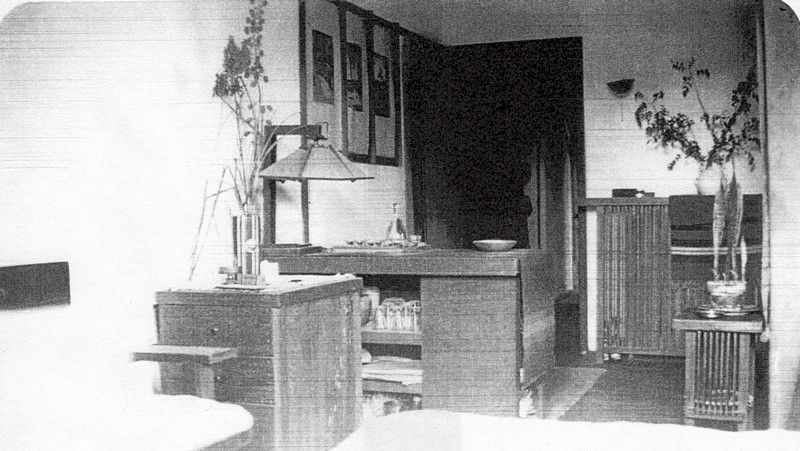

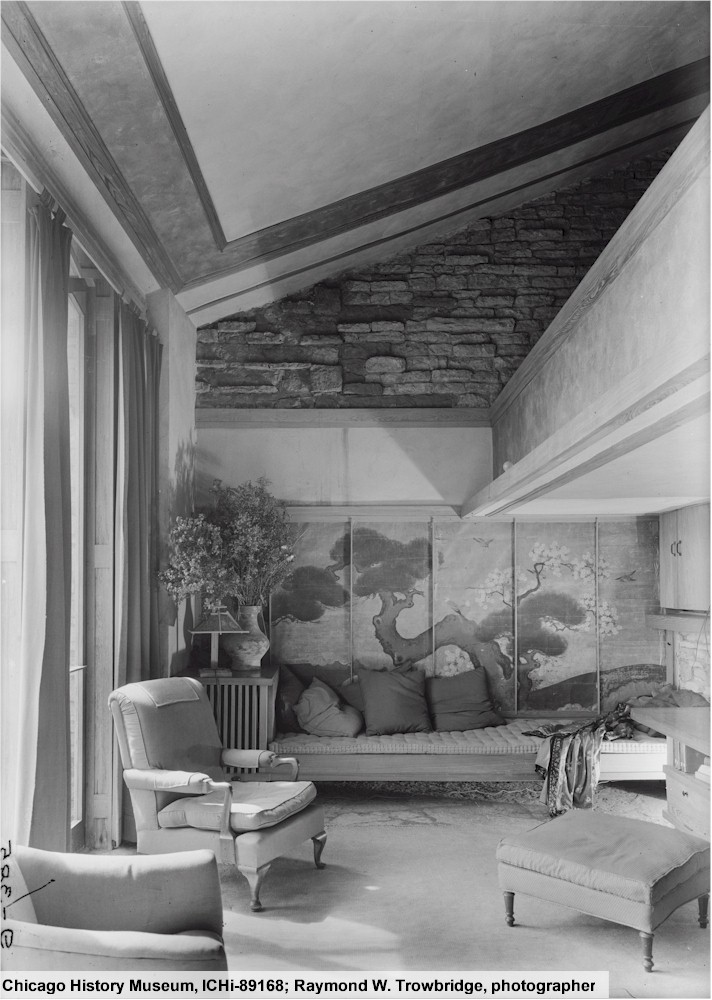

This is a photograph of a room that I spent part of an afternoon contemplating and figuring out.

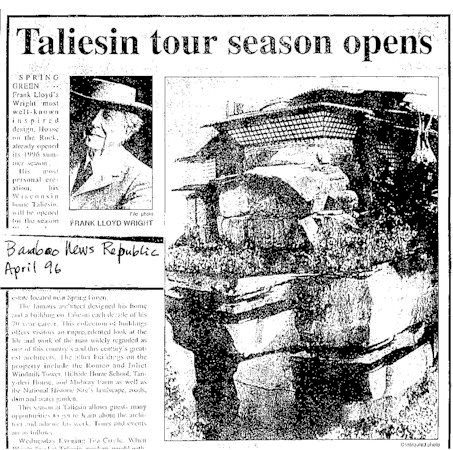

Not this year (we were in Arizona!). No, this took place in the aughts.

Why are you talking now?

Late December/New Years reminds me of something I did before I started my Christmas vacation one year. That is:

I identified a photograph

Seems kind of strange when I put it that way.

“You identified a photo. What does that mean? Did you think it was a Polar Bear Cub before you realized you were looking at a photograph?“

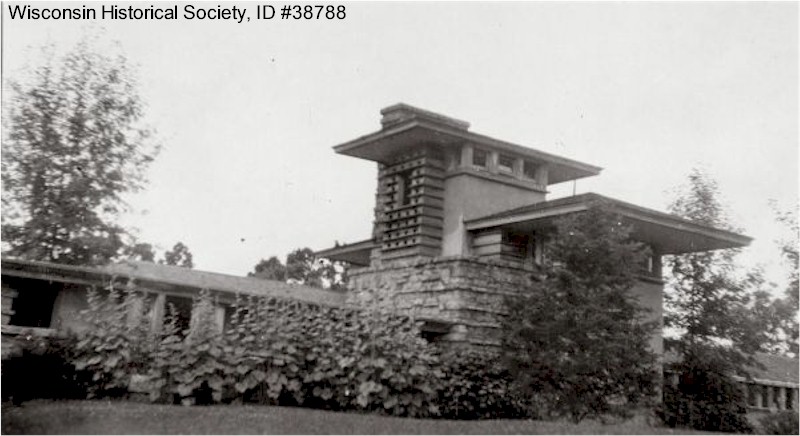

No. I’m talking about a photo taken inside Taliesin, but we didn’t know where. In this post I’m going to write about how I figured out which room the photo was showing.

That’s because, as I’ve noted before,

Wright made a lot of changes at Taliesin.

And while the photo (seen at the top of this post) showed furnishings that indicated it was taken somewhere inside Taliesin, the space no longer existed. At least not the way it was shown.

Earlier, someone else thought maybe it was a photograph of another room, and stuck it in the image binder.

But that also didn’t seem correct.

So, I took it out and put the image in a “to be determined” folder. And it stayed there for years, waiting for a home.

Additionally, this wasn’t the best photo you’ve ever seen. I mentioned before (when I wrote about the dam at Taliesin), how, when I first worked in the office, a lot of the photos were, like, seventh generation Xeroxes. This was close: a printout of a scan of a photo emailed to the Preservation Office in about 1996. It looked kind of like what you see below:

Property: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

The desk lamp you see on the left is all over Taliesin, and the woodwork looks like Taliesin, too. But nothing else looked familiar. The room had light walls and a flat ceiling. But I didn’t recognize anything through its open door (the black rectangle you see). Also, the configuration—wall, door, and radiator, maybe, to the door’s right—didn’t fit anything that I knew.

So I kept this small printout in a pocket in one of the binders, for years. Then, one time I had a few hours before I took off for Christmas. So, I decided to look at it closely. Perhaps I could figure out what room the photograph showed.

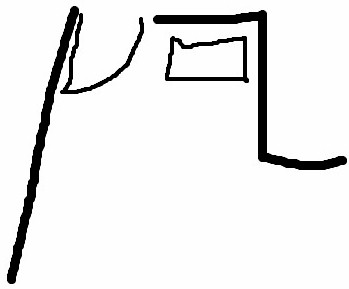

So, I drew it

When I write that I “drew” it, I don’t mean like some super, well-trained person who can depict what they see.

You know, like when you go to someone’s apartment and they say, “It’s such a mess,” and it’s, like, immaculate?

Well, when I say my place is a mess it is, really, a mess.

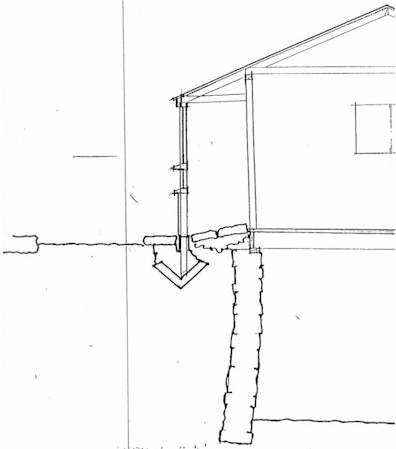

That is, I wrote drew a straight line on the left (denoting the wall), a door that opened in, maybe a radiator, and what looked like a wall on the right that took up part of the room. Here’s an approximation:

The line on the left is the wall. The pointy thing at the top of the wall is supposed to be the door, and the slight arc is the arc of the door that you see in good drawings. The distorted rectangle is the radiator. The bulge on the bottom right is supposed to be the wall corner.

I’m sorry it doesn’t have the brilliant MS Paint work of Allie Brosh in her “Hyperbole and a Half” website, but it will do.

I took that shape (and the knowledge of changes at Taliesin), and—after checking to see that it wasn’t showing Hillside (where people also lived on the Taliesin estate)—I walked through Taliesin in my head.

From basically c. 1925-1959.

So, from Taliesin’s second fire, until Wright’s death. While more people had color film by the 1950s, many did not, so I harbored the possibility that the photograph came from that decade. And, since the image might have been reversed, I had to flip it back and forth in my head.

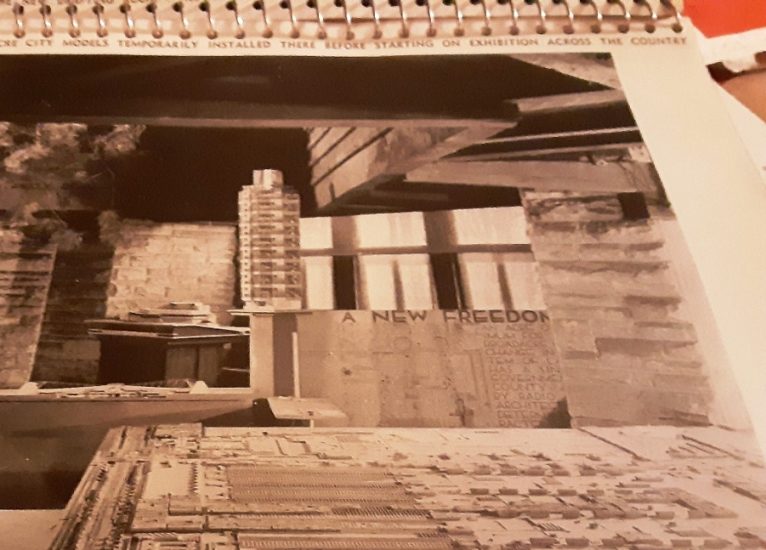

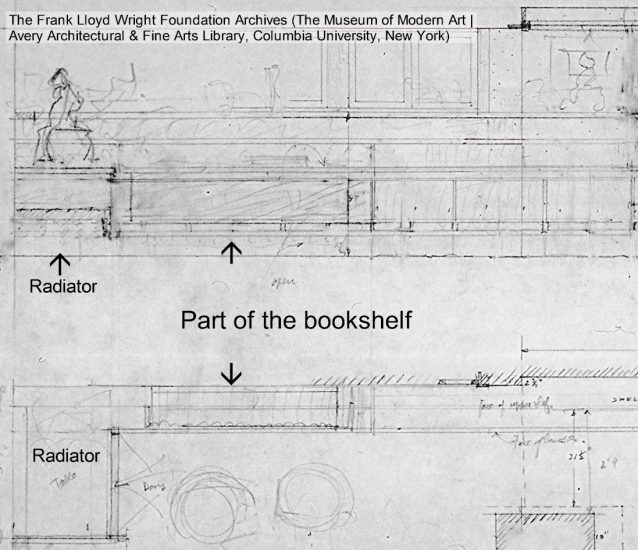

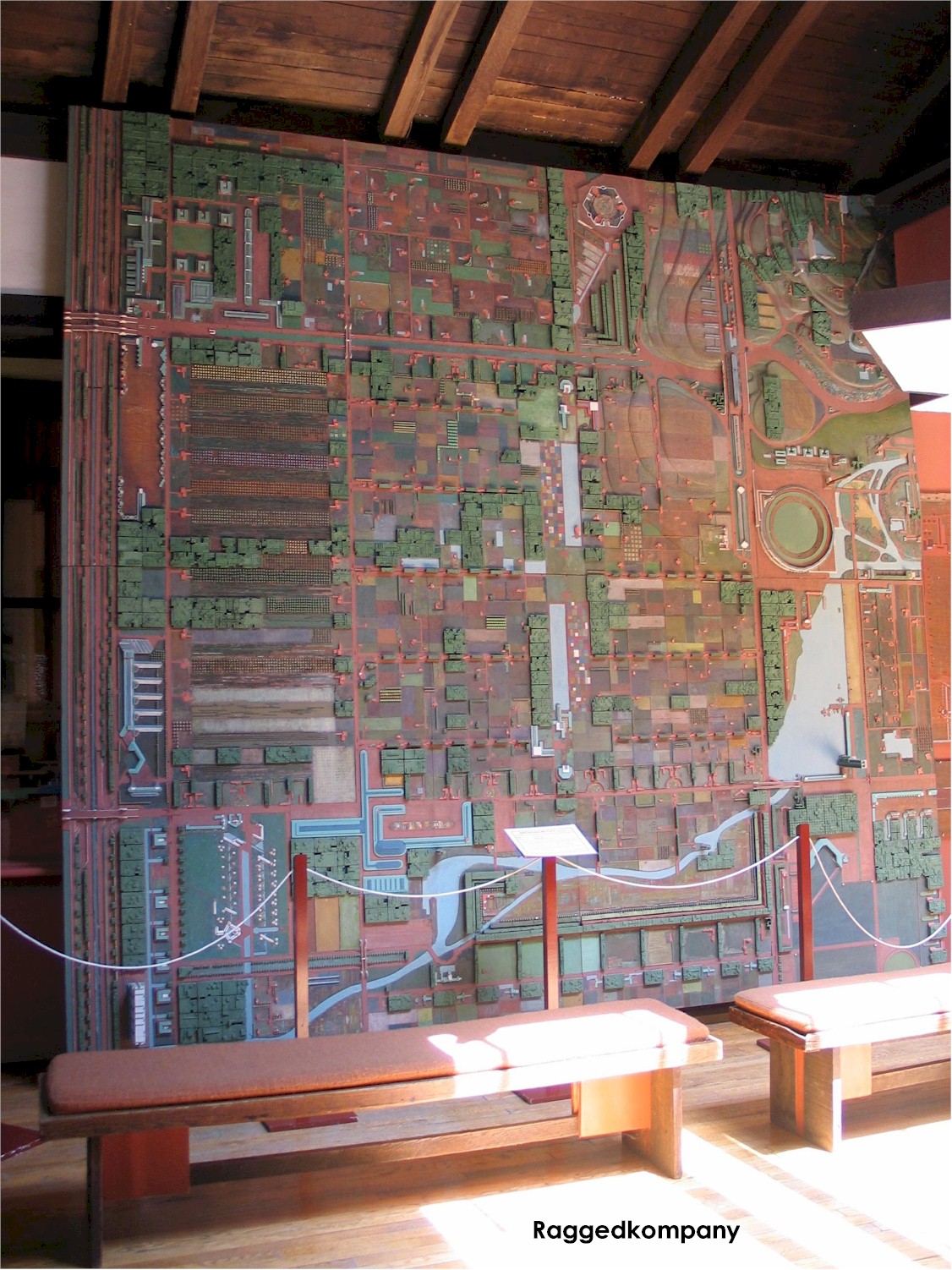

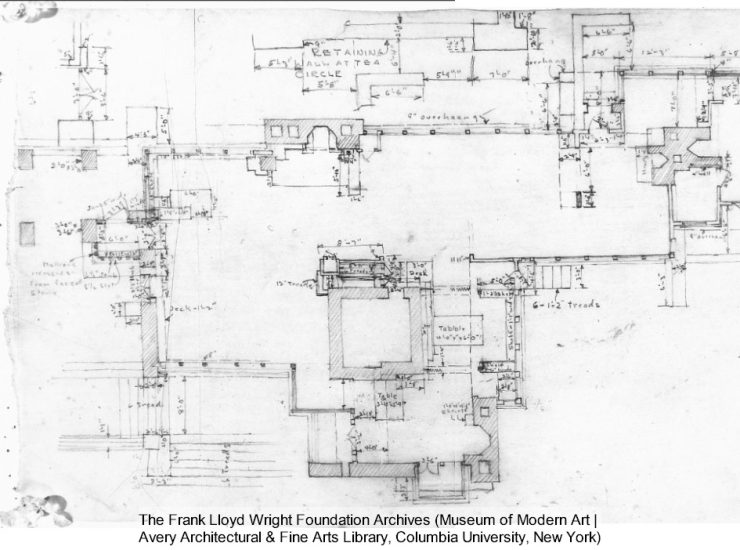

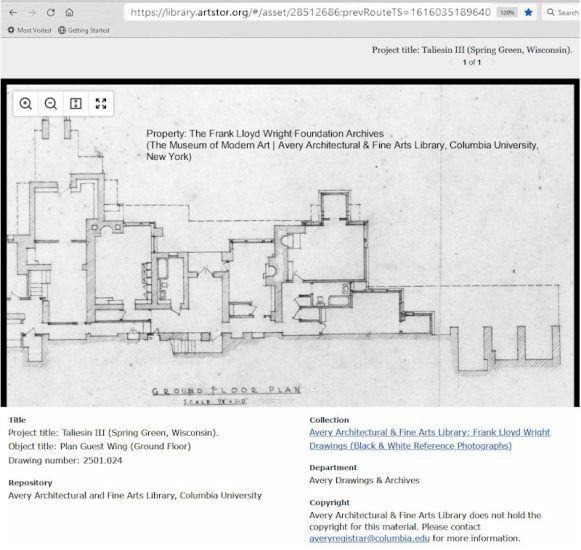

Now, I think it’s best for all of us that I don’t remember exactly how I came to concluding that I was seeing, possibly, one particular room. But, OMG! I found it! In an old drawing. It’s drawing #2501.024, at JSTOR, a cropped version of which I’ve put below:

Property: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York).

What does the drawing show?

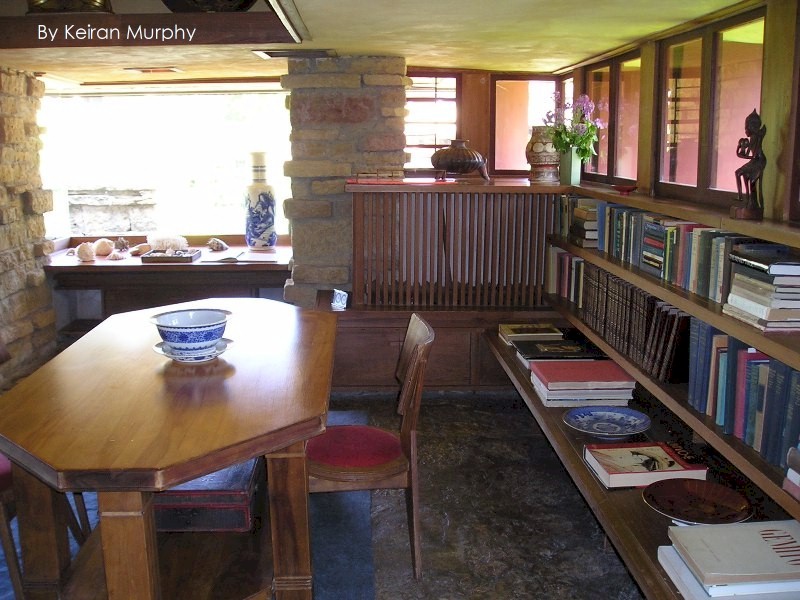

This shows the floor beneath where the Wrights lived at Taliesin. The drawing was executed 1936-39. The room I was seeing in the photograph shows up in the drawing, as the last large room (with a closet) on the lower right. This room is known as the “Blue Room”.

(members of the Taliesin Fellowship were asked about the name, and they didn’t know or couldn’t remember why it was called that).

I can tell you that I checked out the length of time it had taken me to figure which room was in the photo: 2 hours and 45 minutes. I wrote an email to two members of the Preservation Crew, gave them the salient details, I asked them what they thought, then closed up the office and left for Christmas.

They agreed with me

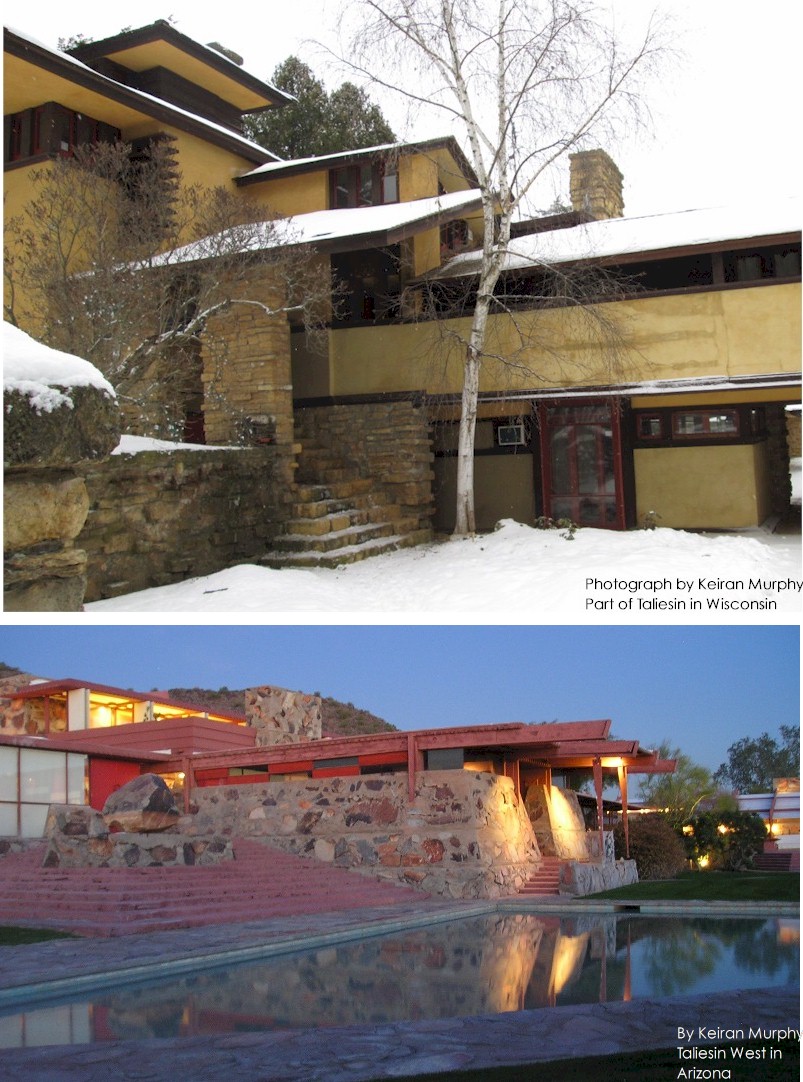

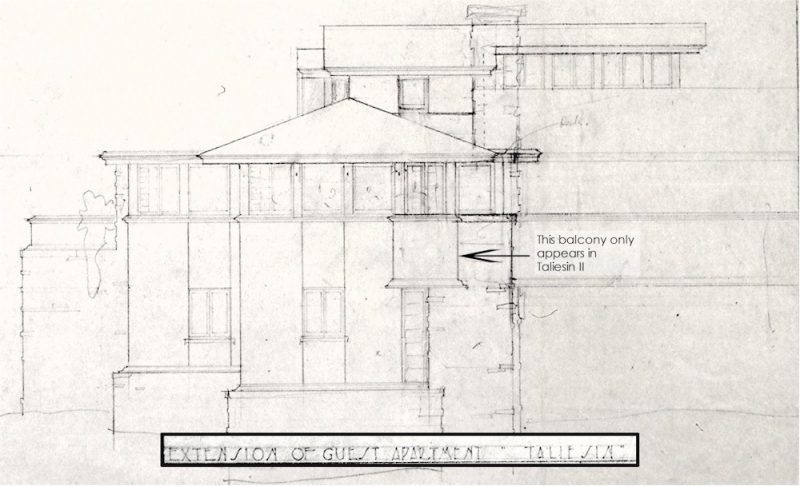

One (Tom) thought that a closet built inside the room (even though there was already a closet) was built in 1943 to take the weight of the changes above. The changes in 1943 were made to a room two floors above.

The Preservation Crew, after getting done all of the work down here (as I wrote about in “A Slice of Taliesin“) finished restoration/preservation/reconstruction. The area where they worked is a zone of Secondary Significance; meaning they can change things if need be. So, the preservation of the room allowed the crew to take out the closet. It was no longer needed because they transferred the weight using added micro laminated beams.

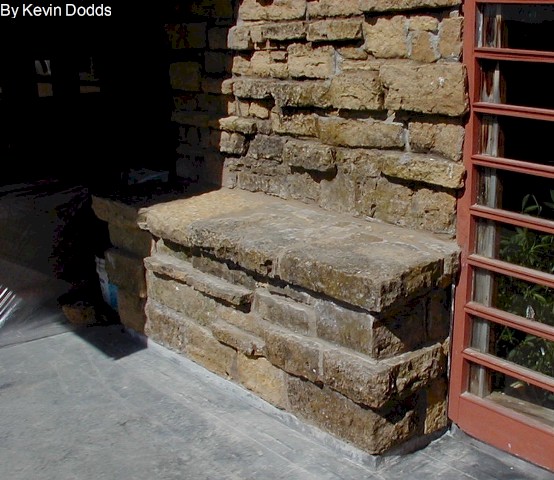

When they finished their restoration work and removed the closet, they let some staff members in to see the space:

I took this photograph in 2018. The four people stand in the background, to the right of the doorway and against the wall, stand where the Preservation Crew has removed the closet.

Success in doing this (attending to those little things in the back of my mind) is one of the things that gave me the courage to explore and pursue what may have looked, from the outside, like a waste of time.

First published December 31, 2021.

The photograph at the top of this post is the property of: The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York). The photographer is unknown.