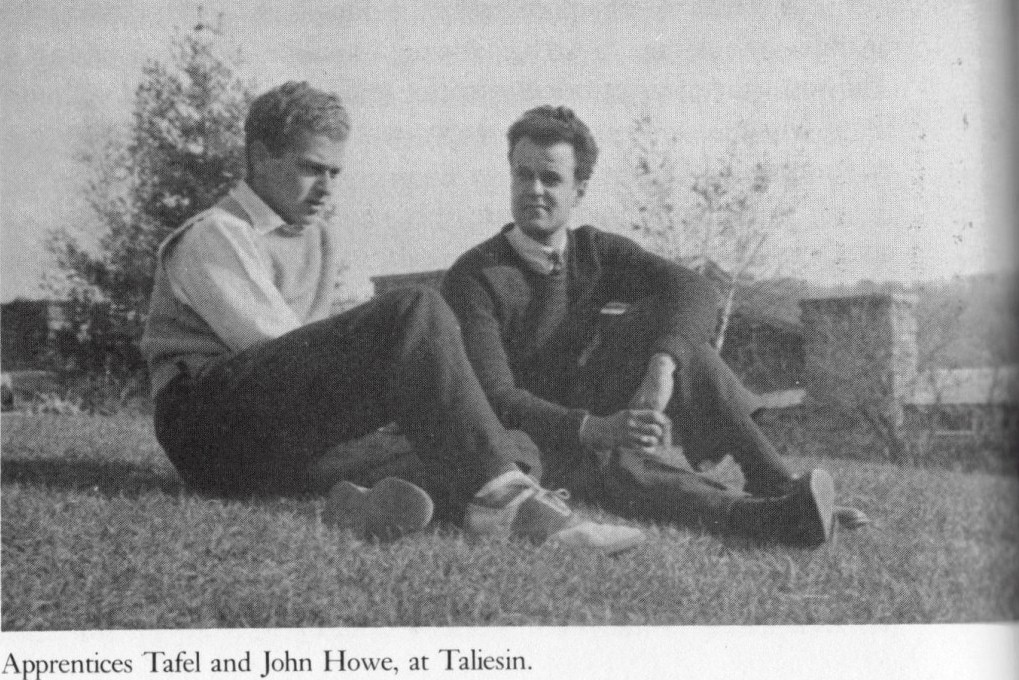

Apprentices Edgar Tafel (left) and Jack Howe (right) sitting on Taliesin’s hill crown. Wright’s bedroom is to the right of Howe’s left elbow.

“You’ve made it,” I whispered to myself. At the far end of the room, on a raised platform serving as a stage, stood Mr. Wright. It was like coming into a presence. And what presence he had! He shot out electricity in every direction.

Near him were a grand piano and an old wind-up phonograph screeching out a Beethoven symphony. He was testing the acoustics. I crossed the room, still holding my breath, and said, “Mr. Wright, I’m Edgar Tafel. From New York.”

. . . . “Young man,” he addressed me, “help move this piano.”

Edgar Tafel. Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius (1985; Dover Publications, Inc.; McGraw-Hill Book Company, New York, 1979), 19-20.

At first, I thought about recommending the book, “Understanding Frank Lloyd Wright’s Architecture“, by Donald Hoffmann, because it talks about the specifics of Wright’s design. But what would I recommend to someone who has no idea who he was, and why they should care? What book out there explains him, and is a bit fun? Finally, this book came to mind: Years with Frank Lloyd Wright: Apprentice to Genius , by Edgar Tafel.

The author of “Apprentice to Genius”, architect Edgar Tafel (March 12, 1912-January 18, 2011), apprenticed under Frank Lloyd Wright in the Taliesin Fellowship for nine years. Then, in the early 1970s, he began lecturing on his experiences in the Taliesin Fellowship, developed this book and published it in 1979.

Hold on: I should explain the Taliesin Fellowship.

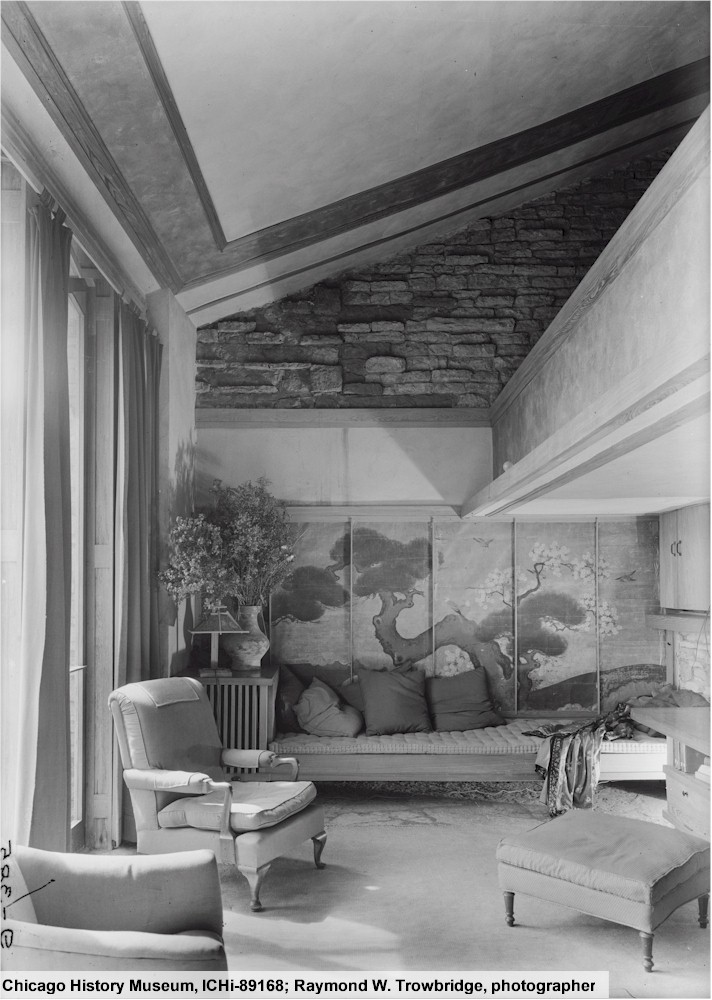

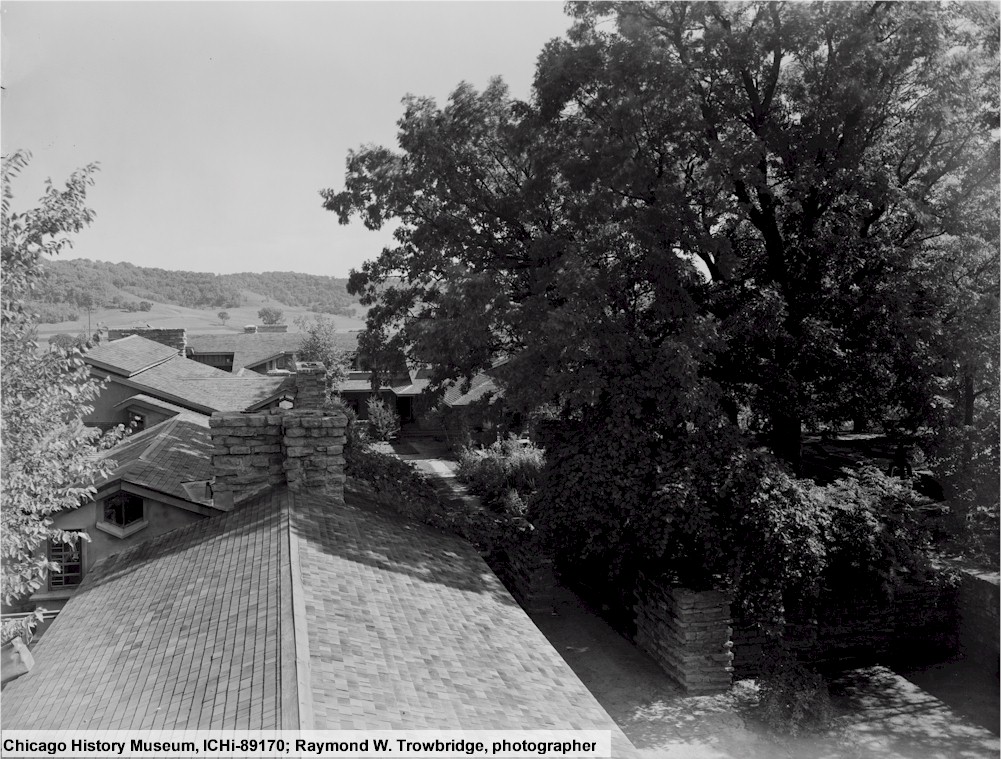

You can’t look at Wright after 1932 without taking the “Fellowship” into account. Wright and his wife, Olgivanna, founded the Fellowship in 1932. Wright, 65 years old at the time, had only completed two commissions in the previous eight years. Encouraged by his wife, the two created an apprenticeship program with himself as the master architect. Open to men and women, apprentices would live on site with the Wrights at Taliesin in Wisconsin. Eventually, the apprentices would live in almost all of the buildings on Wright’s Taliesin Estate. Not a commune, they comprised a community that participated in almost every daily aspect of the life of Frank Lloyd Wright and Olgivanna. They worked in construction, had social activities (such as making music), did all-around maintenance (heating, plumbing, etc.) as well as garden and farm work, all while also working in the drafting studio.

In 1937 (after spending several winters in Arizona with the group), Wright bought land in Scottsdale. He and the Fellowship began building a winter compound there: “Taliesin West“. The construction of Taliesin West led to a yearly “migration” between the two compounds: Wisconsin in the spring-summer-fall, and Arizona from late fall to early/mid-spring. (I mentioned these migrations in my blog post, “Did Wright ever live in Wisconsin in the winter?“)

Oh, and I should mention: apprentices paid tuition. Tuition in 1932 was $650, but Wright took $400 from Tafel, because that’s all the young man could afford.

The first book by a former apprentice:

“Apprentice to Genius” was also the first book on Wright that I read when I started giving tours in 1994. Tafel, 20 years old in 1932 when he became an apprentice, stayed until 1941. When Tafel arrived, Wright had only completed two buildings in the previous eight years. Whereas, by the time Tafel left, Wright was becoming nationally famous. He was the architect for (among many other buildings) Fallingwater in Pennsylvania, and the world headquarters for Johnson Wax (Johnson Wax Administration Building in Racine, Wisconsin).

One of the world’s most famous houses, you saw a photo of Fallingwater on my blog post last week; and, if you’ve never seen the “Great Room” of Johnson Wax, click the hyperlink for the Administration Building, because it’s incredible.

On top of that, Wright had appeared on the cover of Time magazine.

“App to Gen” was the first book-length publication on what it was like in the group with Wright as its leader. Woven throughout the book is a biography on Wright, an explanation of the architect’s philosophy of design, and stories of the every day life of the Taliesin Fellowship. Tafel took time to write about how he cared for Wright, and why.

Tafel’s book:

- Showed Frank Lloyd Wright’s humor, passion and intelligence;

- Told the story of the lean years of Wright’s Taliesin Fellowship, the start of the desert compound, and the start of Wright’s career resurrection;

- Showed these young men and women, 18-24 years old, acting like goofballs with the Wrights mostly allowing it (although Wright did force a tablespoon of castor oil on Edgar1 the morning after Edgar drank too much);

- Published unique photographs from Tafel’s own archive;

- And told the Fallingwater story.

The “Fallingwater story”

The story is that Wright drew Fallingwater, one of the world’s most famous buildings, in two-and-a-half hours while the client drove to Taliesin.

There are arguments on whether the story actually happened the way Edgar told it. In fact, those also in Wright’s drafting studio that day continuously argued in good humor about the story’s truthfulness, probably for the rest of their lives.

But did Wright actually take crisp pieces of paper and, for the first time, delineate a masterpiece while the clients drove to his home? Some said that he had sketches for the design and that’s what he presented to the client, Edgar Kaufmann, Sr.; not the beautiful presentation drawing of the home over the waterfall on the cover of Time. Regardless, as Wright told his grandson one time: “It makes a great story.”2

An overview of the Fallingwater story is in the Wikipedia page on Fallingwater and in the Post-Gazette (with a paywall).

Lastly, on the book and its author:

The book, printed by Dover publication as a paperback, was sold for years—decades—at $12.95 or so. Edgar Tafel autographed my paperback version when he came to Taliesin in 2005. The paperback is still available, mostly through Amazon.com, but I later bought the hardcover original through www.abebooks.com. My hardcover came for only about $18, delivered. That version also has some of the book’s photographs in color, which was a nice surprise.

Edgar Tafel was interviewed in the documentary on Frank Lloyd Wright by Ken Burns (the documentary that led my friends to say, “I Never Knew He was Such an S.O.B.!“).

Here are further appearances by Tafel on YouTube:

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Juh9rB53Mxg

- Edgar speaking about Wright and the Fellowship during its 60th reunion.

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Jfh2MqW63t8

- Tafel at Fallingwater with Fellowship member Wes Peters.

Next week I’ll give a list of books by former Taliesin Fellowship apprentices. But for now, here’s a link to the Taliesin Fellows, an organization of former apprentices.

Originally published March 27, 2021.

The photograph at the top of this post was in “Apprentice to Genius,” page 38. The photograph is now in the Edgar Tafel architectural records and papers, 1919-2005 in the Avery Drawings and Archives Collection.

1 Most apprentices in the Fellowship were known by one name; usually not their last name. So, you weren’t a private in the army; you were part of a community. This did sometimes lead to people going by names other than what they were born with (or known by) before walking in. Although I don’t know how many “John”s or “William”s had to change their names to something else.

2 And yes: I did actually really hear his grandson say that. Brandoch asked his grandfather about one of the apocryphal Wright stories (I’ll tell you some time). He said his grandfather replied that [more-or-less], “did I say that? I don’t remember saying it. But… it makes a great story.”