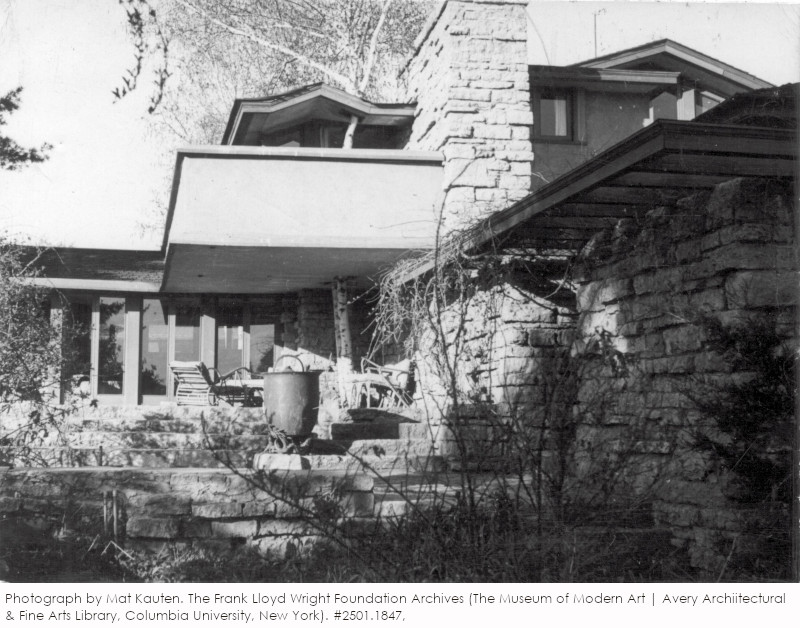

Photographer (and apprentice) Mat Kauten took this photograph looking at Taliesin’s Garden Room in 1944. I think Gertrude Kerbis might have seen Taliesin at the same time of year that Kauten took his photographs.

Here’s the story: a while ago, I received an email from Elizabeth Blasius, an architectural historian and co-founder of Preservation Futures.1

Blasius had questions about a memory that award-winning architect Gertrude Kerbis spoke about on a couple of occasions. Kerbis talked about some obscure things relating to Taliesin, so Blasius had asked people she knew who might know the answer. So, of course she went to someone in the Wrightworld.

she’s in Chicago, a place filled with Frankophiles.

Eric Rogers, Events and Communications Manager at the Frank Lloyd Wright Building Conservancy, gave her my name and contact info.

Her questions, and my answer, are what this post is about.

In part because they let me do one of my favorite things: walk around Taliesin in the past.

Kerbis was not an apprentice in the Taliesin Fellowship and apparently never met Frank Lloyd Wright.

But

circa 1945, she had an encounter with Taliesin that changed her life.

Blasius wrote and told me that while Kerbis was a student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, she:

[R]ead a Life magazine article about Frank Lloyd Wright. She was fascinated with his work, and discovered that Taliesin was not far from Madison.

She then hitchhiked to Spring Green, and found herself on the grounds of Taliesin.

FYI: Spring Green is around 45 miles (72 km) west of Madison.

When Kerbis arrived at Taliesin, no one was there. Still, she walked all around it, and looked in through its windows.

At one point

she heard steps behind her, turned around and there was a white peacock in “full flutter”.

Sounds like the peacock was standing its ground; I doubt it thought she was a mate.

After the peacock incident

Kerbis realized it was late. Since she’d hitchhiked all the way out there, she decided to hunker down and stay at Taliesin.

She said that, luckily, she found an open window into a bathroom and climbed in! Then she spent the night in one of the bedrooms. While she never mentioned what her bedroom was like, she found a record player and played Beethoven.

Blasius told me that “next morning she had decided to become an architect.”

Blasius was of course curious about this. I would be, too:

- How the hell could she walk around all over the place and not see anyone? She stayed overnight, so it’s not like the Wrights had just gone out for dinner.

- And were there really peacocks at Taliesin?

Her email made my day.

It was a puzzle with all these pieces that I knew.

So, yes: what Blasius relayed to me made total sense.

First off:

Kerbis didn’t see anyone at Taliesin that day because, after the late 1930s, Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship picked up and left Wisconsin every fall. Therefore, the Wrights and the community of men and women working and living with them migrated to Taliesin West in Arizona. They would settle at T-West, and continue living in their community and working on Wright’s architectural commissions until the following spring.

Secondly:

Kerbis, while walking around Taliesin, saw “floor-to-ceiling” windows at Taliesin according to Blasius.

This also made sense to me.

Since Wright no longer lived in Wisconsin during the winter, he opened up the rooms and put glass into more walls

like I wrote about here and here.

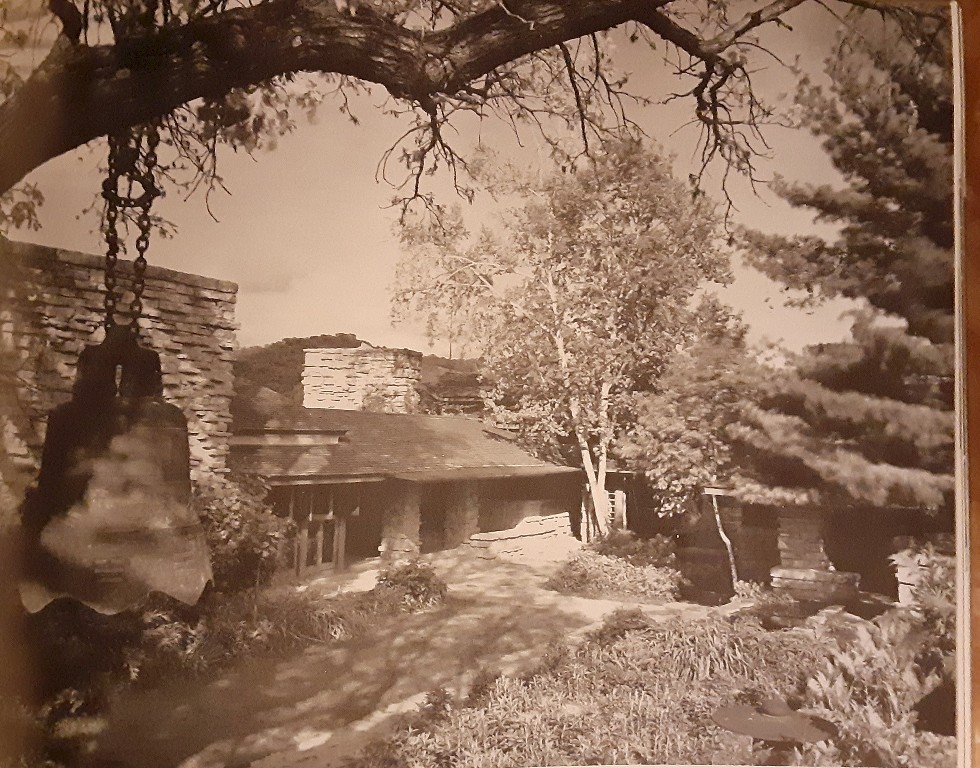

I pictured where Kerbis would have walked around and seen through those windows, like into the room at the top of this post. And in the photo below by famous photographer Ezra Stoller:

Photograph in the book, Masters of Modern Architecture, by John Peter (Bonanza Books, New York, 1958), 47. I showed this photo in my post, “In Return for the Use of the Tractor“.

There’s a black rectangle to the right of the birch trees that’s really a floor-to-ceiling picture window. And the French doors on the left look into the Taliesin Drafting Studio.

As for peacocks:

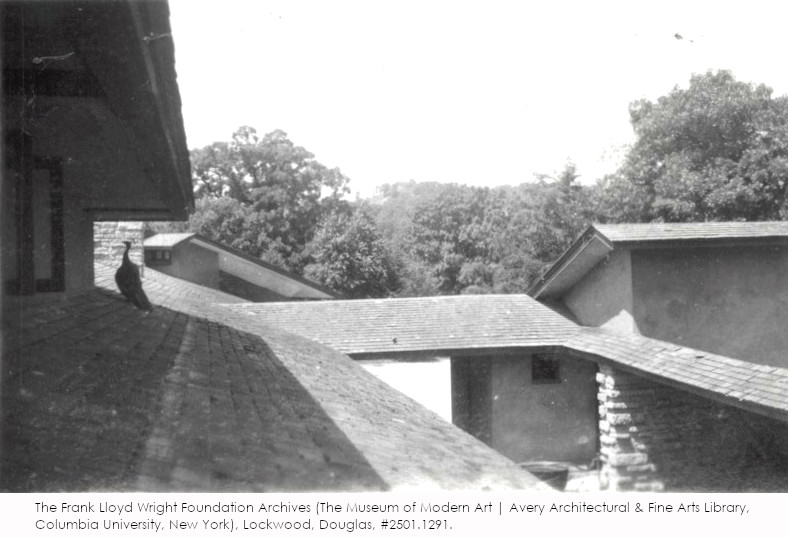

I knew that some lived at Taliesin. I never heard they were white, but I’ve seen at least one photo of one. And that’s below:

Taliesin apprentice Douglas Lockwood took this photo at Taliesin sometime after World War II. The peacock is on the left under the roof outside the Hill Wing apartments.

Was Taliesin totally abandoned every year?

No. While most of the Fellowship went to Arizona, some apprentices stayed in Wisconsin for the winter. They took care of the animals and watched over all the buildings. Their work paid their tuition.

If there were people, why didn’t Gertrude see anybody?

Members of the Fellowship didn’t live at the Taliesin residence in the winter. They inhabited Midway Barn. It’s on the Taliesin estate and is less than half a mile away from Taliesin. But you can’t see Taliesin from Midway.

Kerbis and the bathroom:

Is that true?

Yes, it is. If you were a thin enough.

There’s one place in the building where you could see a bathroom from the outside, with a window that’s large enough to crawl through (for a petite person). There’s another bathroom you could see a little bit, although I don’t think you could crawl into it through the window. But both of them are on the ground floor of Taliesin.

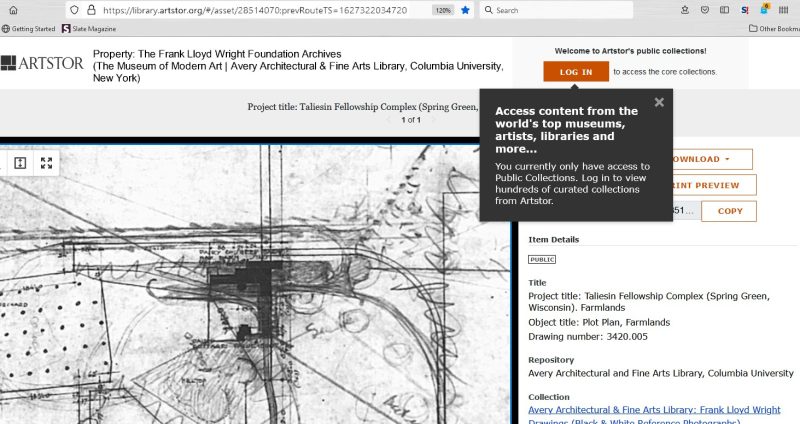

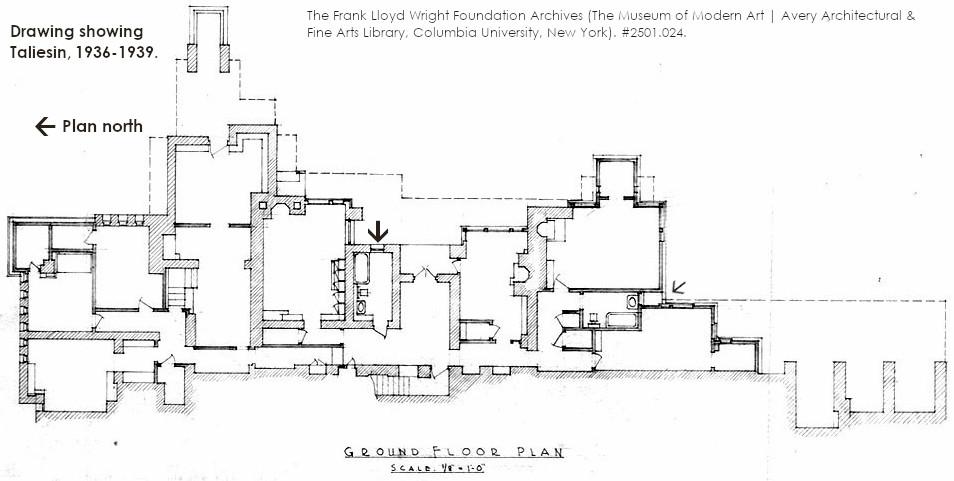

I couldn’t find good photos of either bathroom area. But a good plan of that floor is at ARTSTOR. I’ll show a version of the drawing below with arrows pointing out the bathrooms:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). Drawing #2501.024.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). Drawing #2501.024.

This drawing was executed 1936-39. Wright changed a few things on this floor by the time Kerbis came to Taliesin in 1945. But the two bathrooms were and are still where the arrows are pointing. The bathroom on the right has a really, really, small window, so I don’t know if that would have been open when Kerbis was walking around.

While there are two bathrooms, I think only a diminutive person could crawl through into the bathroom on the left.

BY THE WAY you scoundrels: in my 25 years, I never saw those windows open at Taliesin so don’t get any ideas.

The next day when she woke up

Gertrude decided she was going to be an architect.

She tells the story in this video about her.

She starts talking about her experience at Taliesin around 3 minutes in.

More on Gertrude Kerbis:

Here’s the blog post that Blasius wrote about Gertrude Kerbis’s career. Kerbis was remarkable. My thanks to Elizabeth Blasius for asking me questions. It was fun figuring it out.

Posted August 11, 2023

The photograph at the top of this post is in The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

1. Preservation Futures “is a Chicago-based firm exploring the future of historic preservation through research, action, and design.”