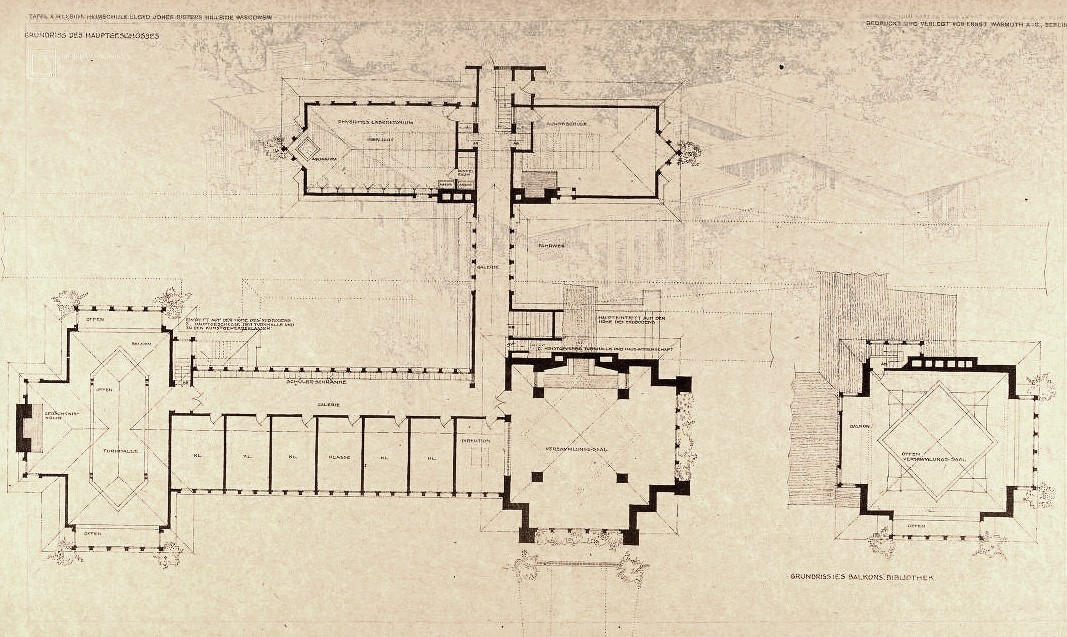

This is a drawing of a building that Frank Lloyd Wright designed for his aunts and their Hillside Home School. They ran the school, which was south of Spring Green, Wisconsin, for almost 30 years. Wright designed this structure for them in 1901. This drawing was published in 1910.

Previously, I wrote about the project I did with architectural historian, Anne Biebel (principal, Cornerstone Preservation), about Wright’s Hillside structure on the Taliesin estate. This post is going to be about something I discovered during that project, which was a comprehensive chronology on Hillside.

About the project:

The Aunts ran the school from 1887-1915. We tried to look at the total history of the Hillside building, but also the history of the school. Since my job was to gather as much information as possible, I looked at old newspaper articles and had a lot of fun finding old facts, photographs, and drawings.

I tried to be objective about the site

So, when I started, I approached Hillside much as I approach Taliesin when studying it. That meant that I went over everything with a fine toothed comb. However, Hillside was never the same dealio (at least not as he’d originally built for his aunts: 1901-03.). That’s coz, Hello!—they were paying clients. Yes, they were his Aunts and they did love their nephew; but: still. He couldn’t mess around with their building. Not while they still had control of it!

And, because Wright was building this for someone else,

I could trust the Hillside drawings that Wright did for the original construction (unlike those he did for his home, Taliesin).

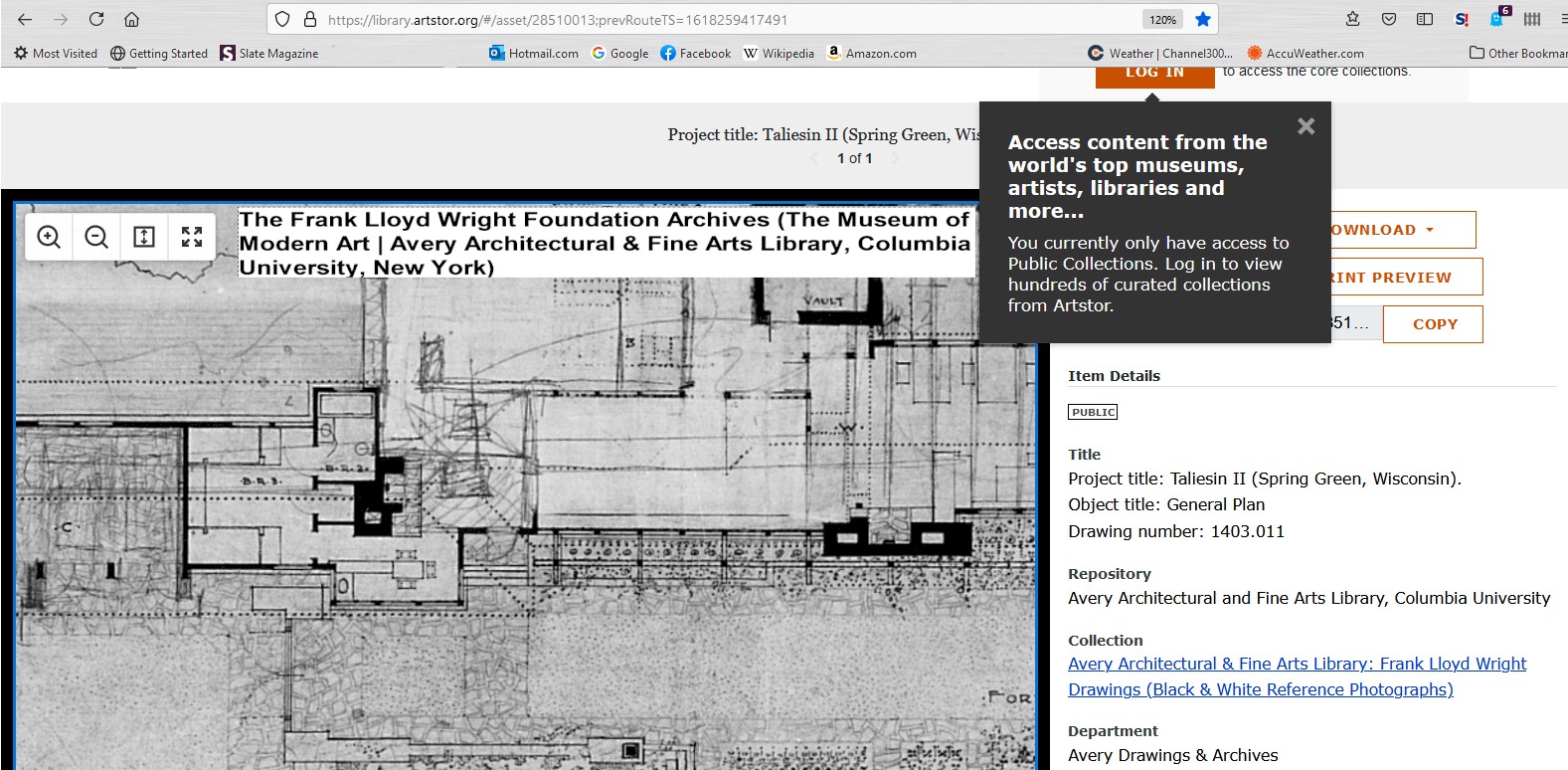

Still, only 12 drawings exist in Hillside’s earliest years. 1 Three more drawings were done later: two were done in 1910 from a portfolio, known as the “Wasmuth”. That’s because the publisher in Berlin was Ernst Wasmuth. The floor plan from the Wasmuth is at the top of this post. I got it from an online version of the University of Utah Rare Books Collection.

Or if you’re feeling fancy, say the full title in German, since it was published in Germany. The original title is Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (“Executed Buildings and Designs by…”).

The last drawing of Hillside was done in 1941 for a retrospective of his work: In the Nature of Materials : The Buildings of Frank Lloyd Wright 1887-1941.

Looking over things:

In the Hillside Chronology project, I studied the drawings like I usually do: I try to look at historical evidence without preconceptions. Otherwise, it’s easy to only see things you want to see, and miss things staring you in the face. So, I looked at the early drawings of Hillside, inch by inch. And…

I finally noticed something

in one of the rooms.

This room, a long room ending in a point, is now known as the Dana Gallery. Look at the drawing at the top of this page. At the top of the drawing is a “T”. The left side of the “T” is the room known as the Dana Gallery today. This room was originally the Science room for the Hillside Home School. The right side of the “T” is another room that’s almost a mirror image of the Dana Gallery. That room, on the right side of the “T”, is now known as the Roberts Room and was originally the Art room.

The names of the rooms (Dana Gallery, Roberts Room) come from two people who gave money to Wright’s aunts when they were completing the building. Wright told the story about the names in the 1943 edition of his autobiography:

One of my clients, Mrs. Susan Lawrence Dana, gave them the little Art and Science building next to the School building and equipment, complete. She loaned the Aunts twenty-seven thousand dollars more to help complete the main school building. Another client, Charles E. Roberts, 2 gave nine thousand dollars to help in a subsequent pinch….

Frank Lloyd Wright. Frank Lloyd Wright Collected Writings, volume 4: 1939-49. Edited by Bruce Brooks Pfeiffer, introduction by Kenneth Frampton (Rizzoli International Publications, Inc., New York City, 1994), 125.

How the Dana Gallery/Roberts Rooms are alike:

Among other things (I’m sure) each room is accessible through 5 steps down from the floor above; has skylights; has a “prow” window (like a triangle coming out of the building) on the end; and a chimney.

Their fireplaces are different, though.

The fireplace in the Roberts Room has a horizontal piece of stone across the firebox. But the fireplace in the Dana Gallery has a design that looks really modern. Even though it, too, is in stone, there are triangles on the design, and either side of it has angles.

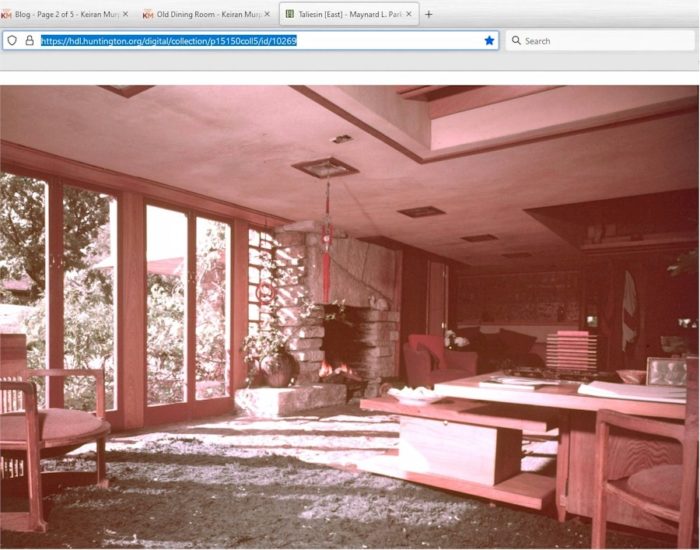

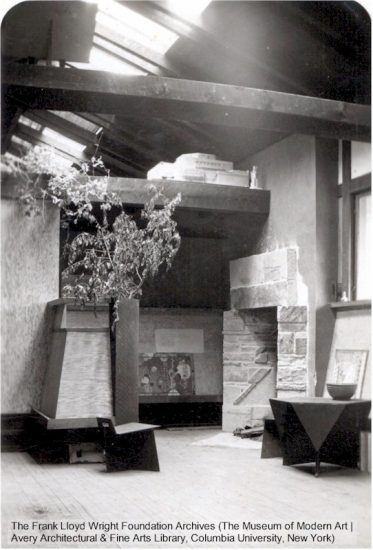

Here’s a photo of the Dana Gallery with the fireplace from The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives:

Unknown photographer. Dated 1936-40. Property of The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), #3301.0008.

The creation of the fireplace was detailed in a December 11, 1936 article in “At Taliesin”, written by Gene Masselink:

. . . . Last summer Mr. Wright commissioned Benny to complete a fireplace in three weeks.

So Benny lugged stone after stone into the Dana gallery. He worked at it at all hours–you could hear him pounding away long after it was dark outside…. The design had been carefully worked out. The lintel was six feet from the floor and the stones were all especially cut to form a pattern on the back of the fireplace. It required skill and some engineering to properly construct the flue. Finally with the help of five others Benny laid the greatest sandstone lintel block. And that night at the celebration in honor of the job, the first fire was built.

Hans, solid German carpenter, declares it would never draw and even as the Fellowship held its breath and as the flames roared up, lighting the room with their best six foot height and the smoke went up the flue out into the moonlit night, Hans still shook his head.

We drank a toast: no one that night prouder or happier than Benny.

EUGENE MASSELINK

Randolph C. Henning, ed. and with commentary. At Taliesin: Newspaper Columns by Frank Lloyd Wright and the Taliesin Fellowship, 1934-1937 (Southern Illinois University Press, Carbondale and Edwardsville, Illinois, 1991), 225, 226.

Due to Gene’s writing:

I figured there had been a fireplace when Wright first designed for his aunts, then Benny redesigned the fireplace mantel to its current appearance. I mean, sure, the Dana Gallery had been the Science room—so maybe flammable things aren’t your first go-to in a design—but, on the other hand (a) the only flammable things I ever saw in my Chemistry classes were the controlled flames of Bunsen burners, and (b) Hillside’s gym also had a running track with a fireplace on the west side.

So, I just figured that those Hillside students weren’t “pantywaists” like I was by the time I was in grade school. 3 I mean, sure! Have open flames around those kids using chemicals, and exercising on the running track!

To get back to the point:

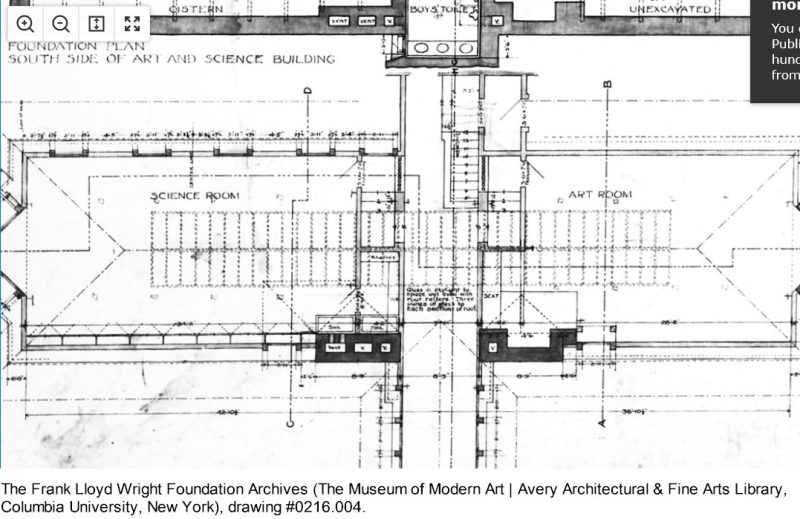

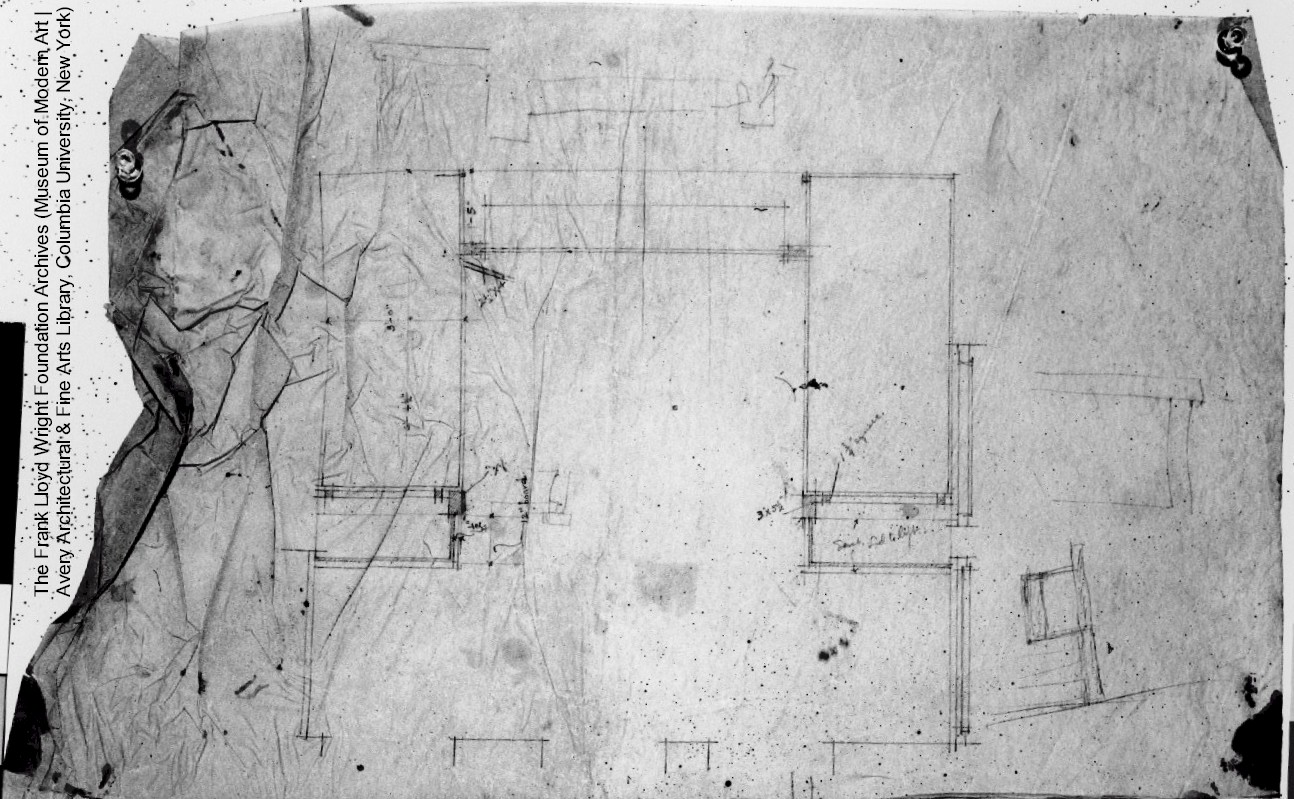

During the project with Anne, I looked more carefully at the Hillside drawings. And I saw, in drawing #0216.004 that, while the Roberts room originally had a chimney, the Dana Gallery did not:

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York), #0216.004.

The chimney on the left had no fireplace, while the chimney on the right did. Looking more closely, the chimney at the Science room had two SINKS in front of it. With a WALL between them. I didn’t know what that was all about.

So, then I thought:

look at the Wasmuth drawing

Because I knew he labelled things in it. Yes, they were in German, and I don’t have a German-to-English dictionary, but there’s Google translate.

So I looked at it. The chimney in the Dana Gallery (the chimney on the left) has this in all caps: DUNKEL RAUM

That means:

Of course!

Hillside was a school out in the country. Teach those kids photography! That’s why there’s a scrapbook of photographs taken of Hillside in 1906, now at the Wisconsin Historical Society.

In fact, the floor of the Dana Gallery has a shadow of the dark room’s wall, which you see in the photo I took, below:

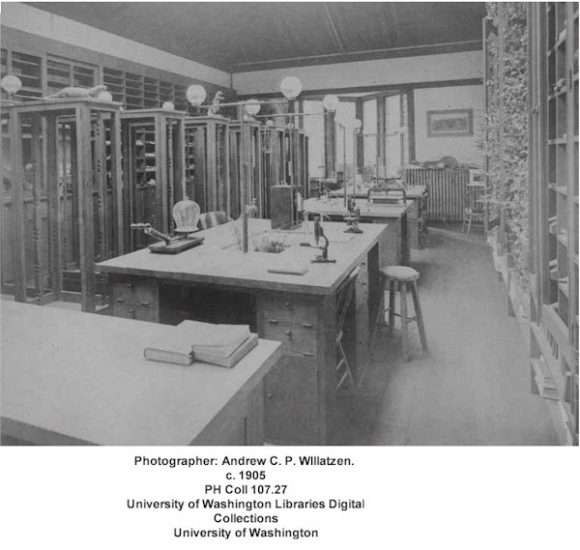

But unfortunately I’ve never seen a photograph showing the walls of the dark room. The photograph below shows you about what’s been seen of the room when the Aunts ran the school. You can see how it was a science classroom:

First published February 9, 2022.

First published February 9, 2022.

The drawing at the top of this post was published in Ausgeführte Bauten und Entwürfe von Frank Lloyd Wright (“Executed Buildings and Designs by Frank Lloyd Wright”) in Berlin in 1910. I’ve put it here in part because I do not know who has the rights to it.

1. I’ve wondered if there were more.

2. This link only brings you to the page on Wikipedia about the Charles E. Roberts Stable (although it tells you a bit about the man himself). There’s no Wikipedia page about the Charles E. Roberts House, though. If you were feeling generous and had the interest or patience, you should write about it.

3. That’s what one of the nuns called us in the 8th grade because we weren’t fighting in the Falkland Islands war. That’s not a statement about Catholic schools; just a statement about a weird moment as a kid. As I’ve gotten older that statement makes less and less sense. In part because we were all American citizens.