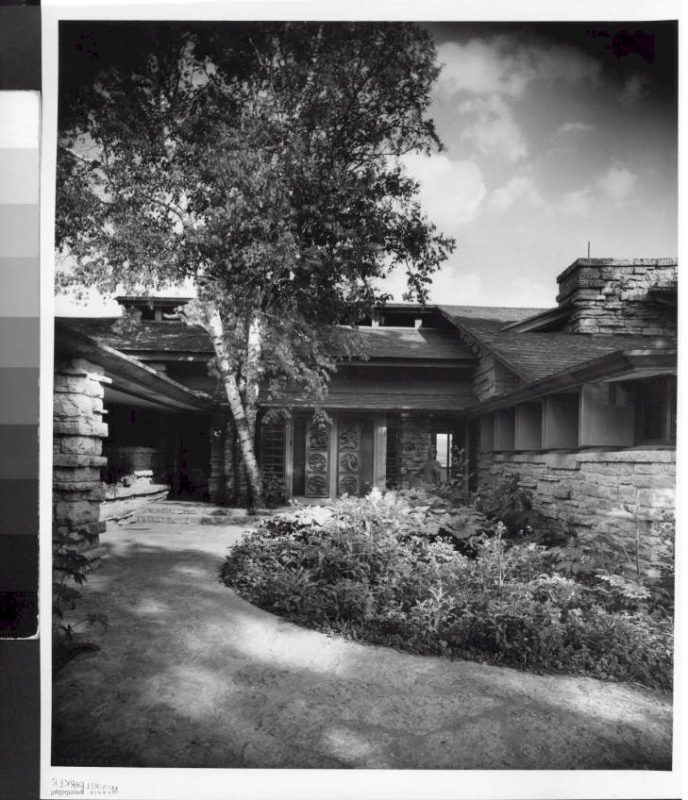

The first photo, taken 1926-33, shows the entry to his living quarters. The part you see under the roof is what I’m talking about. Between those three stone piers were French doors. They opened to the exterior balcony that ended at a parapet behind where that teenage boy is sitting (he’s sitting on a little bit of roofing). He added the balcony in Taliesin III (so, after the second fire). It stood one floor above today’s “front door” at Taliesin.

Then in 1942 (approximately), Wright constructed a roof over that balcony, making it into a storage room. Former Wright apprentice / longtime Taliesin Fellowship member John DeKoven Hill called the room “the hell hole”.

The same view in the 1950s:

The next photograph shows the same part of the building, with a roof where the balcony used to be. It’s the configuration one sees today:

Maynard Parker took the photograph above in 1955 by for House Beautiful magazine. Then you click on the photo above, at the website of its owners (the Huntington Library) it’s backwards from its correct orientation.

What you see in the 1955 photo by Parker/for House Beautiful, is great, of course. But I look at archival photos, or scan what’s in my memory, comparing it to what he had before 1942 and I want to whine: “oh man – why did you do that?”

Then, here’s what I’m thinking: “grumble, grumble – sketchbook — grumble grumble… architectural genius… grumble grumble… HIS gorram house… grumble…”

But what right do I have, given the mistakes from the past?

… you can’t deny all those times in which people, with the best of intentions, completely destroyed something.

Like so many buildings by architect Louis Sullivan in Chicago

And Wright’s Larkin Building in Buffalo

Check out this from the Buffalo City Gazette shows newspaper articles talking about the building’s decline

You get the point.

FINALLY

There’s also the fact that the National Park Service, which confers “National Historic Landmark” status, is firmly against people “creating a false sense of history.” That is a hard-and-fast rule.

Besides, if Taliesin had all the things in it that I really like it would end up being a Taliesin that never actually existed.

But I can still yell at him in my head, though.

Initially published on May 4, 2021

At the top of this page are two photos. The one on the left was taken in 1930 by Raymond Trowbridge (who I’ve written about) and is at the Chicago History Museum (and online here). I took the photo on the right a couple of years ago, showing the same room. You can tell it’s the same because what remains the same in the two photographs are the ceramics in the fireplace on the left and, against the wall, the built-in bench and the radiator cover. He lowered the ceiling in 1933-34 when a bedroom/sitting room was built one floor above for his youngest daughter, Iovanna Lloyd Wright.

1 accompanied by lots of words for him that I cannot repeat in polite company.