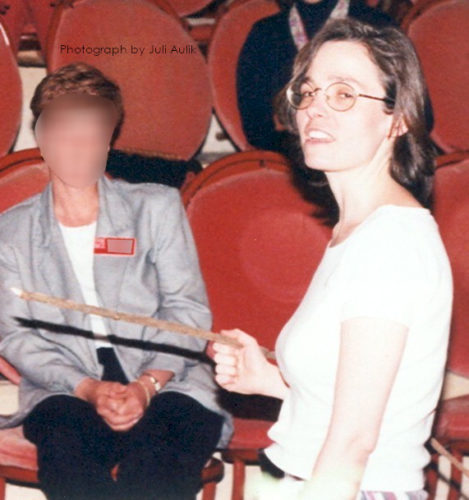

A photograph of me taken by the Executive Director at Taliesin Preservation in 1998. I was giving a lecture on Taliesin’s history.

I talked about “Hey Keiran” in my blog post on “How I became the historian for Taliesin.”

Back then, the only way people got their weekly schedules was to pick up the printed ones at work.

Craig, at that time the head guide, thought a weekly question/answer section would remind people to pick up them up. They called it “Hey Keiran!” and printed them on the back of the schedules.

I thought it was called “Hey Keiran!” because people would ask me things all the time while I was walking through the main floor. Yet someone recently reminded me that the name was inspired by what Dan Savage wanted to call his question-and-answer feature1 at The Onion satirical newspaper.

“Hey Keiran!” is the reason why I’ve contemplated what side of the bed Wright slept on,2 if he knew Feng Shui,3 and whether or not Taliesin had outhouses.

Here are two Hey Keiran Q-and-As that I think are pretty cool. They were too short to write a whole post about, but I thought they deserved to be enjoyed by the masses.

Note that I’ve edited the Hey Keirans for clarity, etc., etc.:

Another geek adventure

until your questions bathe me in the sweat of hardworking researchment (or I figure out answers to questions you’ve already asked), I’ll give you this:

So,

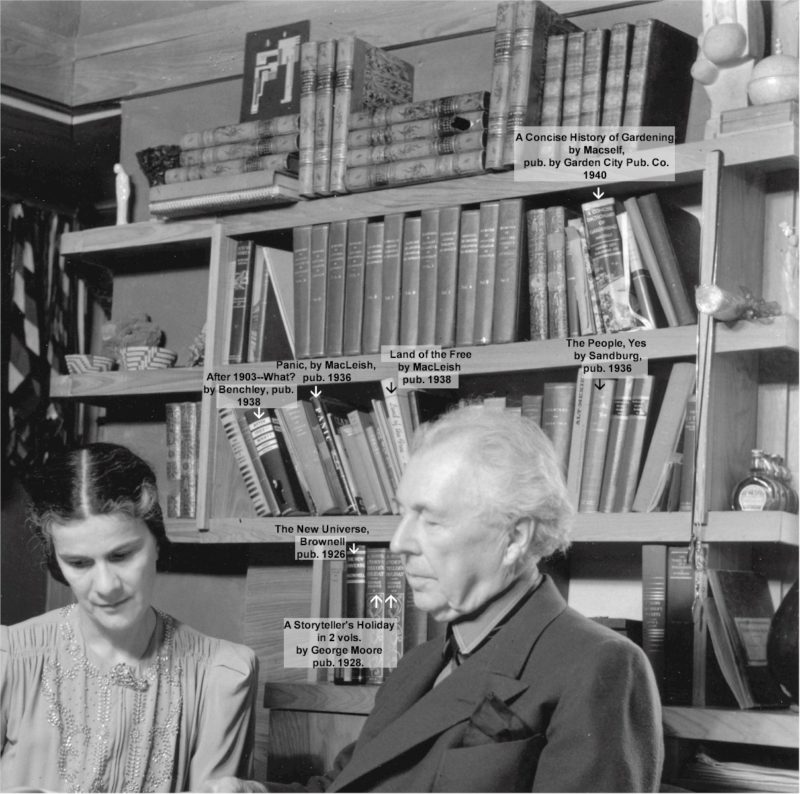

we have a copy of a photograph that shows Frank Lloyd Wright and Olgivanna reading in his bedroom, in front of his bookshelves.

Melvin E. Diemer took it after FLLW moved to the room in 1936, but before he expanded the room in 1950

(I know this because the bookshelves show a slightly different configuration than what existed after he expanded the room).

So, the general date for the photo was 1936-1950.

But then

I had some time before Thanksgiving. And you know me when I have time to think about photos.

In this case, I was musing and thought,

“Hey, Keiran! The photo shows books on the bookshelves – maybe you could look them up and get a better sense of the photograph’s date?”

[btw, I talk to myself like this all the time. Oh, and there’s a bridge I want to sell you.]

Therefore, I took the time to look on-line for the titles of the books. I found some of the books and, as a result, came to the conclusion that this photograph was taken sometime between 1940-1950. Yay!!!!

Here’s the gold, people:

©Wisconsin Historical Society—Deimer Collection, #3976. Please don’t copy this on a large scale, but it is on their website.

What I could read is below:

The New Universe, Baker Brownell, pub. 1926,

A Storyteller’s Holiday (2 vols.), by George Moore, pub. 1928,

The People, Yes, by Carl Sandburg, pub. 1936,

After 1903—What?, by Robert Benchley, pub. 1938,

Panic, by Archibald MacLeish, pub. 1938, and

A Concise History of Gardening, by A.J. MacSelf, this ed. pub. by Garden City Pub. Co., 1940.

At the time that I wrote that Hey Keiran article, the book, After 1903—What? was in the room at Taliesin known as the Garden Room (someone took a photo of it, here).

I mentioned that in the Hey Keiran article:

I freaked out on a tour

(in a good way)

when I looked down and saw this book. Donna

(the House Steward working that day)

seemed to handle it ok. I think that is because she’s used to me coming into Taliesin and finding odd things that I get really excited about.

Ok.

Here’s another Hey Keiran!

This is the question:

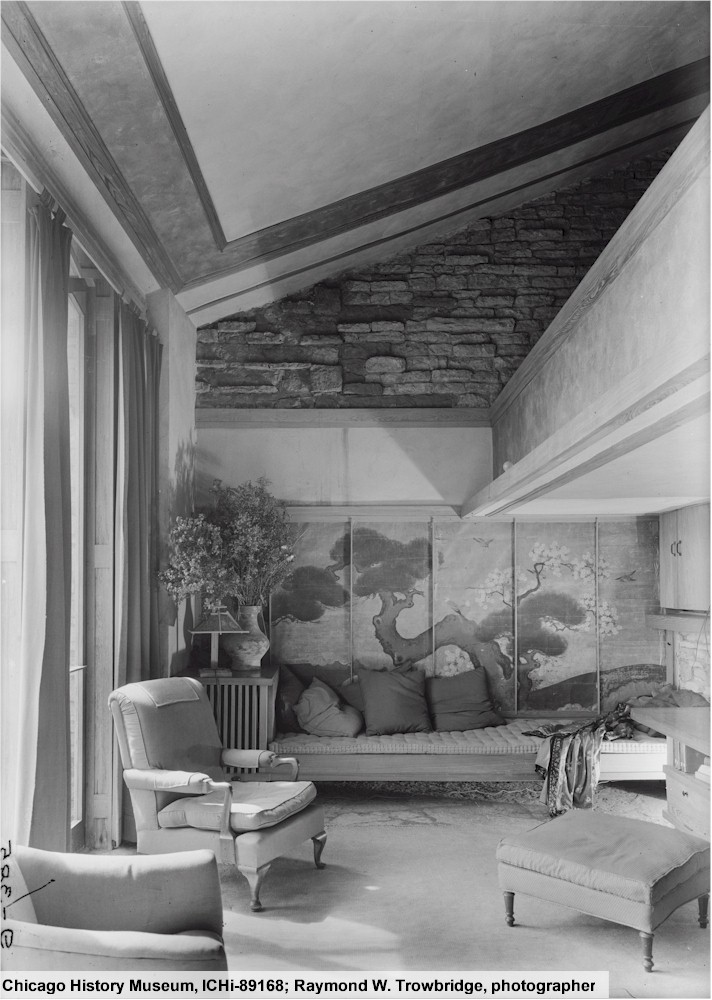

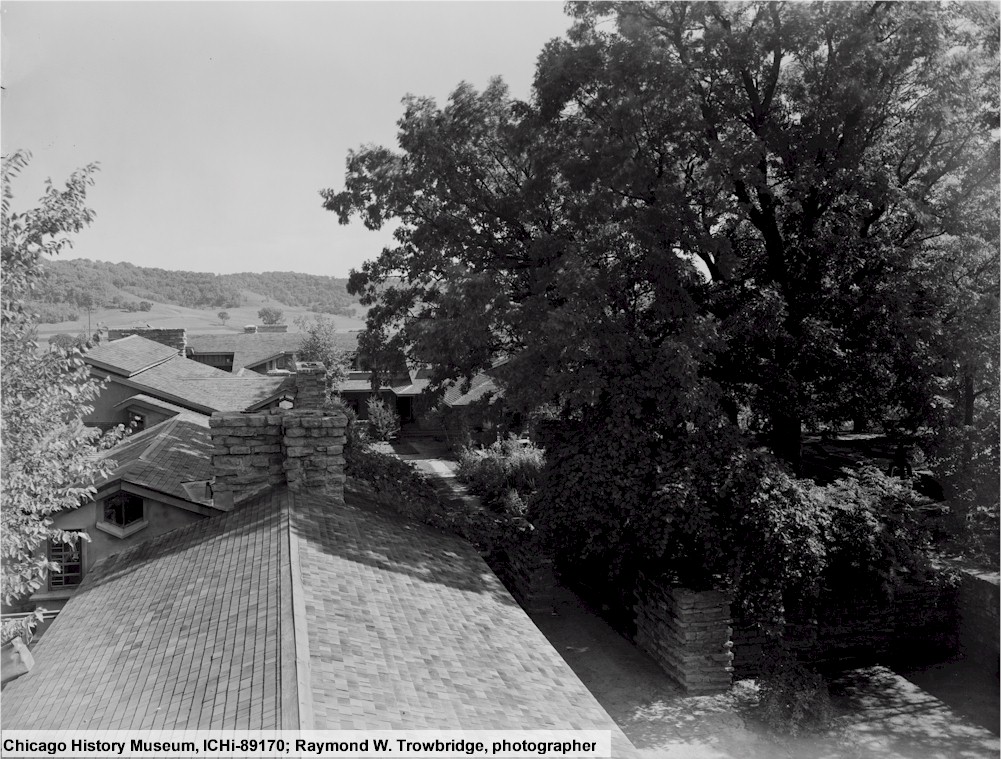

Q: When was the portrait of Anna Lloyd Wright put above the fireplace in Wright’s studio? Originally, Wright had an Amida Buddha painted on a 3-part screen—if I’m interpreting an old photo correctly. What happened to that? Sold? What was up there when he died?

Here’s my response:

A: Anna’s portrait was up there when Wright died. Initially, we were told that Wright put his mother’s portrait up there when it was painted.

So we thought he put it there c. 1920.

However,

when I began looking at historic photographs, I couldn’t find evidence of that.

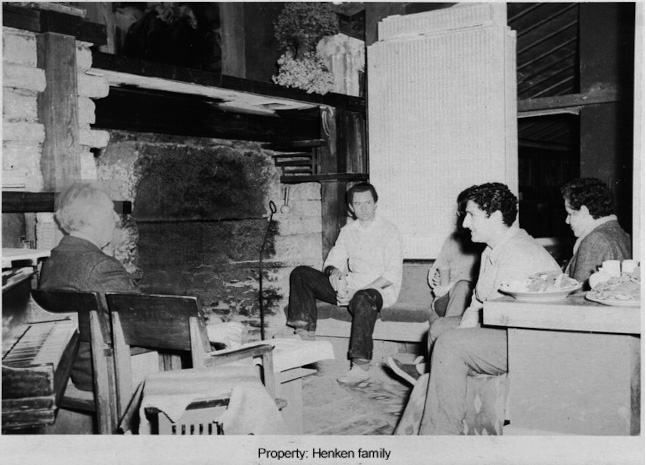

In fact, a couple of photographs clearly show the Amida Buddha, and those photos date from the late 20s-early 30s.

(so, before the Taliesin Fellowship started in 1932).

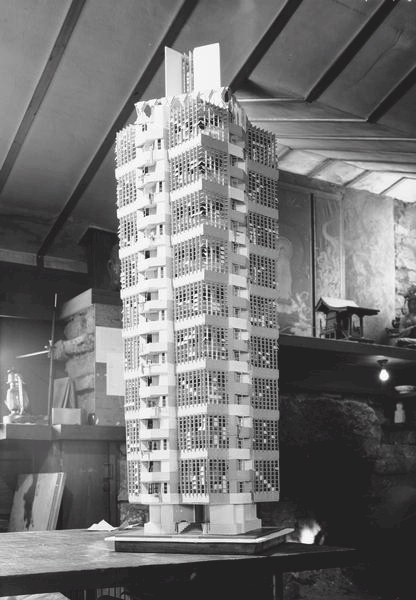

One of those photos is on the Wisconsin Historical Society website. That photo is below:

Photograph from the Wisconsin Historical Society.

Collection: Frank Lloyd Wright Projects Photographs.

You can see two panels of the Amida Buddha screen in the background.

So, when did Anna’s portrait get up there?4

Former apprentice, the late Kenn Lockhart, answered that question in an interview with Indira Berndtson

(she is the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Administrator of Historic Studies: Collections and Exhibitions)

Indira interviewed him at Taliesin on July 27, 1990, and he talked about the painting. Lockhart, who entered the Fellowship in 1939, said in his interview that:

“I have an idea that one of his relatives had it and it came. Because I remember when it arrived. We were living here [i.e., at Taliesin] during the [second World] war.”

Here’s a photograph of Lockhart sitting in Wright’s studio, on the built-in seat by the studio’s fireplace. Priscilla Henken likely took the photograph in 1942-43:

Photograph in Taliesin Diary: A Year with Frank Lloyd Wright, by Priscilla Henken. Page 107, bottom. Lockhart is in the middle of the photo, facing the viewer. Frank Lloyd Wright sits on the far left. The apprentices David Henken, Curtis Besinger and Ted Bower sit on the right.

Wright did not sell The Amida triptych. After he removed the triptych from that wall, he put it into storage. I know that because it doesn’t appear in other photos of Taliesin interiors while he was alive. At some point, the Taliesin Fellowship brought it down to storage at Taliesin West in Arizona.

The screen was restored in the 1990s. The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation sent it up here for viewing one summer in the late 1990s, but it didn’t go where Anna’s portrait is. After that summer, the screen went back down to T-West and has been occasionally shown at the Phoenix Art Museum.

So, that’s it.

Ultimately, I wrote hundreds of “Hey Keiran” pieces. Most were only one-page long. However I did mess with font sizes and such to get them to stay on one page.

I’ll add other things when they fit here and there.

First published August 23, 2022.

This photograph was taken when I was around 30 years old. As I recall, I was answering TPI’s Executive Director (Juli Aulik) on how I was going to uncover all of Taliesin’s history. . . . Still workin’ on it.

Notes

1 Savage wanted to call it “Hey Faggot!”

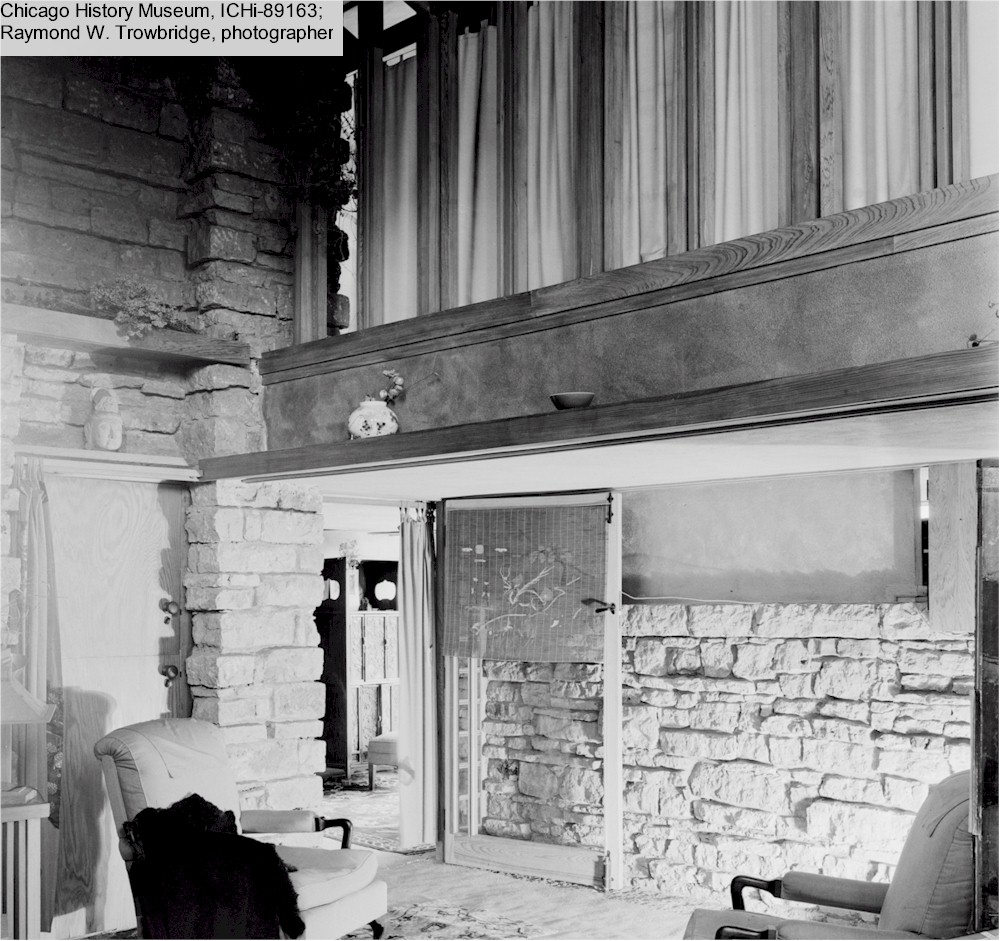

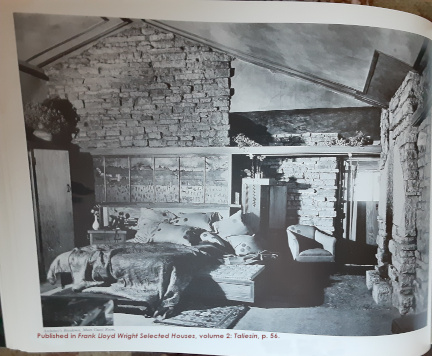

2 After analyzing a couple of photos, I concluded that Wright might have slept on the left side of the bed (like the photo below),

then switched to the right side of the bed (like in the photo here), which is just INSANE.

3 After rejecting the idea for years, I think he might have realized something about it. Although I still don’t think he “studied” it.

4 The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Administrator of Historic Studies reminded me that I do know the answer now on when Anna’s portrait came to Frank Lloyd Wright’s Drafting Studio at Taliesin. Kenn Lockhart was correct: this did have to do with Wright’s family. The painting is by John Young Hunter, and Indira looked up correspondence Hunter had with Taliesin. The painter knew Wright’s sister, Maginel, and asked her if she was interested in the painting. Wright ended up purchasing it, and it was sent to Taliesin in 1939. [confirmation of it was sent in correspondence H053E09.]