The image above is a screenshot from the home page of “The Wayback Machine“, which is explained below.

Here’s part of the explanation of The Wayback machine in Wikipedia:

The Wayback Machine is a digital archive of the World Wide Web. It was founded by the Internet Archive, a nonprofit library based in San Francisco, California. Created in 1996 and launched to the public in 2001, it allows the user to go “back in time” and see how websites looked in the past. Its founders, Brewster Kahle and Bruce Gilliat, developed the Wayback Machine to provide “universal access to all knowledge” by preserving archived copies of defunct web pages.

Since its creation in 1996, over 603 billion pages have been added to the archive….

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wayback_Machine

If you’ve never heard of the Wayback Machine on the Internet, you may have come across the phrase from the Rocky and Bullwinkle Show on television, starting in the 1960s (I watched it on Saturday-morning-cartoons). The Rocky and Bullwinkle show had a short cartoon, “Mr. Peabody’s Improbable History”, which featured a Time Machine known as The Wayback Machine.

Mr. Peabody, a talking, genius dog, is the grownup, taking care of a young boy named Sherman. They use the Wayback Machine to go back in time to correct history. Here’s the intro on Youtube:

Luckily I only wasted about 20 minutes finding, then watching, the intro.

Nice. You gonna tell us why you’re talking about this today, Keiran?

Yes. Glad you asked.

The Wayback Machine popped into my head because I was thinking about what to post today and remembered a photo I had previously seen on the Internet.

When I post, I look for photos that copyright rules let me show you all. I thought of this great Taliesin exterior that I got off the internet almost 15 years ago. I got the URL, but couldn’t find the image today.

So I went to The Wayback Machine. I put the URL into their archive, and the photo below came up:

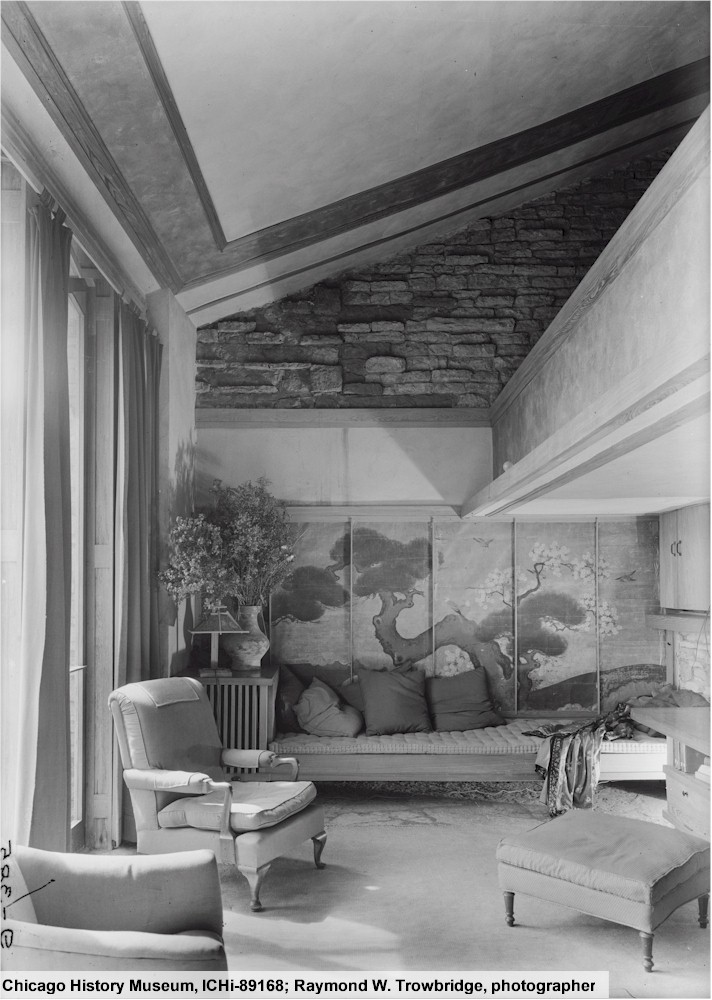

Taken from the Hill Crown of Taliesin, looking (true) east at Taliesin’s living quarters. The unknown photographer apparently took this in the spring, based on the green leaves seen on the oak tree on the left hand side of the photograph. Architectural details indicate they took the photo in the 1950s, before Frank Lloyd Wright’s death.

When I found it, I said, “Behold: The Wayback Machine”

Said, most likely, in stentorian tones and accompanied (again, most likely), by a sweep of my arm.

Immediately after this, I thought I should write about this site as well as this on-line image.

Here’s the image through the Wayback Machine:

You see the name “j_buscaglia” in the location information for the image. I have attempted to locate “Buscaglia”, the person who had uploaded this image when they were, perhaps, learning HTML coding, etc. as a student. Years ago I found an email address for them at Colorado College and wrote them, but they never replied. Moreover, I never found information about the web page or anything else. So this is perhaps an “orphaned” image.

Things I find interesting in the photo:

You can see details to the right of the pine tree (detail, below).

These are the west and south walls of “the Garden Room” in Taliesin’s living quarters. The south wall of the Garden Room has beige/yellow stucco, to the right of the French doors. Next to it is a tree trunk, followed by a limestone pier. The pier supports the edge of the balcony. The beige stucco attracted my eye, because there aren’t many photographs of that wall with stucco.

Before 1959, that wall often had tar paper (as waterproofing)

Look here for another photo of that wall with tar paper. This photo comes from the website of Pedro E. Guerrero, Wright’s photographer.

I don’t know why it took so long before Wright covered the tar paper. Although, in truth, the Guerrero photographs of Taliesin come from 1952-53. While Guerrero took many photographs of Wright and the two Taliesins, he worked on retainer. Wright would send the photographer all over the United States to photograph the architect’s newly constructed buildings. As a result, he could rarely visit just to photograph Taliesin.

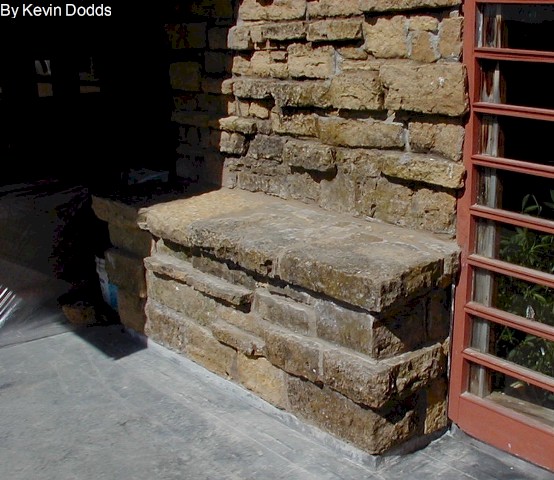

If you were to go to Taliesin on a tour today, you would see that this wall has, not tar paper, but a stone veneer (here’s a photo of it). That veneer was applied by a member of the Taliesin Fellowship, Stephen Nemtin. He joined the Fellowship as an apprentice after Wright’s death and was asked to do this by Olgivanna Lloyd Wright, the architect’s widow.

I don’t know why the Fellowship veneered the stucco with stone. Maybe the stucco got too wet in the rain, ice, and snow.

Here’s the detail from that color photo again:

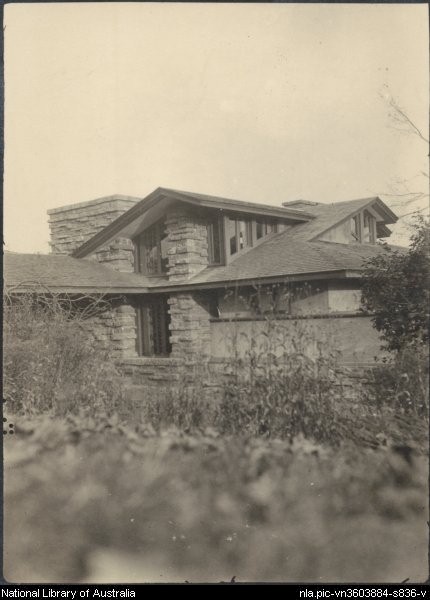

The photo has a white, almost-vertical line underneath the balcony. That line is the trunk from a birch tree that used to grow there. That tree was originally one of a pair. The photograph below shows those two trees. I took this photo from my copy of the book, Wisconsin: A Guide to the Badger State, printed in 1941 as part of The American Guide Series:

Photograph looking (true) east from Taliesin’s Hill Crown towards its Living Quarters. The birch trees are in the center of the photograph. The roof on the left was later over the Garden Room.

Finding my version of the image:

This book was part of the Federal Writers’ Project. It was a project of the Work Projects Administration in the state of Wisconsin and was sponsored by the Wisconsin Library Association. I took this image from the book, in its photographs between pages 310-311.

The Wisconsin Historical Society has the original image, on-line here.

I found this image, and the book, during another on-line photo-searching project of mine one Friday.1 After finding out about this photograph, and the book in which it was published, I bought the book via abebooks.com.

The book has, among other things, descriptions of driving tours one could take at that time around Wisconsin. The “Madison to Richland Center” drive is “Tour 20”. The book’s write-up gives a brief history of Taliesin, as well as telling you that you can take a tour at Taliesin (really, the Hillside Home School) for $1. In addition it tells you that you could take in a “moving picture, Sun. 3 p.m., included in tour fee; otherwise 50¢ per person.“

The birch trees grew there over 15 years, but Wright’s expansion of the room above killed them: the new construction meant that the trees now grew through an interior room. Perhaps he did this just because he wanted to see the effect (and not worry about killing them). In fact, this was not the first time Wright’s expansion of his home killed a tree: his expansion at his first home and studio in Oak Park, Illinois, resulted in the death of a Willow tree.

I hadn’t planned it, but it seems that we stepped into an example of what Bertrand Goldberg characterized as “romantic kitsch” at Taliesin (relayed in my post of May 17, 2021).

Originally published on September 9, 2021.

Notes:

1 I wrote in early December, 2020 about some of my photo searching.

Some ouroboros for you:

Shortly after I posted this, the Internet Archive recently sent me a link to a 2:04 min. video from 1996, in which the Internet Archive staff explained the newly-created Wayback Machine.